Read 01a 관련

ARM Powered Product Showcase

| Motorola XOOM |  | | Itron OpenWay CENTRON Smart Meter |

| | Itron OpenWay CENTRON Smart Meter |  | | CompuLab Trim-Slice |

| | CompuLab Trim-Slice |  | | Blackberry Playbook |

| | Blackberry Playbook |  | | Innodigital WebTube HD Set-Top-Box |

| | Innodigital WebTube HD Set-Top-Box |  | | Olivetti OliPad 100 |

| | Olivetti OliPad 100 |  | | Hercules eCAFE Slim HD |

| | Hercules eCAFE Slim HD |  | | VINCI Tab |

| | VINCI Tab |  | | Tonium Pacemaker “Pocket-size DJ System” |

| | Tonium Pacemaker “Pocket-size DJ System” |  | | Magellan eXplorist Pro 10 GPS Navigation Device |

| | Magellan eXplorist Pro 10 GPS Navigation Device |  |

|

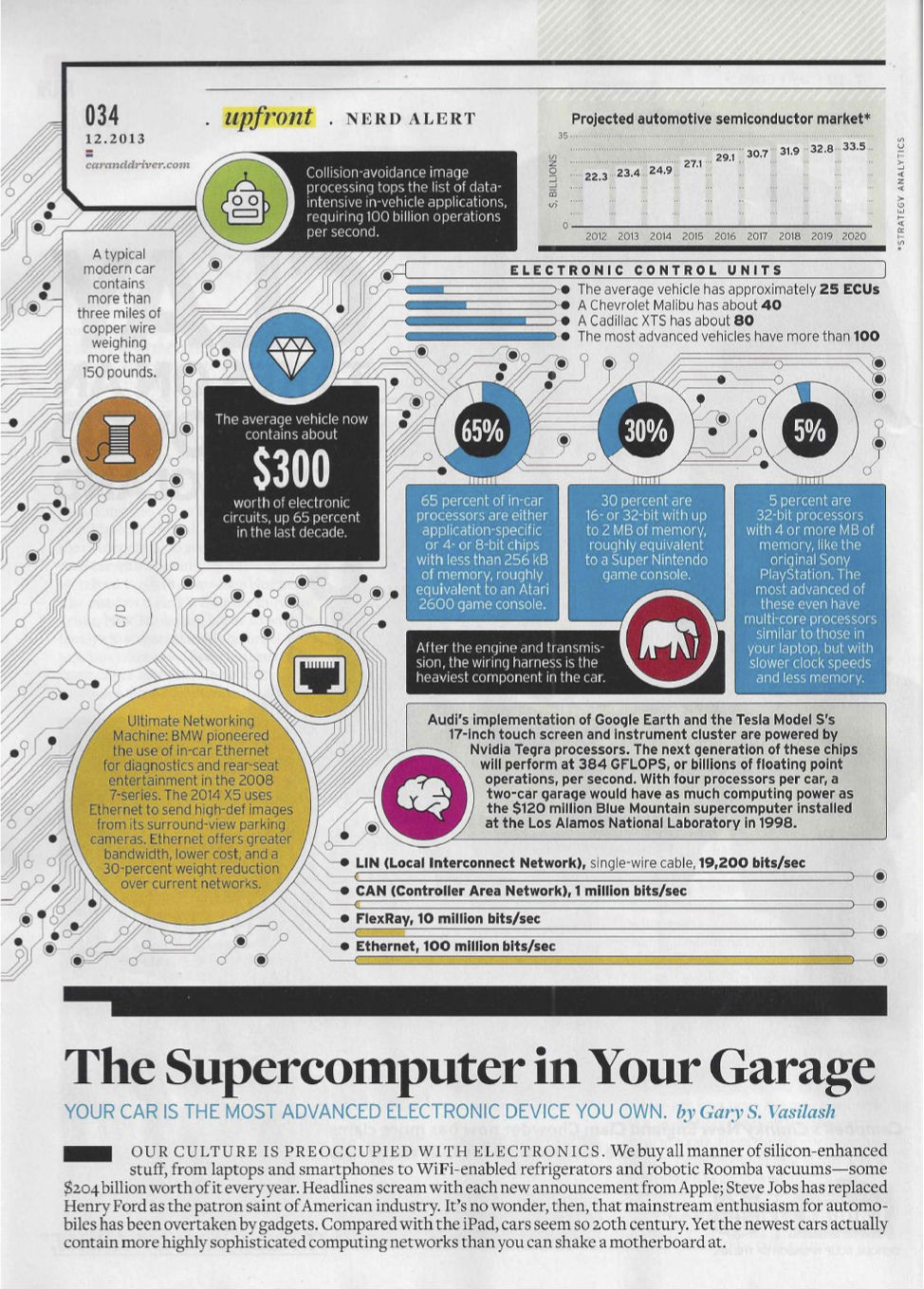

Infographics: Supercomputer in Your Garage

ExtremeTech - Embedded Processors

ExtremeTech - Embedded Processors

Embedded Processors, Part One

Intel's Pentium has almost 0% market share. Zip. Zilch. Yup, Pentium is a statistically insignificant chip with tiny sales.

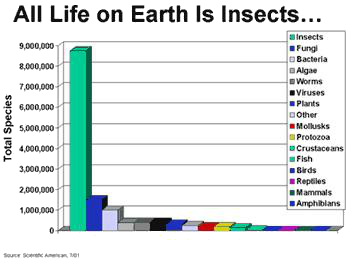

Surprised? Try this: all life on earth is really just insects. Statistically speaking, that's the deal. There are more different species of insects than of all other forms of life put together - by a lot. If you round off the fractions, there are no trees, no bacteria, no fish, viruses, mollusks, birds, plants or mammals of any kind. If you need help feeling humble, mammals make up just 0.03% of the total number of species on the planet.

Everything you know is wrong. Even about microprocessor chips.

What's this got to do with extreme processor technology? The comparison between Pentium and paramecia is a pretty close one. Ask a friend what's the most popular microprocessor chip in the world. Chances are they'll answer "Pentium." The newspapers constantly shout Intel's 92% market share, or some such number. Clearly, the Pentium is the overwhelmingly dominant species and all other chips are struggling for that last 8%, right?

Sorry, but thank you for playing. The fact is, Pentium accounts for only about 2% of the microprocessors sold around the world. Pentium is to microprocessors what viruses are to life on earth. No, that's too generous. Pentium volume ranks a little below viruses but a little above mollusks (i.e., snails) on the microprocessor food chain. The insects—the overwhelmingly dominant species—are the embedded microprocessors. They're the forgotten phylum that controls (approximately) 100% of the microprocessor kingdom.

With that potentially enlightening introduction, we welcome you to this first segment of a three part series covering the embedded processor space. We'll begin by reviewing usages and markets for embedded processors, and then cover the major chip families from the leading embedded processor vendors.

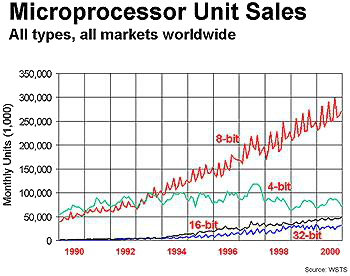

As you can see in the following chart, the volume of 8-bit embedded chips is enormous and growing steadily. These little suckers are selling to the tune of more than a quarter of a billion chips every month! That's one new 8-bit microprocessor for every man, woman, and child living in the United States, every month. Are you consuming your fair share?

You probably are without realizing it. We estimate the average middle-class American household has about 40 to 50 microprocessors in it - plus another 10 processors for every PC (more on that later). There's a microprocessor in your microwave oven and in the washer, dryer, and dishwasher. Another processor lurks inside your color TV and yet another one in the remote control. Your VCR (and its remote) has a processor embedded inside, as does your stereo receiver, CD player, DVD player, and tape deck. An automatic garage door opener (and each remote control for it) also contains a microprocessor. The average new car has a dozen microprocessors in it. If you have a 7-series BMW, congratulations are in order: you have 63 microprocessors in your new car. Don't feel too proud, though. The Mercedes S-class has 65.

What could all these "mobile processors" be doing? Well, every modern car has electronic ignition timing to replace the distributor, points, and condenser. Most Ford vehicles, including Jaguars and Volvos, use a PowerPC to control the engine. The PowerPC 505 processor was designed in the mid-1990s and includes one of the best floating-point units (FPU) available at that time. (Automotive designers are notoriously conservative about electronics, which is why the processor seems comparatively old.) The FPU helps the PowerPC calculate time-angle ratios, which is vital for valve and ignition timing. At the time the PowerPC 505 was introduced, it was comparable to the chips Apple was using in the Macintosh, but sells for just a few dollars.

