Why Non-Blocking?

Why Non-Blocking? 관련

Non-blocking systems have become more commonplace and accessible due to the rich choice of tools and programming approaches. But in my current experience, programmers used to a more traditional blocking approach tend to quickly become confused about non-blocking or reactive systems, at times even confusing the terms "non-blocking" with "asynchronicity".

In this article we will review the current status of blocking systems by building and examining a simple Spring Boot application. We will talk about how they behave. Then we will introduce Kotlin Coroutines, and how they can help us to model our non-blocking services.

The Servlet Container

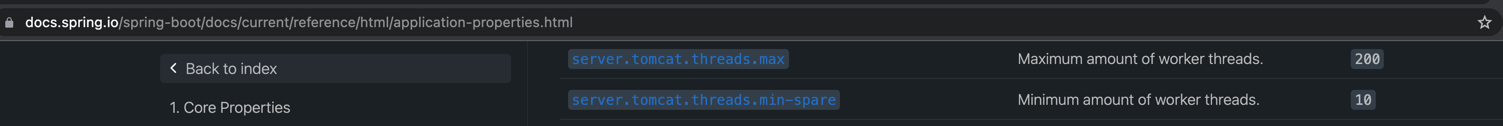

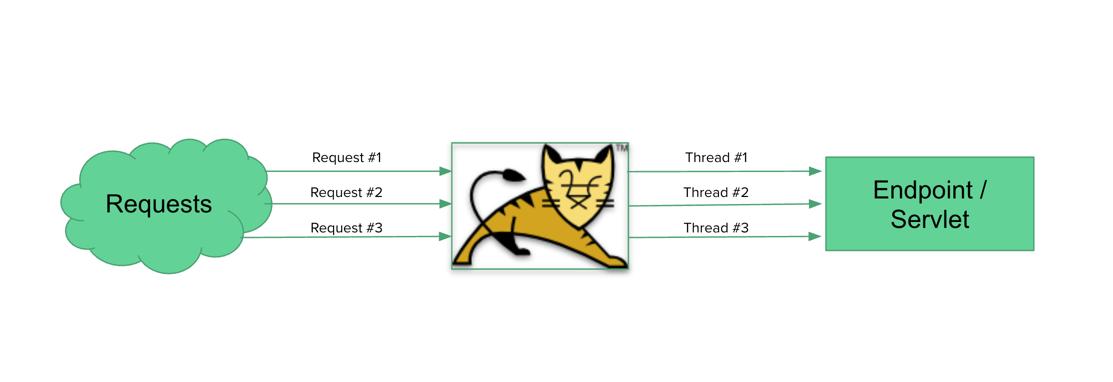

In traditional Servlet container web services, every incoming request is served by its own thread. In our Spring Boot environment, this is what we get out of the box when importing the spring-web-starter (also known as Spring Web MVC). A Tomcat container is included, and some sensible defaults configured when using this dependency:

Spring Web Dependency

By default, a spring-web application configures 10 "warm" threads and a ceiling of 200 max-threads for incoming requests:

In other words: If you have 3 incoming requests, there are 3 threads in use. If you have 100 incoming requests, 100 threads in use, and so on.

Let us create a very simple Spring MVC service: We will implement a simple Rest Controller with two endpoints: One will return a simple greeting, and the other a collection of greetings after processing our request. We will also cap this Spring service to have a maximum of 10 threads total. This will allow us to experiment exhausting them without running extensive test suites.

Creating the Service

We will create a service that returns customized greetings to users based on their request.

