Loading our data and splitting up words: filter()

Loading our data and splitting up words: filter() 관련

The next step in our project is to get our app working a little bit, which means writing a method that loads the input text and splits it up into words. Sticking with TDD for now, this means we first need to write a test that fails before updating our code to fix it.

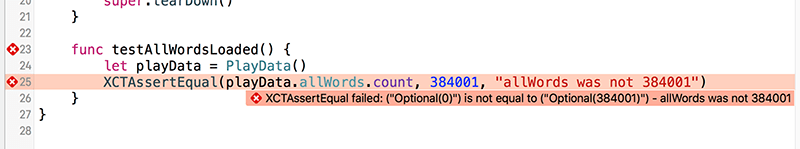

Right now we're checking allWords contains 0 items, which needs to change: there are in fact 384,001 words in the input text (based on the character splitting criteria we'll get to shortly), so please update your testAllWordsLoaded() method to this:

XCTAssertEqual(playData.allWords.count, 384001, "allWords was not 384001")

This number, 384,001, is of course entirely arbitrary because it depends on the input data. But that's not the point: we need to tell XCTest what "correct" looks like, because it has no way of knowing what constitutes a pass or a fail unless we give it specific criteria.

If you click the green checkmark next to the test now, it will be run again and will fail this time because we haven't written the loading code - XCTest expects allWords to contain 384,001 strings, but it contains 0. This is good, honest!

Let's put testing to one side for now and fill in some of our program - we'll be back with the testing soon enough, don't worry.

Add this to PlayData.swift:

init() {

if let path = Bundle.main.path(forResource: "plays", ofType: "txt") {

if let plays = try? String(contentsOfFile: path) {

allWords = plays.components(separatedBy: CharacterSet.alphanumerics.inverted)

}

}

}

The only new line there is the one that sets allWords, which uses two new things at once. Previously we used components(separatedBy:) to convert a string into an array, but this time the method is different because we pass in a character set rather than string. This new method splits a string by any number of characters rather than a single string, which is important because we want to split on periods, question marks, exclamation marks, quote marks and more.

There are a number of ways of specifying character sets, including a helpful CharacterSet(charactersIn:) initializer that we could have used to specify the full list of characters we want to break on. But the simplest approach is to split on anything that isn't a letter or number, which can be achieved by inverting the alphanumeric character set as seen in the code.

That's all it takes to load enough data for us to move on with, but we can't tell that it works unless we also update the user interface to show our data. So, open ViewController.swift and add this property:

var playData = PlayData()

That gives the ViewController class its own PlayData object to work with. That one line also creates the object immediately, which in turn will call the init() method we just wrote to load the word data - not bad for a single line of code!

All that's left in this step is to add the basic table view code to show some cells. Please add these two methods to ViewController:

override func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, numberOfRowsInSection section: Int) -> Int {

return playData.allWords.count

}

override func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, cellForRowAt indexPath: IndexPath) -> UITableViewCell {

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: "Cell", for: indexPath)

let word = playData.allWords[indexPath.row]

cell.textLabel!.text = word

return cell

}

There is nothing new there, so I hope it posed no challenge for you.

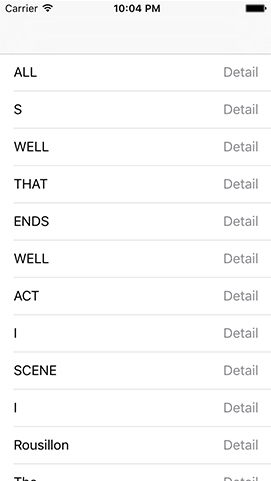

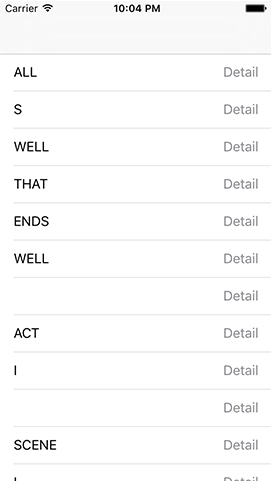

Press Cmd+R to run the app and you'll see a long table full of words - it works! It's a long way from perfect, though: it's breaking on apostrophes (so ALL and S are on different lines), there are blank lines, there are duplicate words (the I after ACT and SCENE is repeated), and the detail text label just says "Detail" again and again.