Outside of the engine, automatic transmissions are microprocessor controlled as well. Newer cars even have adaptive shifting algorithms, modifying shift points based on road conditions, weather, and the driver's individual habits. Some systems even retain driver preferences and idiosyncrasies in nonvolatile memory. Antilock brakes generally also are computer controlled, replacing the hydraulic-only systems of earlier years.

Got a Volvo? The processor in its automatic transmission communicates with the processors behind each side-view mirror. Why? So the outside mirrors can automatically tilt down and inward whenever you put car into reverse gear, the better to see the back end of the car. It's also common for the processor in the car radio (or in-dash CD player) to communicate with the processor(s) controlling the antilock brakes. This way, the audio volume can adjust to compensate for road noise, and the ABS provides the most accurate information about road speed. High-end cars connect the processors controlling the airbags with those in the GPS and built-in cell phone. If the car's in a serious accident that pops the airbags, it will phone for emergency aid and report the exact location of the accident using the GPS. Eerie.

Processors in Video Games

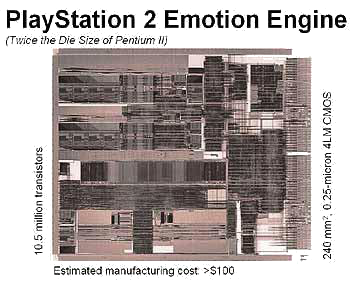

Obviously, video games such as the PlayStation, Dreamcast, GameCube, and N64 all have processors, and usually more than one. Each Nintendo 64 is based on a 32-bit MIPS processor, as is the original PlayStation. Nintendo switched to PowerPC for GameCube, while Sony stuck with MIPS for PlayStation 2, but designed its own custom version (the Emotion Engine) in cooperation with MIPS Technologies and Toshiba. The PS2 even includes a chip that clones the older PlayStation processor for backward compatibility.

The late, great Sega Saturn had four (count 'em) different 32-bit microprocessors inside. Three were from Hitachi's SuperH line with one Motorola 68000 just to baby sit the CD-ROM drive. Ironically, that processing power probably led to Saturn's downfall and Sega's eventual departure from the console market. Game programmers found that writing code for four processors was just too complicated. With a finite amount of time to get a game to market, programmers tended to cut corners and write games that used only one or two of Saturn's processors, making the games less appealing than they might have been. Symmetric multiprocessing is nontrivial, even in games.

The Additional Processors in Your PC

But what's this about ten microprocessors in a PC? Even the most avid over-clocker still has only one processor, right? One main processor, yes. But your PC has far more than just the single CPU from AMD, Transmeta, or Intel driving it. There's an 8-bit processor (probably a Philips or Intel 8048) in your keyboard, another processor in your mouse, a CPU in each hard disk drive and floppy drive, one in your CD-ROM, a big one in your graphics accelerator, a CPU buried in your USB interface, another processor handling your NIC, and so on. Except for graphics chips, most of these little helpers are 8-bit processors sourced by any number of Japanese, American, or European companies. Even the first IBM PC/XT included about a half-dozen different processor chips in addition to the 8088 CPU.

If you were the kind of über-nerd who fiddled with the BIOS of your first PC back in the day, you might remember playing around with keyboard scan codes. These are the funny two-byte codes sent from every PC-compatible keyboard to the motherboard. You got one scan code when pressing a key and another scan code when you released the key. Early PC games made use of these all the time. Well, those scan codes aren't generated automatically; there's no special mechanical switches inside your keyboard that emit ASCII bytes. There's an 8048 microprocessor (or a clone) in your keyboard that laboriously polls all the keys and sends a byte down the cable every time something moves up or down. The same little processor also lights the LEDs on your keyboard at appropriate moments. That's why your keyboard LEDs sometimes keep working even when Windows is locked up solid.

With so many different processors on the market at one time, it's tempting to wonder who the winners and losers will be. Who will be the dominant CPU player—the Intel Pentium—of the embedded market? When is the shakeout coming?

There is no shakeout coming. There are lots of embedded processors on the market because there needs to be a lot of embedded processors on the market. Intel dominates the desktop only because all computers are more or less the same. One processor can serve them all. That's not true of embedded systems at all. No, the number of different embedded processors is growing, not shrinking.

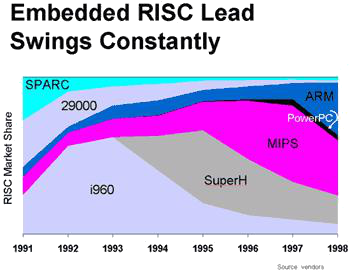

Lots of today's embedded microprocessors started out as high-end computer processors that didn't make it. MIPS, 68K, SPARC, ARM, PowerPC—they're all failed desktop processors that have wound up as embedded processors by default. None of these popular chip families started out as embedded processors. Their marketing managers never intended them to be used in video games, network switches, or pagers. No, they all had far more grandiose plans for their little children, as we'll discuss shortly. But even with such grand plans, notice the figure below depicts dominance is fleeting in the embedded business. It highlights a decade worth of embedded-RISC market share (the CISC-based 68K embedded processors are not shown, nor are any embedded CISC-based x86 family components) and how frequently—and rapidly—the lead changes.

In the very early 1990s, SPARC was a big winner primarily because it was one of the few RISC processors even available for embedded use. Sun was an early pioneer in promoting its high-end workstation processor for embedded use. The company still does license and promote embedded SPARC processors, but its early lead rapidly eroded as other companies entered the market.

We'll look more closely at many of the popular embedded chip families in subsequent pages.

Motorola's 68000 (68K) family is the old man of the embedded processor market, and the most popular 32-bit processor family in the world until just a few years ago. Sun originally used 68K processors in its first workstations, and all Macintoshes were 68K-based until PowerPC came along. Now 68K chips are almost always used for embedded systems, and Motorola still sells to the tune of about 75 million chips per year.

The whole 68K family is an example of CISC architecture that fell out of favor in PCs long ago, but still has some strong advantages for embedded usages. All 68K chips are binary compatible, and they have some of the best software development and debug tools found anywhere. Even though the 68060 processor topped out at a pathetic 75 MHz in 1994, the whole 68K family still goes strong, mostly because designers love it, and because so many of the chips are already designed-in to millions of existing products.

x86 Overview

The "x86 family" refers to Intel's architecture that started with the 8086 (Thanks to forum member JPMorgan for the correction from our previous indication that it was the 8080 — we agree, though some loosely consider the 8080/8085 as the real beginning of the x86 family, since the 8086 tried to maintain a certain degree of compatibility), through the '286, '386, and '486, and continues to this day with Pentium 4 and AMD's Athlon, and is even extended to include a 64-bit mode in AMD's upcoming Hammer. We all know that x86 processors dominate PC systems. But in embedded sales, x86 chips like the '486DX rank a distant fifth in sales behind the ARM, 68K, MIPS, and SuperH. That doesn't make them unsuccessful—there are more than a dozen competitors that rank even lower—but it's far from dominance.

Like the 68K family, the x86 family is an example of CISC architecture. It is one of the longest- lived CPU designs ever. Today's Pentium 4 can still run 8086/8088 software unmodified. That's both good news and bad news. The good news is that all x86-family chips are compatible, which is, of course, why we keep buying them for our PCs. The bad news is that the x86 is a miserable, old-fashioned, inefficient design that should have been scrapped long ago. In almost every measure, x86 chips are the slowest, most power-hungry, and hardest to program processors around. Almost anything would be better, and most of the alternatives are, which is why there's so much competition for embedded processors.

SPARC Overview

SPARC is best known as the processor used in Sun workstations, but it wasn't always that way. SPARC was one of the first RISC designs to see the light of day and also one of the first to be used in embedded applications outside of its original market. In the early 1990s, embedded SPARC chips were actually pretty common. Now they're almost nonexistent.

SPARC, like ARM and MIPS, is a licensed architecture. Sun doesn't actually make processors, so don't go looking for chips with the Sun brand name on them. A few years ago there were close to ten companies making SPARC processors, all different. Sun was really the only big customers for them, though, so almost all of the SPARC makers went out of business. TI and Fujitsu are the only significant SPARC chip developers left, and this early pioneering architecture has all but disappeared from the embedded scene.

Similar to SPARC chips in the past, AMD's 29000 processors (remember them?) were also popular, particularly in the first Apple laser printers and in some networking equipment. The 29K was an exceptionally elegant, high-performance RISC design. It was most notable for its whopping 192 programmable registers (most RISC chips have 32; Pentium has eight), which made it a programmer's delight. Alas, despite all of the 29K's architectural elegance, it was not long for this world.