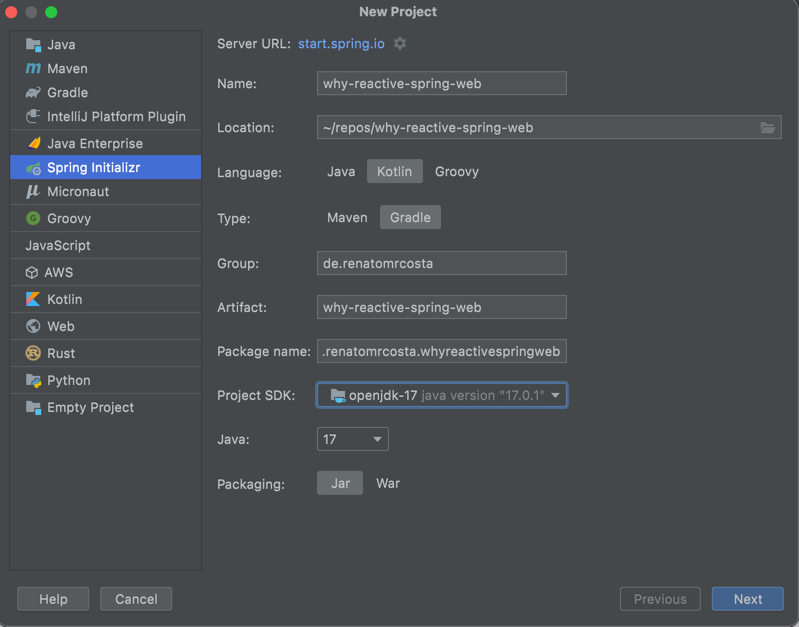

Either go to https://start.spring.io to create your project, or use the much more practical [New Project Window] -> [Spring Initializr] in IDEA:

We will add solely the spring-web dependency for the time being. After it is generated, add the following to the application.properties (or application.yml) file in /src/resources:

server.tomcat.threads.max=10

server.tomcat.threads.min-spare=10

Creating the endpoints

We will create very simple endpoints, and quite literally mock complex behavior for brevity's sake. Our controller shall have two get methods:

/greeting-> will return all possible greetings in our system/greeting/{id}-> will return a greeting if the id valid, otherwise a 404. The important thing about our service is that searching for greetings is contrived to be an 'expensive' operation. Think of it as accessing a remote service, a third-party API or a database: there's obviously some network and processing overhead to get the necessary result.

A prototype of how it could look like is as follows:

Data Model representation:

data class Greeting(val id: Int, val text: String)

Service providing those greetings:

@Service

class GreetingService {

private val hardCodedGreetings = listOf(

Greeting(id = 1, text = "Hello there!"),

Greeting(id = 2, text = "Howdy Partner!"),

Greeting(id = 3, text = "Well, that's a fine how do you do!"),

)

fun getAll(): List<Greeting> {

trace("Starting work to get all greetings")

Thread.sleep(1_000) // Simulates a really slow amount of work, 1 sec of total pause

return hardCodedGreetings.also {

trace("Got all greetings!")

}

}

fun getById(id: Int): Greeting? {

trace("Starting work to get a specific greeting")

Thread.sleep(1_000) // Simulates a really slow amount of work, 1 sec of total pause

return hardCodedGreetings.firstOrNull { it.id == id }.also {

trace("Got specific greeting")

}

}

}

Our controller:

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/greeting")

class GreetingController(

private val greetingService: GreetingService,

) {

@GetMapping

fun listAll(): List<Greeting> = greetingService.getAll()

@GetMapping("/{id}")

fun getById(@PathVariable id: Int): ResponseEntity<Greeting> =

greetingService.getById(id = id)?.let { greeting ->

ResponseEntity.ok(greeting)

} ?: ResponseEntity.notFound().build()

}

Note that we also implemented a little helper function to print the current thread name + a log message:

private fun trace(msg: Any) {

println("[${Thread.currentThread().name}] $msg")

}

When running our application, one can navigate to http://localhost:8080/greeting to play around with our setup. Our service is up and running! Whatever could go wrong?

Stressing it

Given what we know about the Servlet behavior, and that our application is configured to only serve requests using a maximum of 10 threads, what would happen if we got something like 50 requests simultaneously?