We're going to fix all those except the first one, which is a text issue rather than a coding issue. In fact, we need to fix the second one straight away because my calculation of 384,001 words excludes empty strings - we need to modify our init() method so that empty strings are removed if we want our test to pass.

As promised, I'm going to use this project to teach you a little bit of functional programming, in particular the filter() method. This creates a new array from an existing one, selecting from it only items that match a function you provide. Stick with me for a moment, because this is important: a function that accepts a function as a parameter, like filter(), is called a higher-order function, and allows you to write extremely concise, expressive code that is efficient to run.

Let's take a look at filter() now. Please add this to init(), just after the call to components(separatedBy:):

allWords = allWords.filter { $0 != "" }

That one line is all it takes to remove empty lines from the allWords array. However, this syntax can look like line noise if you're new to Swift, so I want to deconstruct what it does by first rewriting that code in a way you're more familiar with. I don't want you to put any of this into your code - this is just to help you understand what's going on.

Here is that one line written out more verbosely:

allWords = allWords.filter({ (testString: String) -> Bool in

if testString != "" {

return true

} else {

return false

}

})

In that form, you can see that filter() is a method that takes a single parameter, which is a closure. That closure must accept a string, named testString, and return a Bool. The code then checks whether testString is empty or not, and returns either true or false.

Swift lives up to its name not only in that Swift code executes quickly, but it's also quick to write. So, there are a few shortcuts it offers to help reduce that long code down in size. For example, all that (testString: String) -> Bool definition isn't really needed: Swift can see that filter() wants a closure that accepts a string and returns true or false, so we don't need to repeat ourselves. So, let's take it out:

allWords = allWords.filter({ testString in

if testString != "" {

return true

} else {

return false

}

})

Next, we can collapse that if/else block into one line of code: return testString != "".

When Swift runs testString != "" it will either find that statement to be true (yes, testString is not empty) or false (no, testString is empty), and pass that straight to return. So, this will return true if testString has any text, which is exactly what we want.

With that change, here's the code now:

allWords = allWords.filter({ testString in

return testString != ""

})

Moving on, we can take advantage of Swift's trailing closure syntax, because filter()'s only parameter is a closure. If you remember, that means the parentheses aren't needed. So, the code can become this:

allWords = allWords.filter { testString in

return testString != ""

}

Next, if your closure has only one expression - which ours does - and the closure must return a value, Swift lets you omit the return keyword entirely. This is because it knows the closure must return a value, and it can see you're only providing one line of code, so that must be the one that returns something. So, you can write this:

allWords = allWords.filter { testString in

testString != ""

}

And now for the bit that usually confuses people: shorthand parameter names. When you use a closure like this, Swift automatically creates anonymous parameter names that start with a dollar sign then have a number: $0, $1, $2, $3 and so on. This unique naming really helps them stand out, so if you see them in code you immediately know they are shorthand parameter names - you literally cannot use names like this yourself, so they only have one meaning.

Swift gives you one of these shorthand parameters for every parameter that your closure accepts. In this case, our filter closure accepts exactly one parameter, which is testString. If we want to use Swift's shorthand parameter names instead, we don't need testString any more because testString and $0, so that whole testString in part can go away:

allWords = allWords.filter {

$0 != ""

}

Now all that's left is to put that on a single line, and we're done:

allWords = allWords.filter { $0 != "" }

Now, even though I've explained the thinning process that goes from long code to tiny code, you might still look at that one line and find it confusing. That's OK: you should write code however you want to write code. But in this instance, I hope you'll agree that having one simple, clutter-free line of code is easier to read, understand, and maintain than five or six lines.

Now that empty lines are being stripped out, you should be able to return back to testAllWordsLoaded() and have it pass.