Death came at AMD's own hand. Despite years of multimillion-unit sales, AMD simply pulled the plug on the entire 29K family in 1995. Why would AMD abandon an entire product line just as it becomes the second-best-selling RISC architecture in the world? Because its support costs were too high. This sad story underlines just one of the crushing costs associated with developing, supporting, and selling a successful microprocessor. In AMD's case, the 29K was selling well but the company had to pour all of its profit, and then some, into software subsidies. AMD was paying third-party developers of compilers, operating systems, and other programming tools to support the 29K. Such subsidies are typical. Software companies won't arbitrarily develop complex compilers or operating systems unless they know there's a lucrative market for such products—or unless they're paid up front. In AMD's case, these yearly subsidies were eating up all of the 29K's profits. Paradoxically, the world's second-most-popular RISC architecture was losing money.

As word of the 29K's demise spread, customers started looking for alternatives. Even though several 29K chips remained in production for a few more years, the writing was on the wall and customers fled to a number of other alternatives, including Intel's i960 family.

Intel i960 Overview

The i960 was once the best-selling RISC architecture on the planet, bar none. It was a terrific bar bet: ask any Sun employee to name the most popular RISC chip in the world and you were guaranteed a free drink. In the early '90s you could find an i960 processor in most every laser printer or network router made. The i960 was particularly popular in HP's LaserJet series of printers, just as LaserJet sales took off.

The i960 actually got off to an inauspicious start. Like most embedded chips, and all RISC processors, it was originally designed to power workstations. In this case, the chip came out of a joint venture between Intel and Siemens called BiiN. BiiN was supposed to develop fault-tolerant Unix workstations that competed with Sun, Apollo, MIPS, and others at the time. Alas, the market for fault-tolerant Unix workstations was approximately nil, so the two partners parted way and BiiN was no more. RiiP.

As with most divorces, the spoils were not divided evenly. Intel gained control of the processor it developed with Siemens and Siemens got… not very much. In fairness, Siemens may not have wanted the processor very much. It was expensive, slow, and very power-hungry. The processor was also festooned with complex fault-tolerant features that made it difficult to manufacture and debug and that had no (apparent) use outside of the workstation market.

Congratulations to Intel for turning a sow's ear into a silk purse. This cast-off processor, now called the 80960 or i960, rapidly found a home in embedded systems. The chip's fault-tolerant features were simply never mentioned in Intel's promotional literature and customers were left to wonder why the chip was so big and had so many pins labeled "no connect." Over the years, Intel eventually excised most of the superfluous features, trimming later i960 chips down to size.

The i960 family never did overcome its power-hog reputation, though, nor did later chips get much faster or much cheaper. By the mid-1990s the i960 line could be relied on to deliver the worst price/performance ratio of any 32-bit processor—including the miserable x86. Once again hoping to pull a rabbit out of its hat, Intel devised a new market for the i960: intelligent I/O controllers. The I2O standard was born, and it cleverly defined requirements that just happened to match the characteristics of existing i960 chips. After some initial lukewarm success, I2O controllers, and the i960 processors, eventually faded away.

MIPS, ARM, SuperH, and PowerPC Overviews

MIPS is a prime example of a high-end computer architecture that is more successful in toys and games than it ever was in engineering workstations. MIPS Computer Systems (which got its name from "microprocessor without interlocked pipeline stages") was originally a competitor to Sun, HP, Apollo, and even Cray. MIPS, the company, was acquired by Silicon Graphics (SGI) in the 1990s and SGI immediately started using MIPS processors in all its workstations. Before long, MIPS had a reputation for powering the highest end of high-end workstations.

Sadly, SGI found the workstation business was tougher than anticipated. Weakening profits from workstations couldn't support the awesome cost of developing new 32-bit and 64-bit microprocessors. Conveniently, at about the same time, MIPS/SGI signed up an unusual new customer: Nintendo. The Japanese game maker wanted to use a slightly modified MIPS processor in its upcoming N64 video game. This turned out to be MIPS' biggest deal ever—the company got two-thirds of its money from Nintendo throughout the late 1990s. Ultimately, SGI spun off MIPS as an independent company (again).

Although MIPS doesn't dominate the home video-game market like it once did, the architecture has comfortably settled into the number two RISC position. MIPS has extended its eponymous family of processors both at the high end, with its monstrous 64-bit 20Kc family, and at the low end, with SmartMIPS, a minimal 32-bit design for smart cards and other ultra-low-power systems. There's probably no other CPU family that reaches so high and so low while remaining software compatible throughout the line.

ARM Overview

ARM (formerly Advanced RISC Machines) also started out as a computer processor, but ultimately failed in that market, too. Now ARM is one of the most popular 32-bit embedded designs around. The English company was originally called Acorn, and its older BBC Micro computer was the British equivalent to America's Apple II or Commodore 64. The BBC Micro was probably the first commercial deployment of RISC technology, and many a British computer hobbyist learned the trade on a home-built BBC Micro computer with an ARM processor.

Editor's Note: We want to thank forum member Graham (Hattig) for pointing out the Acorn Archimedes, a follow-on to their BBC Micro, was actually the first to use an ARM processor — the BBC Micro used a 6502. Thanks Graham.

Apple, IBM, Commodore, and other early computer vendors ultimately overwhelmed the BBC Micro, but its processor design lived on. In recent years, the ARM architecture has challenged for, and then overtaken, the RISC lead. ARM's biggest volume wins have been in a number of digital cell phones, particularly those manufactured in Europe (ARM is the only European entry in this race). ARM's simple design gives it small silicon footprint, which, in turn, gives it modest power consumption. Its comparatively low power combined with its ability to be embedded into high- volume ASICs gave ARM a leg up in mobile phones.

Just as ARM seemed about to run out of gas, Digital Semiconductor (part of DEC) surprised the world with a technical tour de force: StrongARM. Using the same silicon technology it used with its phenomenal Alpha processors, Digital more than quadrupled the best speed anyone had seen in an ARM-based chip. Unfortunately, about that same time, Digital suicidally chose to sue Intel over an unrelated patent infringement. Intel settled the case quickly - by buying Digital Semiconductor lock, stock, and barrel, including the rights to StrongARM.

StrongARM now lives on under the new name of XScale (heaven forbid that Intel use the name of another processor company). The first XScale chips are part of Intel's new "Personal Internet Client Architecture" (PCA) and promise to maintain the high standards set by the late lamented Digital Semiconductor.

SuperH Overview

Hitachi's SuperH, or SH, processors have been around for more than a decade but they were almost unknown outside of Japan until recently. The SuperH family of chips includes some 16-bit and some 32-bit processors, most with added peripheral I/O and special-purpose controllers. SuperH's big hit was with the Sega Saturn video game, followed by the Sega Dreamcast. You'll also find SuperH chips in some of the handheld Windows CE computers from Compaq and Casio. The SH7750 processor was designed especially for Sega and includes some fantastic 3D geometry instructions that outstrip anything an x86 processor can do. The SH7750's features may not be as general-purpose as those in 3DNow!, SSE, or even MMX, but if you're rendering objects in simulated 3D space, SuperH has got you covered.

PowerPC Overview

PowerPC started squeaking into the embedded scene around 1996. Within two years, there were more PowerPC chips being sold in embedded applications than in computers (such as Macintosh), making PowerPC "officially" an embedded processor that just happened to also be used in a few computers. Even so, PowerPC remains a marginal player in the overall embedded landscape, selling more than SPARC but less than most 32-bit competitors.

The list of vendors above is by no means complete. We could fill another article on the other choices available just among 32-bit embedded processors. There are more than 115 different 32- bit embedded chips in production right now, all of them with happy, healthy users who love them. History shows that no company holds the lead for long in the embedded market. Maybe in a few years one of these players will be sitting at the top of the heap.

- Lexra: this Boston company started off selling a pretty good clone of the MIPS processor family but has since branched out into network processors with its NetVortex product line.

- PicoTurbo: like Lexra, PicoTurbo first made its name cloning ARM processors. Legal troubles and technical limitation led to branch out into other 32-bit applications.

- Improv: this company's Jazz processor is insanely complex and terrifyingly powerful. Both the hardware and the software are user-configurable and the chips are highly parallel. Not for the faint-hearted.

- Cradle Technologies: Another ambitious design, the universal microsystem (UMS) is a completely programmable chip that seems like it can do a million things at once.

- ARC Cores: this is the first company to invent a user-configurable microprocessor: a 32- bit design where you get to decide what instructions hardware features it supports. It's like Lego blocks for CPUs.

