Six things you may not know about JavaScript

Six things you may not know about JavaScript 관련

So, you’re a JavaScript developer? Nice to hear — what do you think this code returns? And yeah, it’s a trick question:

function returnSomething() {

return {

name: 'JavaScript Expert'

contactMethod: 'Shine batsign at sky'

}

}

In almost any other language — C#, Java, the list goes on — we’d get back the object with JavaScript Expert. And you’d be forgiven for thinking that in JavaScript, we’d get back the same result.

However, humor me, and pop this into your development console, and then execute the function. Almost unbelievably, it returnsundefined.

When things don’t go to plan

Working as a software developer means that you are responsible for how your app works, whether it works well or poorly. A main constraint in that is the tools that you decide to use. If you understand what you’re using, you’ll hopefully make good choices in how you design your software.

JavaScript is unique because it’s the language of choice of so many new software developers. Want to write a mobile app? Just use React Native and JavaScript. Desktop app? React Native and JavaScript. A cloud function to run somewhere? Node.js, and, you guessed it, JavaScript.

However, due to how long JavaScript has been around, it has its fair share of footguns and gotchas. Some of these range from mildly amusing to none-of-my-code-works-and-I-don’t-know-why severity.

And, even if we lived in a time when Internet Explorer 6 was in its heyday, it would simply be too late to go and try to fix some of these design decisions, as we would break too much of the web. If that were the case then, imagine if we tried today! 🌍💥

So, how does JavaScript not work in a way that we might expect? Let’s take a look.

Automatic Semicolon Injection (ASI)

The example listed at the outset is accepted by JavaScript interpreters but doesn’t yield the expected result. The reason is because of Automatic Semicolon Injection.

Some languages, like C#, are dogmatic about ending each line with a semicolon. JavaScript also uses semicolons to indicate the end of a line, but the semicolon is actually optional. By optional, it means that JavaScript will apply a set of complex rules to work out whether a semicolon should have gone there or not.

In the example at the outset, because the opening bracket doesn’t occur on the same line as the return, ASI pops one in there for us. So, as far as JavaScript is concerned, our code actually looks like this:

function returnSomething() {

return ; // <-- semicolon inserted by ASI, remainder of function not evaluated.

{

name: 'JavaScript Expert'

contactMethod: 'Shine batsign at sky'

}

}

The way to avoid this is to have the opening bracket on the same line as a return. And, while semicolons are technically optional in JavaScript, it’s going to hurt you in the long run to work with that concept.

If you have an interview, and you have to write JS, and you write it without semicolons based on the rationale “but they’re optional,” there’s going to be a lot of paper shuffling and chuckling. Just don’t do it.

Arrays with non-sequential keys

Let’s imagine we have a simple array:

var array = [];

We know we can pop, push, append, and do whatever we like with arrays. But we also know that JavaScript, like other languages, lets us access array elements by index.

However, what’s unusual about JavaScript is that you can also set elements by array index when the array isn’t even up to that index just yet:

array[0] = "first element";

array[1] = "second element";

array[100] = "wait what?";

I’ve got a good question for you though — what’s the length of an array when you’ve only set three elements? Possibly non-intuitively, it’s 101. On one hand, it’s reasonable that array items 2 through 99 are undefined, but on the other, we only set three objects, not 100. Why does it matter?

Maybe your eyes roll out of your head and you say, “OK Lewis, you’re manually assigning items into an array and watching the wheels come off; that makes you weird, not JavaScript.”

I would understand that position. But imagine for a moment you’re doing something in a nested for loop, and you choose the wrong iterator or make a bunk calculation.

At some point, the thought process of “why am I getting expected result, expected result, undefined, expected result” is going to turn to madness, and soon enough to tears! Little did you know your array magically grew to accommodate what you were trying to do.

The only problem was, you were trying to do the wrong thing.

Compared to another language, like C# (for no particular reason), arrays are of fixed length. When you create an array, you have to define a length. Even for other dynamic collection objects, like List<T>, you can’t assign into an undefined index. So, if your nested loop attempts to write to a previously unassigned index, your program will throw.

Exceptions aren’t nice, but it’s probably the right thing to do. I mean, did you otherwise mean to create a Swiss cheese array? Does anyone mean to do that? Hopefully not.

It’s only Swiss cheese arrays if the developers are from Switzerland. Otherwise, it’s just sparkling bad programming.

Adding properties to primatives are ignored

We know that in JavaScript we can assign new functions to prototypes. So, we can give strings or arrays ✨special powers✨. Of course, doing so is terrible practice because it means that our string prototype will behave differently to others, which already causes untold heartache for many a developer.

So, we can do this for example:

String.prototype.alwaysReturnsFalse = () => false;

And then we can create a string object:

var itsAString = "hooray";

itsAString.alwaysReturnsFalse();

And it would return false.

It’s cute we can always just randomly jam our functions into the factory-defined implementation of how a string can act.

Sure, all those good people broke their backs and spent tens of thousands of hours defining JavaScript in the TC39 specification, but don’t let that dissuade you from banging in your random functions as you see fit.