Let us run a small script. For instance, this dummy JavaScript code that you can run in the Chrome console:

for (var i = 0; i< 50; i++) { fetch("http://localhost:8080/greeting") }

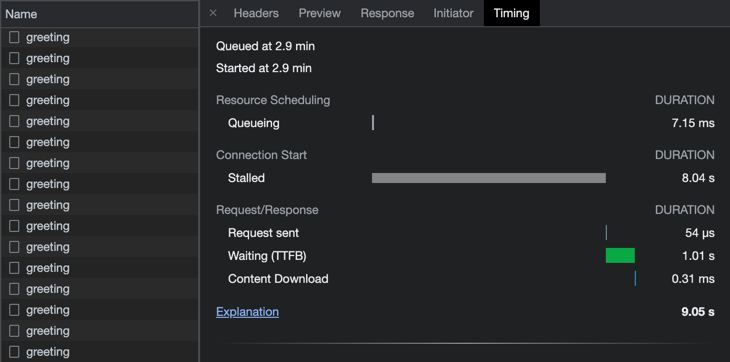

Look at our server console: As soon as all threads are blocked, the remaining requests must wait until the work done in order to occupy another free slot. In your browser's network tab, you may also notice that the requests take much longer in total, given their waiting time:

So what, then?

This example was certainly very contrived! A request that takes a full second, and a dearth of threads are not normally common indeed. But I hope this may have triggered your consideration for problems in larger scale. Even if you dimension your Tomcat to serve 1000 threads, you will still be at the mercy of such issues when waiting for external calls.

The actual problem is that creating and managing threads is expensive, at least in our JVM World. Even if we nowadays live in the land of plenty, where machines are provisioned and we can just throw more memory and CPU at the problem until it vanishes, we certainly need a better approach to manage our throughput without depending on spawning thousands of threads when we try to scale our services.

Non-blocking for the win

In our code, we have contrived a blocking call (in this case, a Thread.sleep call) to block the worker thread. In essence, this is the same as using a RestTemplate call, or a java.net.HttpClient call. Those Components and APIs are blocking, in the sense that they occupy the calling thread until they have a meaningful result.

Let's then move our delay behavior out of our Service classes, and utilize an external delay API:

Configures the client

@Configuration

class HttpClientConfiguration {

@Bean

fun javaClient(): java.net.http.HttpClient = java.net.http.HttpClient.newHttpClient()

}

Implements the delay call

@Service

class DelayService(

private val javaClient: java.net.http.HttpClient,

) {

fun delay() {

val request = HttpRequest.newBuilder()

.uri(URI.create("$ENDPOINT_URL/$DELAY_SECONDS"))

.GET()

.build()

javaClient.send(request, HttpResponse.BodyHandlers.ofString())

}

companion object {

private const val ENDPOINT_URL = "https://httpbin.org/delay"

private const val DELAY_SECONDS = 1

}

}

Changes the call in our Service class

@Service

class GreetingService(

private val delayService: DelayService,

) {

private val hardCodedGreetings = listOf(

Greeting(id = 1, text = "Hello there!"),

Greeting(id = 2, text = "Howdy Partner!"),

Greeting(id = 3, text = "Well, that's a fine how do you do!"),

)

fun getAll(): List<Greeting> {

trace("Starting work to get all greetings")

delayService.delay()

return hardCodedGreetings.also {

trace("Got all greetings!")

}

}

fun getById(id: Int): Greeting? {

trace("Starting work to get a specific greeting")

delayService.delay()

return hardCodedGreetings.firstOrNull { it.id == id }.also {

trace("Got specific greeting")

}

}

}

If you re-run our caller Script example from above, the behavior will still be the same: the HTTP Request still blocks.

One could then utilize then some sort of strategy (as using the Async APIs with a Completable Future) to avoid blocking the calling thread: By subscribing some sort of callback to the remote call we can defer the resolution:

@Service

class DelayService(

private val javaClient: java.net.http.HttpClient,

) {

fun delay() {

val request = HttpRequest.newBuilder()

.uri(URI.create("$ENDPOINT_URL/$DELAY_SECONDS"))

.GET()

.build()

val future = javaClient.sendAsync(request, HttpResponse.BodyHandlers.ofString())

future.thenAccept {

trace("Waiting finished with status ${it.statusCode()}")

}

}

companion object {

private const val ENDPOINT_URL = "https://httpbin.org/delay"

private const val DELAY_SECONDS = 1

}

}

While we improve by not blocking unnecessarily in the remote request, we lose in introducing some complexity on how to deal with the particular completable future introduced by whichever library our Client is utilizing. How could we improve our situation even further?