- NEC: in addition to being a MIPS manufacturer, NEC sells its own V800 family of 32-bit processors that are popular in disk drives and other deeply embedded applications.

- Tensilica: this company's Xtensa processor is also user-configurable, with options for shifters, arithmetic, and bit-twiddling.

- Elixent: what ARC Cores did for RISC processors, Elixent is doing for DSPs. This user- configurable design can replace several different processors with one that changes its stripes on the fly.

- Zilog: remember these guys? In addition to the venerable Z-80, Zilog has 16-bit and 32- bit processors as well as DSPs. None of them is particularly well known but they keep selling as long as Zilog is around to make 'em.

- PTSC: this San Diego company has a stack-based processor that's good for Java or anywhere code density is a prime concern.

- Xilinx: the FPGA giant now has its own processor family, MicroBlaze. You can only get it as part of a Xilinx logic chip but for many users that's just fine.

- Altera: another soft-processor alternative. NIOS is an Altera-only design embedded into a number of the company's programmable-logic chips.

- VAutomation: with AMD and Intel both out of the low-end 286- and 386-based embedded x86 business, this may be your best source for 286- and 386-compatible processors. VAutomation also has its own V8 RISC processor.

- Transitive Technologies: not really a CPU company, but a software firm that thinks they've cracked the problem of emulating other chips. With Transitive's code you can run MIPS software on a PC, or vice versa. The possibilities are endless and mostly weird.

- And the list goes on…

That concludes the first segment of our three-part series. Next, we'll cover embedded processor benchmarking, custom embedded processors, Java chips, and key embedded processor features that allow them to be so useful in numerous embedded applications.

Embedded Processors, Part Two

In [Part One] we provided an overview of the embedded processor market and reviewed the key players and their products. In this segment, we'll drill deeper into variations on the embedded theme, such as Java chips and various types of custom embedded processors. We'll also look at unique microarchitectural features and programming constructs that differentiate embedded processors from mainstream CPUs. Finally, we'll cover some methods of measuring embedded processor performance, which is no easy feat.

Java Chips

One class of processor that seems perpetually just over the horizon is Java chips. These are (or were planned to be) specially designed processors that executed Java bytecode natively, without an interpreter or compiler. Apart from being spectacularly ironic (the whole point of Java was to be CPU independent!), it's also stupendously difficult. Java runs poorly on all of today's microprocessors. This isn't because the good Java processors aren't here yet. It's because Java is innately difficult to run, regardless of what hardware it runs on. So far, Java has heroically resisted all attempts to improve its performance.

Not that many haven't tried. Sun itself, the original percolator of Java, proposed but then abandoned plans for a whole series of Java processors. MicroJava, PicoJava, and UltraJava were announced around 1998, with first silicon expected by 1999. Apart from a few sample prototypes, nothing ever came of the MicroJava 701, the first chip in the planned series. Sun then tried licensing PicoJava to a handful of Japanese vendors, but again nothing came of it. UltraJava never even got off the drawing board.

There's also been plenty of activity outside Sun. PTSC, Nazomi Communications (originally named Jedi Technology), and others have all toyed with hardware acceleration for Java. PTSC's Ignite-1 processor did a good job of accelerating the easy parts of Java. It's stack-based, like Java itself (and like HP calculators), so fundamental functions work smoothly and efficiently. But where all processors fall short is in accelerating the difficult parts of Java, such as garbage collection and task threading. It is precisely these sorts of functions that give Java its portability and power, and that also make it practically impossible to function entirely in hardware.

Java Accelerators

In the end, every company has retreated from the goal of an "all-Java" processor and fallen back on providing "hardware assists" for Java, while leaving the complex and awkward functions to software. As accelerators, these work fine. Just don't assume that they really run Java bytecode natively. Six examples of these accelerators are provided in the following table.

ARM's Jazelle bolts onto a special ARM9 core, so this has the advantage of being ARM compatible, if that's interesting to you. On the downside, Jazelle uses some of the ARM processor's resources in handling Java, so performance on normal (non-Java) code will suffer. Nazomi's Jstar is similar in concept: it's a coprocessor for an existing processor. One advantage of Nazomi is that its accelerators can theoretically work with any processor, although MIPS is the only one it currently supports. InSilicon's JVXtreme is much the same— it can be used in tandem with most other CPUs. Its small size makes it cheap to manufacture in volume, but also limits its performance because there's not much hardware there to provide an assist.

MachStream from Parthus promises better performance than any of the above coprocessors, but you pay for it in larger circuit size and increased memory usage. Both DeCaf (from Aurora VLSI) and Xpresso (from Zucatto) are closer to being standalone processors, although they can be used as coprocessors if you wish. Because both can be used standalone, they're pretty big as these things go. On the other hand, both promise better performance than their more lightweight competitors.

This is probably about as far as Java processors will go. Some very bright minds have looked at the problem and there's just not much more help that hardware can give. Java was invented to be hardware independent, and it looks as though it's succeeded.

If you yell "embedded processor" in a crowded theater, some people will think of processor chips soldered onto printed circuit boards, while others will think of "soft cores" designed into custom chips, and the rest will think you're a lunatic. All three groups of people are correct, but the days of buying processor chips off the truck are slowly disappearing as more people sink processors into their own ASICs (Application-Specific Integrated Circuits).

Ten years ago, designing a custom gate array or ASIC was a big deal. If you were one of the lucky engineers assigned to the project, it was a prestige job. Nowadays, designing a custom chip is pretty common. It's not exactly kitchen table casual, but it's certainly easier and less intimidating than before. Today's EDA (Electronic Design Automation) tools have brought chip design within the reach of most companies. The genie is out of the bottle.

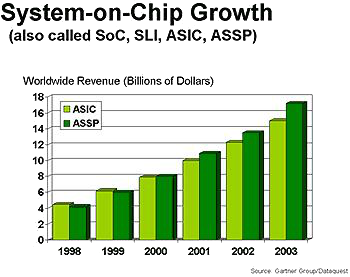

These numbers from Gartner/Dataquest show that sales of custom- or customer-designed chips has been growing steadily for the past few years. Note that the chart is titled System-on-Chip Growth. System-on-Chips, or SoCs, are custom chips implemented with ASIC/ASSP design techniques. SOCs incorporate numerous logic functions onto a single chip, instead of requiring multiple discrete components on a larger and more expensive printed circuit board. Expectations are that this market will continue to grow nicely. This chart makes a distinction between ASIC chips and ASSP chips (Application-Specific Standard Product) — an ASIC is designed by one company for its own use, while an ASSP is designed for sale to a narrowly defined segment of customers. The difference is only in semantics and the sales channel— the technology is exactly the same.

At over $20 billion per year in 2002, this is no small market! Furthermore, these numbers count only chips that have one or more internal, or embedded custom processors. That's $20 billion in processor-based chips that didn't come from a traditional microprocessor maker like Motorola, Fujitsu, or Intel. Instead, these were licensed CPUs – the recipe for a microprocessor.

In the past few years, licensing CPUs instead of selling chips has become the hot business model. Why make chips when you can sell the recipe? Chip factories (foundries) cost over a billion dollars, but licensing costs almost nothing because you don't actually make physical chips. Technology licensing has been compared to the world's oldest profession: you sell it, but you've still got it to sell to someone else, over and over.

And, indeed, this business is not new. Examples are Dolby Labs and Adobe, both of which license their technology (for noise-reduction and PostScript, respectively) to a number of product makers. You can't buy Dolby stereo equipment or Adobe laser printers, but their technology, and sometimes their logo, is in the product.

Processor licensing takes this one step further. Instead of making and selling physical CPU chips, some companies license their CPU design to manufacturers instead. This has advantages for both sides: the licensing company doesn't have to invest a billion dollars in a semiconductor foundry, and the licensee has the freedom (albeit limited) to manufacture the chips when and how they please. It's the difference between being an architect and being a building contractor.

All of today's processor companies fall squarely into one category or the other. They're either architects licensing their designs, or they're contractors building and selling real chips. The latter category is shrinking while the former one is growing. Intel, Motorola, Texas Instruments and most of the other "old economy" chip companies are chip manufacturers that do not offer their designs for license to outsiders.

Younger companies like ARM, MIPS, ARC Cores, and PicoTurbo are in the other category: they don't make chips – never had, never will. Instead, they turn over their "core" designs to companies that will make chips, for a fee. Rambus uses a similar business model, though obviously for its DRAM interface, not processors. Companies like VAutomation, inSilicon, Parthus, Tality, and Syopsys also license IP for other "components" such as USB, Ethernet, timers, DMA, and MPEG controllers, among many others.