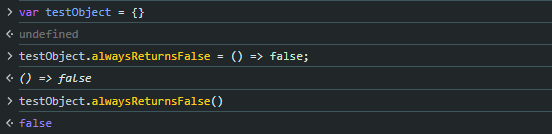

If we’re not happy with that particular brand of pain, we can also randomly assign new functions to complex objects as we want to, ensuring that our code will be a very particular form of nonsense, understood only by yourself and God:

Composing our objects like this is naturally a terrible idea, but as we are committed to this treachery, JavaScript obliges us in our request. Our testObject takes on the new function we’ve thrown into it.

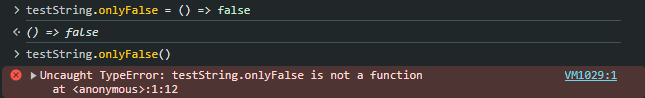

However, the good will runs out with object primatives, in a surprising way:

The interpreter acknowledges our attempt to assign a function into the string primative. It even echoes the function back to us. But then, when we attempt to call it, we get a TypeError: testString.onlyFalse is not a function. If it’s not possible to do this, typically you would expect this to throw on assignation, not on function call.

Why does it matter?

For better or for worse, JavaScript is a highly flexible and dynamic language. This flexibility allows us to compose functionality that’s not possible in other languages. If something hasn’t worked, then we should expect an exception. JavaScript taking this awkward command and being like “uh, OK” and then forgetting about it changes this fundamental expectation.

Type coercion

In other strongly typed languages, we have to define the type of the data that we’re storing before we’re able to store it. JavaScript doesn’t have this same kind of limitation, and it will happily nudge objects away from their defined type to try to get them to play nice together.

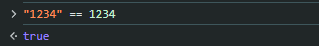

On one hand, it gets us away from casting variables back and forth to their respective types. So it’s convenient:

Thanks for saving me from a Number(x) call!

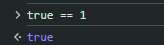

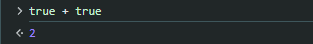

It’s even the same for booleans:

I mean, I guess…

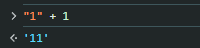

This approach is completely sane and valid until we want to involve ourselves in the taboo ritual known as “addition.” When we try to add "1" and 1 together, what happens? What way does the type coercion go?

The insanity hilarity multiplies when we bring bool to the party:

Oh — is it because a bool is somehow a number under the hood?

Nope. It’s a boolean. JavaScript is shaving off the pesky edges of the square to fit it into that round hole because reasons.

Why does it matter?

When you’re doing something as basic as adding numbers together, having results vary can create some weird bugs. It’s a good reminder to stick to the triple equals (===) when making comparisons, as zapping between types may not give you the intended result.

Function hoisting

With languages that we use today, an important aspect is something called “function hoisting.” Essentially, it means that you can write your functions in your file wherever you like, and you’ll be able to call them before the functions are declared:

foo();

function foo(){

console.log("test");

}

It’s handy because we don’t have to manually reorder our code to make it work.

But, there’s more than one way to describe a function. In this example, we used a function declaration to do so. We can also use a function expression:

foo(); //TypeError: foo is not a function!

var foo = function() {

console.log("test");

}

Why does it matter?

There’s not a huge difference between declaring functions in either case, but if you choose the wrong one, you won’t be able to call your function unless you’re calling it after you’ve declared it.

Null is an object

Within other languages, object properties can be assigned, or they can be null. null indicates that the property is not assigned. It’s simple to equate in our heads — there’s either an object there, or it’s null. We can also assign properties back to null if we so wish.

JavaScript complicates this landscape by having null and also undefined. But it’s all the same, right? You either have a ball in your hand, or you don’t.

Unsurprisingly, it’s not all the same. In JavaScript, null indicates the intentional lack of a value, whereas undefined indicates the implied lack of a value. So, whether it’s intentional, explicit, or written in the sky, the fact is that a no value = no value, right?

Again, unfortunately, that’s not how the equation works out.

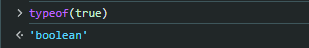

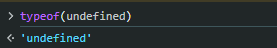

Well, what’s the type of undefined?

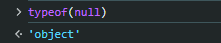

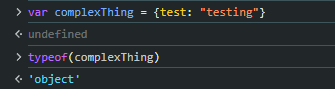

Okay, and what’s the type of null?

🤯 it’s an object*.* So in JavaScript, the type of a complex object and null are the same — they’re both object:

Why does it matter?

JavaScript doesn’t have a robust type-checking system built in, and there’s only a handful of primative types to choose from. So, using typeof to understand what’s in our variable can become tricky. If our variable holds a valid object, then we’d get object. But if it’s null, we’d still get object. It’s counter-intuitive to think that a null reference is an object.

Conclusion

There’s no questioning of JavaScript’s immense popularity today as a language. As time continues and other ecosystems such as npm continue to host huge numbers of packages, JavaScript will only continue increasing in popularity.

But what’s done is done. No matter how weird it is that null is an object, or that JavaScript will pop semicolons in where it sees fit, these systems will probably never be deprecated, changed, or removed. Anecdotally, I would say that if Automatic Semicolon Injection was turned off overnight, it’d probably cause a bigger global outage than the CrowdStrike update would.

Certainly, changing one of these would wreak havoc on the web. It’s actually safer, and probably more practical, to make the developers aware of these particular language quirks than to actually go back and resolve the original problems.

So, go and make good choices, and don’t forget to use semicolons!