If you're designing a custom ASIC, using a licensed microprocessor makes all the sense in the world. You can put the processor inside your ASIC instead of beside it. A licensed processor gives you access to existing software, operating systems, compilers, middleware, applications code, emulators, and so on.

A big benefit to embedding a licensed CPU is that you can build your chip your way. Before ASIC cores, you had to settle for the package, speed, power consumption, and price that your CPU vendor set. If that chip was discontinued, you were out of luck. If the chip was too slow and the vendor didn't offer a faster one, you lost out again. A licensed core provides at least a little bit of control over your own destiny.

One complaint about CPU licensing has been the cost. A few years ago, ARM and MIPS used to charge more than a million dollars for a license. For your money, you got access to one generation of the processor architecture, such as the ARM7 or the MIPS R4200. Subsequent generations cost extra. You also had to pay royalties for each chip that used the CPU core. Royalty rates vary, but figure on about $0.35 to $2.00 per chip, with the cheaper rates available only after you've shipped hundred of thousands (or maybe millions) of units. Not an inexpensive undertaking.

Those prices have come way down. ARM and MIPS are generally still expensive but some newer companies license 32-bit cores for $250,000 or so. Simpler 8-bit and 16-bit cores can be had for under $75,000. Royalties seem to be holding steady though, at anywhere from $0.25 to $2.00 per chip.

Embedded CPU cores have enabled a whole wave of new products. Would Nokia really be able to fit a separate processor chip into their tiny cellular telephones? For today's smaller, battery- powered devices there is no alternative to designing a custom ASIC, and that means licensing a processor core.

Actually, it often means licensing more than one. According to Gartner/Dataquest, intelligent ASICs already average 3.2 processors per chip, and the number is going up. It looks as though licensed CPUs are the wave of the future.

Next, we'll delve into some of the technical aspects of embedded processors, and what makes them so desirable to programmers and system designers.

What do Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum have to do with embedded processors? Not a lot really, but they help me introduce bit twiddling: the ability of some processors to handle individual bits in memory. Bit twiddling is a useful capability provided by some embedded processors.

By "bit twiddling" I mean bit manipulation—setting, inverting, testing, or clearing individual bits in a register or in memory. Most RISC processors can't do this, but most CISC chips can. Bit twiddling is fantastically helpful for encryption algorithms, for calculating checksums, for controlling peripheral hardware, and for most device drivers. There's lots of times where you'd like to check whether, say, bit 4 of a certain status register is set, or you'd like to invert bit 12 of some control register. Well, lots of times if you're an embedded programmer, that is.

To see the value of bit twiddling, let's consider the alternative. Say you're checking the status of an Ethernet controller chip to see if some new data has arrived. Most controller chips have a status register with a bit that goes high when a new packet has arrived. To check if, say, bit 4 has gone high yet you'd have to read the entire register (more likely, the entire 32 bits surrounding the register) at once. That action by itself may screw up the Ethernet controller; many peripheral chips refresh their status every time you read them, so touching unnecessary parts of the controller is destructive.

After you've gobbled the status bit (plus 31 other bits you don't care about) you'd need to mask off the other 31 bits with an AND instruction – assuming you've got the mask value already stored somewhere. Then you check the result against zero. As an alternative, you could shift the value you read by four bits to the right and check if you've got an even or an odd result (an odd results means bit 0 equals 1). Then you may or may not have to store the status bit back again; some controller chips like you to acknowledge that you've read the status correctly.

Or – and here's the good part – you could use a processor that can bit twiddle. The whole 68K family has a BTST (bit test) instruction that tells you whether any arbitrary bit anywhere in the world (okay, anywhere in your system) is either set or clear. If you want, you can use BCLR (bit test and clear) to test and then automatically reset the bit, all in one instruction. The BSET instruction does the opposite.

This is useful stuff if you're flipping bits in an encryption algorithm or a checksum, or testing densely packed data structures. It's also useful for finding the ends of data packets, which are often marked with a "stop bit." The list goes on.

Code density is an all-important factor that most PC users don't care about at all. Quite simply, "code density" measures how much memory a particular program written for a specific CPU consumes. This is a function of the chip, not the program. It's also called "memory footprint" and it varies quite a bit from one processor to another. For embedded programmers, this is a big deal. For Microsoft, it's obviously not.

If you're a programmer, you already know that the same C program might compile into a bit more or a bit less memory depending on the compiler, or on the optimization switches you use. But the memory footprint will also be affected by the choice of processor chip. The same C program compiled for a SPARC processor will probably be twice as big as the same program compiled for a 68030. This has nothing to do with the compiler, and there's nothing you can do to change it; it's an inherent characteristic of the SPARC and 68K processors themselves. Welcome to code density.

When you're writing code for a small, cheap embedded system like a cellular telephone, memory footprint is a huge deal. It's common for embedded products to be limited by their memory, not their performance. MP3 players are priced based on memory capacity. Squeezing that MP3 operating software into a little memory as possible is critical. Embedded programmers tend to rank their favorite processors based on code density instead of performance, power, or price.

How much difference does code density make? Well, ratios of 2:1 or bigger are pretty common. For instance, a SPARC processor will probably give you half the code density (twice the memory usage) of an x86 chip like a 386, 486, or Pentium. That's just the nature of these chips and there's nothing you or your compiler can do about it. The rule of thumb is that CISC processors (such as the x86 and 68K) have almost twice the code density of RISC processors (such as SPARC, ARM, MIPS, and PowerPC). Thus here's a case where CISC outshines RISC. If you're spending more on memory than on your processor, you could almost double your money by switching processors.

Within these categories, there is a lot of variation. For example, PowerPC chips generally have slightly better code density than SPARC chips. ARM is better than MIPS. SuperH is better than ARM. And so on. There's no official list or ranking because it depends so much on the particular program you're compiling. The numbers above are averages; your mileage may vary.

Where Does Code Density Come From?

One thing that gives RISC processors poor code density is the very thing that their name represents: reduced instruction sets. By definition, RISC chips support only the minimum number of instructions necessary to make a computer work. Anything that can be done in software is removed from the hardware. This makes for comparatively small and streamlined chips, but it bulks up code terribly. Many RISC chips can't do simple multiplication or division, so programmers get the thrill of recollecting their high school days and proving that multiplication is simply repeated addition. Likewise, integer division is usually synthesized from shift-right, mask, and subtraction operations.

RISC chips have lousy code density compared to their CISC cousins, but CISC instruction sets, in contract, have grown over time, adding features and instructions like a ship accumulating barnacles. Sometimes these additions aren't elegant or orthogonal but they get the job done. An example is Motorola's TBLS instruction, which appears on several chips in the 68300 family. It's an unusual instruction that's either totally worthless or worth any price, depending on what you're building. In brief, the TBLS (table lookup and interpolate) instruction figures out the missing values in a sparse table. You define the data points in an XY graph, and TBLS interpolates the missing value in between those points. It's tremendously useful for systems with nonlinear responses or that use nonlinear algorithms, such as motor control. The TBLS instruction is only 16 bits long and executes in a handful of cycles, but it replaces a mountain of if-then-else statements in a C program. And it's faster. Hooray for CISC.

Transferring stuff to and from memory seems like a sort of basic feature, doesn't it? Yet different processors do this in different ways, and it matters more than you might think. We're not talking about bandwidth or latency here. We're talking about alignment, and whether a processor is even capable of doing the task you want.

In the RISC view of the world (which is to say a workstation-centric point of view), everything in memory is neatly organized in nice even rows. Everything is arranged in 32-bit chunks and all the chunks are conveniently aligned in memory because the compiler put them there. This makes designing the chip easier (always a high priority for RISC) because when your memory is 32 bits wide and all the data is 32 bits wide, you can always grab a whole 32-bit chunk in one go.

Ah, but in the real world things aren't always so tidy. Particularly when you're dealing with network data or communications packets, where data storage can be messy. TCP/IP headers aren't 32 bits long, and checksums or CRCs can be odd lengths like 20 bits, or 56 bits. Video data is also peculiarly organized, and encryption keys are who-knows-how long. When you've got odd-sized data packed together, your nice, neat alignment goes out the window. Operands often "wrap around" a 32-bit memory boundary, starting at one address, but finishing at another. Even 32-bit quantities might be stored at odd-numbered addresses, forcing a wrap around the natural memory boundary. In a 32-bit system, odds are three-to-one against such unpredictable data falling on a natural 32-bit boundary.

Most RISC chips can't handle this situation at all. They are congenitally incapable of loading or storing anything other than 32 bits at a time — and those must be aligned on a 32-bit boundary.

Even if you're a hot-shot assembly language programmer, you simply cannot make a MIPS processor (for example) load a byte from an odd address. It's not in the instruction set.

Most older CISC processors, on the other hand, have no problem with this. The whole x86 family, from the earliest 8080 to the newest Athlon and Pentium 4, does this all the time. Yes, this is a case where x86 does shine. Motorola's 68K chips also eat unaligned data operands for breakfast.

The moral here is this: if you're designing a system that has to handle unaligned data, take a good look at the back of the datasheet for your processor. Nobody broadcasts the fact that they can't do unaligned loads and stores— you'll have to look closely at either the bus interface or the instruction set for clues. Without unaligned data transfers, you'll have to force all your data packets to be aligned somehow. Or come up with a software trick to split operands into neat chunks and store them on aligned addresses. Yuck.

No, this is not the WPA procedure to make your new copy of Windows XP run (polite groans, please). This is an unusual way that some processors manage their registers. Or manage to keep you away from them, really.

If you've done any programming before, you know that all CPUs have registers. Some have a lot — the late AMD 29000 had 129 registers — and some have just a few, like Pentium's pitiful eight general purpose registers. Generally speaking, the more registers, the merrier, because it gives you more space to store intermediate values and a bigger "workspace."

When you run out of registers, it's generally time to push stuff onto the stack or to store it as a variable in memory. Passing parameters (arguments) to a subroutine or object also uses either registers or the stack. Register windows attempt to fold these two techniques into one, to reduce memory overhead and speed up function calls. It works, kinda.

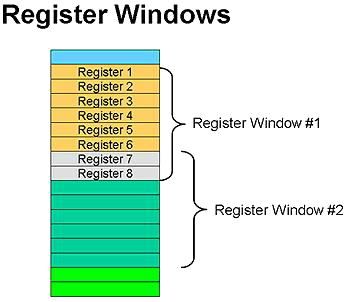

Note the figure below shows how a processor with register windows appears to the programmer. In this example, you've got eight registers that you can actually "see." This is your register window— the rest of the registers are invisible to your code and you can ignore them. Every time you call a subroutine, however, this window shifts slightly, covering up some of the registers you can see, while uncovering others. You always see only eight registers at a time — it's just not always the same eight registers.

Weird, huh? The idea behind this is to encourage you to pass parameters by using registers instead of the stack (which is much slower). In our example, the two register windows overlap by two registers. That is, the last two registers in one window are physically the same as the first two registers in the next window. The window shifted by six registers.

When the called function or subroutine starts, it already has two parameters loaded into its accessible registers. Voila! No need to push and pop stuff off the stack between function calls. At least, not unless you're passing more than two parameters. That's why most chips with register windows have variable overlaps. You get to specify how many registers are shared between parent and child tasks. More overlap gives you more room for parameter passing, but less room for general-purpose storage.

Register windows are most commonly associated with SPARC processors used in Sun's workstations, although Tensilica processors use register windows as well. In SPARC's case, the windows are circular; the last register window "wraps around" and overlaps the first window. In all, you get about eight complete windows. After that, you have to resort to using the stack like everyone else.

Register windows are a neat idea — so how come everyone doesn't use them? Well, my friends, because they're not really all that great. People have been studying computer science for decades and almost no one chooses register windows. Not because it's patented or anything, but just because there's hardware and software problems with it. On the hardware side, windowing the register file means designing in lots and lots of multiplexers. The chip has to make it appear as if any physical register could be any logical (programmer visible) register, and that requires a lot of wires, switches, and multiplexers. If you've noticed, SPARC processors are about the slowest RISC chips you can buy. That's partly because the hardware for register windows is so complex and hard to make work fast. Many CPU silicon designers in the 1990s complained bitterly about the rat's nest in the center of SPARC chips for that reason. Note that Intel's IA-64 processors have register frames, which are similar to SPARC's register windows, but they can be dynamically sized and are more flexible than the SPARC implementation. While the IA-64 design is interesting, we likely won't see many high-volume, low-cost IA-64 embedded designs for a long, long time.

The software problem is a bit more subtle. When your processor runs out of register windows it has to start pushing stuff onto the stack. That's all automatic, so don't worry about accidentally overwriting your registers. No, the problem is in predicting performance and finding bugs. Determining exactly where in a program you'll overflow the registers is nearly impossible, so estimating performance is tough. A random interrupt here or a particular parameter there might cause the windows to rotate one extra time, overflowing onto the stack. If you're concerned about deterministic performance, you can forget register windows. You'll also drive yourself mad trying to figure out why the exact same code runs faster 87% of the time and slower 13% of the time.

Code never runs in a straight line. Or if it does, you're not trying hard enough. Lots of studies show that about 15% or more of most programs are branches — which is kind of a shame, because branches don't actually do any real work. They're the skeleton on which we hang the real meat of the program. Branches are also bad because they waste a processor's time, and the faster the processor, the more time it wastes. That's because branches upset the train of thought going on inside a fast microprocessor. Programs are light freight trains— the more boxcars you've got moving the harder it is to suddenly sidetrack them.

In microprocessor terms, the boxcars are pipeline stages, but we'll refer you to ExtremeTech's story called "PC Processor Microarchitecture" for more details. As processors got faster their designers spent more and more time trying to figure out how to avoid branches. Their conclusion: you can't. So the next project became finding a way to predict the direction a branch will take. If the processor knows ahead of time where the branch will go, it's not really a branch anymore, is it? Their conclusion: you can't do that 100% of the time either. Bugger.

So that leaves us with trying to minimize the ill effects of branches through a number of bizarre and nefarious means. The simplest form of branch-damage-control is to do nothing at all. This is what most older processors, circa 1980 do. They simply assume the code will "fall through" all branches and blindly fetch code in a straight line. If the branch is taken, some amount of code is thrown away. This isn't a huge problem because older processors have short pipelines, so there's not much to undo (remember the boxcars?).

In a sense, older CISC processors like the early 68K and x86 chips assume that all branches will not be taken, by default. Mispredicted (that is, taken) branches cause the processor to flush its pipeline, find where the branch goes, and start over at that point. As I said, that's not a lot of damage when you're only moving at 33 MHz and have short pipelines.

The next step up the evolutionary ladder is static branch prediction. Static, because it's fixed in the code and can't change. In this case, there's really two forms of prediction for every branch instruction— branch (probably) and branch (probably not). PowerPC chips have this feature, and if you're a PowerPC programmer you can choose which form to use. PowerPC compilers do this on their own, based on some basic statistics. Branches that point backwards are very likely to be taken because they're probably at the bottom of a loop. Branches that point forward are iffy; they could go either way, so compilers usually assume they will not be taken. You can override this decision logic as a programmer, if you know something the compiler doesn't.

Next we get into dynamic prediction, which accomplishes in hardware what static prediction did with the compiler. Here, the chip itself makes a SWAG about the likelihood of branching. In its stupidest form, the processor might just assume backward, yes; forward, no. In reality it gets much sexier than this. Midrange embedded MIPS and SPARC chips keep one or two bits of history about the last few branches they encountered (these are called global history bits). These simple counters make use of temporal locality, the tendency of programs to branch frequently and in groups. If the last few branches were taken, the thinking goes that the next few are likely to be taken, too.

Local history bits are more advanced and record the taken/not taken history of individual branches, rather than lumping all branches together. Higher-end RISC processors and even the newer CISC processors often have this feature, but it's tricky to implement. You can't actually expect the chip to record the history of every branch in your program. How many should it plan for? Instead, these chips combine branch prediction with caching to produce a branch-history buffer, or BHB. This is a cache of taken/not taken history bits for as many different branches as the cache has room to hold… Like any cache, it's not perfect but it helps. It's possible that the BHB cache may thrash badly if two branches happen to fall on the same BHB cache line, or that one branch's history gets ousted by another branch, but that's the way these things go.

Beyond this, processors can get into all sorts of weird prediction mechanisms that include saturating counters, multiple global and local predictors, hashing algorithms, and even weighted combinations of all these. It's worth almost any amount of silicon to eke out more accurate predictions. For a fast processor, anything else would be a train wreck. As expected, you'll see a variety of branch prediction techniques across the various embedded processors.

Speaking of caches, most embedded processors have them by now. Some even have configurable or variable-sized caches. Yet not everyone really likes caches. Some programmers prefer not to have a cache in their system and may try to disable when if it's already built-in.

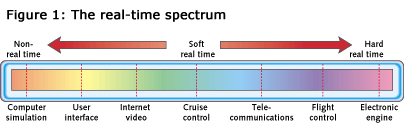

Why the occasional antagonism for caches? Because they are not deterministic. That is, caches lead to irregular and slightly unpredictable behavior. For some classes of embedded systems, predictability is important and anything that adds uncertainty — even if it improves performance — is a bad thing. Antilock brake systems, robot control, some laser printers, and many medical applications cannot use caches because it's too hard to prove that the system is reliable under all circumstances.

For the rest of us, caches are a boon. They take up some of the slack between processors (which get 4% faster every month, on average) and memories —which don't seem to get much faster at their fundamental core (versus interface) level at all. The caches on PC processors are kind of dull. They get bigger all the time, but they don't really change much. The caches on embedded chips, however, offer all kinds of options.

Cache Locking

One option is cache locking. This appeases the anti-cache contingent because it allows some or all of the contents of the cache to be locked in place, essentially tuning the cache into a glorified SRAM. Sometimes you can force certain data (or instructions) into the cache before locking it, in which case it really is an SRAM. Other times you take what you get, and locking the cache simply disables its normal replacement mechanism. Partial locking is also common, where one-half, say, of the cache operates normally while the other half is locked.

Write-Back Cache

Another big choice is write-back versus write-through caches. Write-back caches (also called copy-back caches) are most common in computer-type systems but not desirable in the more industrial embedded systems. When data is stored to a write-back cache, it only goes as far as the cache— the data is not written out to memory. This saves a lot of time, and minimizes bus traffic, but it has one drawback: the "memory" might have been waiting for that data.

Write-Through Cache

In lots of embedded systems there are peripherals, controllers, and hardware registers all over the memory space that need to be updated frequently. A write-back cache will intercept attempts to write to these devices, thinking it's helping by caching the data. That's why write-through caches are popular in many systems. As the name implies, write-through caches write the data "through" the cache to outside memory (or other hardware) as well as caching it. The process takes longer but guarantees that all write cycles really do get to where they're going.

Benchmarks are like sex: everyone wants it, everybody is sure they know how to do it, but nobody knows how to compare performance.

The key benchmark word seems to be MIPS, a term that's often bandied about incorrectly. That's understandable, because there are at least four definitions — MIPS is the name of a company, the name of a RISC architecture, and a measure of performance. The fourth definition, and what it really stands for, of course, is "meaningless indicator of performance for salesmen."

Time for today's history lesson, children. MIPS used to mean "millions of instructions per second" but it doesn't any more. (Note for the pedantic: There is no such thing as one MIP, it's one MIPS. Leaving off the S is like abbreviating miles per hour as MP. So there.) The first computer to reach this historic milestone was Digital Equipment Corp's VAX 11/870. In the rush to compare IBM, Sperry, and other big computers against the mighty VAX, marketers needed a program that could run on all. Enter Dhrystone, a synthetic benchmark originally written in PL/I that could be compiled and run on different makers' computer systems. (The name Dhrystone is a pun on the word whetstone, a sharpening stone for a knife and the name of another popular benchmark at the time.)

It so happened that the VAX 11/780 could run through 1,757 iterations of the Dhrystone program per second. The thinking was that if another computer could also score 1,757 Dhrystones per second, it was as fast as a VAX and, by implication, also a 1 MIPS machine. Suddenly, MIPS had ceased to measure instructions per second and instead came to mean "VAX equivalents."

The problem has been getting worse ever since. Dhrystone has been rewritten several times, in a number of different programming languages. The C version is most common today. More sinisterly, programmers found they could "improve" Dhrystone and speed it up considerably. Compiler writers also saw an opportunity to make the benchmark look better by "optimizing" Dhrystone in various ethically questionable ways. And, as always, some people flat-out cheated. Dhrystone now measures the performance of marketing departments, not microprocessors. It could be used to assign pay raises to PR professionals.

Quick! Call the EEMBC!

The light at the end of the benchmark tunnel comes from EEMBC, the Embedded Microprocessor Benchmark Consortium. EEMBC (pronounced "embassy") is an independent industry group of about two-dozen processor vendors, large and small. EEMBC's charter is to throw off the tyranny of Dhrystone and replace it with a collection of more useful cheat-proof benchmarks. EEMBC's first insight was that no single benchmark score could capture all the dimensions of performance that someone might want, so they didn't try. Instead, EEMBC provides a series of narrowly targeted benchmarks and allows members to pick and choose the ones relevant to the application at hand. For example, there are EEMBC benchmarks for motor control, network parsing, image rasterization, compression and decompression, and more. EEMBC scores are made public only after EEMBC has independently verified them. You can check out EEMBC at www.eembc.org.

That wraps up Part Two of our introduction to embedded processors, and in our last segment, we'll cover digital signal processors (DSPs), media processors, and power-saving tricks.

Embedded Processors, Part Three

In [Part One] and [Part Two] of this series we delivered an overview of the embedded processor market and key product families. We also looked at Java chips and other custom embedded processors. Then we reviewed some of the microarchitectural and programming features that differentiate embedded processors from mainstream CPUs. And we described some performance measurement techniques and issues. In this final segment, we'll dig into DSPs, media processors, and power saving techniques.

DSP Processors

What's a digital signal? Or, more to the point, what's a digital signal processor (DSP)? DSPs have burst onto the scene in the past few years, from obscurity to almost a household word. Texas Instruments now runs television ads touting "DSP technology" to an audience of football fans that has no idea what that means. To tell the truth, a lot of engineers and programmers don't know what DSPs are, either.

What's digital is the processor, not the signals it processes. DSPs are just another type of microprocessor, albeit ones with slightly odd instructions. Odd to computer weenies, anyway. They're meat and potatoes to mathematicians, sound engineers, and compression or encryption aficionados. Even at nerd parties, the DSP engineers and the CPU engineers don't talk to each other much. Both sides think the others are a bit strange.

DSPs aren't really all that different from CISC or RISC processors. They have registers and buses, they load and store stuff to memory, and they execute instructions generally one at a time. The most noticeable difference is in their instruction sets. DSPs tend to have lots of math-related instructions and relatively few logical operations, branches, and other "normal" instructions. DSPs are geared to perform intense mathematical calculations on a limited set of data, over and over. They're repetitive convolution engines. The "digital signal" parts comes from their use in processing radio, audio, and video data streams – which are inherently analog signals – after they've been converted to digital form. Think of DSPs as programmable analog circuitry.

The DSP market isn't as broad or wide as the general-purpose embedded microprocessor market. It's growing fast, but is served by about five big companies (plus a lot of new start-ups every week). Texas Instruments is the 500-pound gorilla in the DSP market, with Lucent, Analog Devices, and Motorola all battling for second place. Infineon, BOPS, 3DSP, Hitachi, ZSP/VLSI, Clarkspur, DSP Group, ARM, 3Soft, and even Intel all play around the fringes.

Over the last few years, DSPs have started to look more like regular CPUs (but not that much more) while CPUs have started to look more like DSPs (but not that much more). Both sides try to encroach on the other's territory and produce the "ultimate" processor that can handle both DSP and general-purpose processing tasks. Some of these are very popular, but the quest for the ultimate unified solution seems hopeless. RISC families like MIPS, ARM, and PowerPC have added DSP-like features, but this doesn't make them DSPs. Most start by adding a MAC (multiply-accumulate) instruction that helps some DSP inner loops. (Multiply-accumulate is a normal two-in, one-out multiply that adds the product to a running total; hence, "accumulate.") It's true that DSPs do a lot of multiply-accumulates, but that's not the whole story.

Bandwidth is what separates a lot of DSPs from the CPUs – the ability to gobble up and spit out lots of data, consistently, in an uninterrupted stream. Because DSPs are often used as a kind of programmable analog filter, they need to run continuously, without interruption, for long periods. That means they need to be reliable (no Windows 9x here) and they needs lots of bus bandwidth to shovel data from Point A to Point B. Lots of DSPs therefore have two data buses, X and Y, compared to the usual one for RISC and CISC processors.

Finally, DSPs aren't generally designed to work like microcontrollers, making lots of control-flow decisions or performing logical operations. This is why DSPs are often paired up with another processor that handles the "overhead" of the user interface, hardware control and other housekeeping chores, while the DSP concentrates on crunching numbers as fast as possible.

Media Processors

If you thought DSPs were weird, you haven't looked at media processors. These are a class of special-purpose embedded processors tweaked for processing pixels, colors, sounds, and motion. They're a bit like DSPs, a bit like normal CPUs, and a lot like nothing you've ever seen.

There are a lot of different media processors out there, though not as many as a few years ago. TriMedia, Equator's MAP, BOPS' ManArray, Silicon Magic's DVine, PACT's XPP, and even Sony's Emotion Engine chip in the PlayStation 2 are all examples of current media processors. Such chips tend to include functional units like variable-length coding engines, video scalers, and RAMDACs. Many media processors are used, or intended to be used, for high-definition digital television.

They also tend to be highly parallel, with many operations running at once as the chip separates the audio stream from the video, decompresses the audio, applies Dolby 5.1 processing, corrects errors in the bit stream, formats the video for the screen width, inserts the picture-in-picture from a second tuner or video source, and overlays the translucent channel guide over the image. Try that with your Intel P4 2.2GHz or Athlon XP 2000+ rig!

Another thing that sets embedded processors apart from their PC and workstation cousins is their lower power consumption. On average, embedded processors consume far less electricity than a PC processor, and that's not necessarily because they're slower or simpler chips. Power consumption is simply not a top priority to Intel or AMD when they're designing PC processors – sure they try to cut down power requirements on mobile processors, but resultant power utilization is still much higher than typical embedded processors. Power consumption (and the heat dissipation that goes with it) can be a very huge deal to some embedded customers.

Consider your cellular telephone. How useful would it be if the battery only lasted as long as the one in your laptop computer – about three hours? And how useful would it be if that battery were just as big and heavy as your laptop's? Palm Pilots run for months between battery charges; cell phones should last at least a day or two. Sparing the watts is big business in the embedded world.

"Consider your cellular telephone. How useful would it be if the battery only lasted as long as the one in your laptop computer – about three hours?"

Advanced Silicon Process

The single, most basic trick to lower power usage (but also the most expensive one) is to use a leading-edge silicon process to manufacture the chips. Contrary to popular opinion, embedded processors are not built on yesterday's cast-off 3.0-micron process by old ladies in hairnets with X-Acto knives. On the contrary, chips like Intel's XScale or the SmartMIPS family rely on cutting- edge silicon like that used for Athlon or Pentium 4.

Silicon is the most basic determinant of power consumption because of basic physics. The formula for power consumption, P=CV2f, says that power increases geometrically with voltage; the other terms (capacitance and frequency) have a linear effect. Chip designers can reduce the capacitance of their designs all they want, but nothing will lower power like lowering the voltage – and that means the latest semiconductor processes. XScale chips operate from as little as 0.65 volts; so do processor for smartcards. A 3.3-volt power supply is becoming unusual; 2.5-volt chips are more common. Pretty soon we'll be able to run 32-bit processors on bright sunlight or the current from two lemons and some copper wire.

Split Power Supplies

Split voltages are also showing up here and there. Building an entire system that runs on, say, 1.5 volts can be tough, so some processors have two different voltage inputs: a low-voltage source for the processor itself and a comparatively higher voltage (3.3 V, for instance) for the chip's bus interface and I/O pins. This allows a very low-voltage chip to still talk to commercially available memory and core logic. Digital's StrongARM was the first embedded processor to do this.

Static Logic Design

After voltage and silicon there's still lots of power-saving tricks embedded in embedded processors. Static operation is one. That's the ability to stop the clock dead and freeze the state of the CPU as if it was in suspended animation. It's like stopping someone's heart indefinitely and then starting it again as if nothing had happened. Obviously, this doesn't work well for people (superheroes excepted), nor does it work well for most microprocessors. Pentium, for example, loses its mind if its clock input ever goes away. Motorola's DragonBall (used in Palm and Handspring PDAs) is one example of dozens of different "static" processors that don't mind having their clocks stopped for a few microseconds or a few hours.

Clock Gating

Clock gating is another trick. This is a limited version of clock stopping that shuts off parts of the chip when they're not being used. CMOS logic transistors only consume power when they're wiggling, so shutting off the clock for a few moments can shave a few milliamps off the total energy bill. Processors can tell, based on the instructions they're executing, whether you'll be needing the MMU in the next few cycles. If not, why not shut it down for a while? Only half of the chip might actually be "on" at any given moment.

Frequency Scaling

Frequency scaling allows programmers to dial in the amount of power consumption (and performance) they want. Not many chips can do this yet, but it's increasing in popularity. You store a number in a special scaling register to speed up or slow down the processor's clock speed. Power varies in direct proportion to frequency so you get control over power, at the cost of performance. More advanced chips can do some of this automatically, similar to Transmeta's LongRun, AMD's PowerNow, or Intel's SpeedStep technologies. To get really fancy, though, the chip needs access to a variable power DAC (digital-to-analog converter) to dial in its own power supply. Nobody offers this yet because the embedded systems that are most concerned with power are generally also the ones most concerned with size, weight, and cost, thus making variable power DACs somewhat unattractive.

Time was, embedded processors were looked down upon as the chips that couldn't make it in "real" computers. Now that those "real computers" are less than 2% of the overall market, embedded seems like a pretty good place to be. And with so-called embedded processors now sporting eight-way superscalar and VLIW designs, with speculative execution, they're not so low- end, either.

There's a lot more innovation going on in embedded processors than there is in the PC space. PC's are constrained by compatibility issues and an endless chase for more straight-line performance (and software applications that make use of it). Embedded systems, however, are all over the map – literally. There's no such thing as a typical embedded processor and no single right way to do something. It's fun to watch if you're a processor nerd.

"There's a lot more innovation going on in embedded processors than there is in the PC space. PC's are constrained by compatibility issues and an endless chase for more straight-line performance."

Embedded processors also tie into everyday life in the real world (RW) more than other children of technology. Next year's hot gift will probably be driven by a new embedded processor or two. Or four. It's not about "where do you want to go today" it's about "what do you want for your birthday?" A key factor in embedded success is getting to the one-spouse decision: the price point at which you can buy yourself a cool new gadget without asking permission first. Economists say that point is around $299; below that, sales take off.

Amdahl's Law says that computers are limited by bandwidth, not performance. Moore's Law says we get more transistors to play with all the time. Eveready's Law, unfortunately, grows battery power much more slowly than our appetite to consume it. Finally, Turley's Law (my own humble contribution to journalists' amusement) says that the amount of processing power you carry on your body doubles every two years. Pat yourself down and see if you're not already carrying more computing horsepower than NASA left on the surface of the moon. And it only gets better from here.

Copyright (c) 2001 Ziff Davis Media Inc. All Rights Reserved.

NYTimes(Tech): “Honey, I Programmed the Blanket”

NYTimes(Tech): “Honey, I Programmed the Blanket”

The Omnipresent Chip Has Invaded Everything From Dishwashers to Dogs

The average middle-class American household has about 40 microprocessors in it. If you own a PC, with all the paraphernalia that goes with it, that number increases to about 50.

There's a microprocessor, or chip, in a bathroom scale with a digital readout, and there's one in an iron that turns itself off automatically. An average electronic toothbrush has 3,000 lines of computer code. On the more sophisticated end of the spectrum, there's a smoke detector that places a call to the fire department, a dishwasher with sensors that gauge the soil level of the water and adjusts its cycle accordingly and an identification tag placed under a pet's skin.

Known as embedded microprocessors (or, in a simpler form, microcontrollers), these invisible chips are far more numerous than those that drive desktop or portable computers. Tom Starnes, an analyst at Dataquest, a market research company, said that the number of embedded processors sold in 1998 was 4.8 billion and that only about 120 million of them, about 2.5 percent, had been intended for personal computers.

PC's, video games and smart phones get all the attention as symbols of the electronic age. But the chips that really make this age electronic are almost completely hidden. It may seem like the era of the personal computer. It is just as much, if not more, the era of the hidden chip.

And chips will be found in even more places in the future. Starnes estimated that in five years, the average number of chips in the home could grow to 280 and the number sold to 9.4 billion. The tough question in predicting the future is figuring out what won't have computing power in it.

An embedded chip is any processor that is not inside a computer. Its job is to make its presence barely known. It can lie at the heart of something as trivial as a musical greeting card or as vital to life as a pacemaker, which uses a processor to analyze signals from the heart and determine if the heart needs some help.

"Almost anything with a power switch now has a microprocessor in it," said Peter N. Glaskowsky, a senior analyst at Micro Design Resources, which publishes Microprocessor Report, a newsletter.

In accord with Moore's Law, which states that the density of chips doubles every 18 months, the semiconductor industry has steadily found ways to shrink the size of chips and increase their performance. "The same thing that would have filled a room in the 50's is now on a chip that costs $1.95 and sits in a microwave," said Jim Turley, vice president of marketing for ARC, a microprocessor design company based in London. "It's really a pretty spectacular thing to watch."

The result has been a profusion of chips in everyday objects: toothbrushes, cars, kitchen appliances, office buildings, toys and sports gear. "If the engineers can dream it, they'll do it," said Guy Thomsen, an applications and support manager at Hitachi Semiconductor in San Jose, Calif.