Coroutines, or how I stopped worrying about non-blocking code and started loving the code

Coroutines (or more specifically Kotlin Coroutines) are basically devices that allow the non-blocking execution of code, and this code can be suspended and later resumed. In a really reductive nutshell, coroutines are akin to lightweight-threads. If you haven't been introduced yet, I highly recommend watching Roman Elizarov's talk in Kotlin Conf 2017, and also having a look at the amazing documentation provided by Jetbrains.

One important statement you can take away from this intro: Nowadays, waiting gracefully is probably more important than raw computation! And providing an idiomatic and intuitive way to wait gracefully is one of the superpowers coroutines grant us!

So, how can we tell if coroutines are truly akin to lightweight threads? Let's run a small code sample to figure it out.

Take the following piece of code: With it, we shall build a list of threads and run then concurrently, contriving a 1 second long piece of work, joining them at the end, and see how long our parallel process took in total. An analogous piece of code for coroutines follows in the bottom:

import util.withExecutionTime

import kotlin.concurrent.thread

fun main() {

// This block will execute, and the execution time will be printed out in milliseconds

measureTimeMillis {

// A list with a number of items will spawn. Each item will initialize using the block of code below

List(100) {

thread {

Thread.sleep(1000)

trace("Executed Thread #$it")

}

}.onEach {

// Wait until the thread spawned is done working before proceeding

it.join()

}

}.also { trace("Executed in ${it}ms")}

}

import kotlinx.coroutines.delay

import kotlinx.coroutines.launch

import kotlinx.coroutines.runBlocking

import util.trace

import util.withExecutionTime

fun main() {

// This block will execute, and the execution time will be printed out in milliseconds

measureTimeMillis {

// This block will bridge the blocking and non-blocking execution, and create a coroutine scope

runBlocking {

// A list with a number of items will spawn. Each item will initialize using the block of code below

List(100) {

launch {

delay(1000)

trace("Executed Job #$it")

}

}

}

}.also { trace("Executed in ${it}ms") }

}

If one runs these pieces of code with 100 units of work, we almost universally reach the 1 second + some overhead amount of execution time. Now imagine we needed to run 10 million units of work: The coroutine enabled code easily handles it, while most laptops will certainly buckle under the memory requirements from the Thread example!

Now, if we have an inexpensive model for using threads in coroutines, can we take advantage of it in our servers?

Migrating towards coroutines

Since Spring Boot 2.4, even servlet based services have support for coroutines! To get started, let's add the appropriate dependencies to our build.gradle file:

val coroutinesVersion = "1.5.2"

implementation (dependencyNotation: "org.jetbrains.kotlinx:kotlinx-coroutines-core:$coroutinesVersion")

// adds the necessary depenencies to Tomcat servlets to behave non-blocking / suspending

implementation (dependency Notation: "org.jetbrains.kotlinx:kotlinx-coroutines-reactor:$coroutinesVersion")

// Convenience Extension functions to deal with JDK8 futures

implementation (dependencyNotation: "org.jetbrains.kotlinx:kotlinx-coroutines-jdk8:$coroutinesVersion")

And now, we can take advantage of two things:

- Adding the

suspendkeyword to our controller / function calls: This is, essentially, a contract we establish in our application, indicating that the operations therein will not block the caller thread. - Use a simple helper function to avoid having to define callbacks / operators in our non-blocking or asynchronous functions.

Our code will look, in summary, like this:

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/greeting")

class GreetingController(

private val greetingService: GreetingService,

) {

@GetMapping

suspend fun listAll(): List<Greeting> = greetingService.getAll()

@GetMapping("/{id}")

suspend fun getById(@PathVariable id: Int): ResponseEntity<Greeting> =

greetingService.getById(id = id)?.let { greeting ->

ResponseEntity.ok(greeting)

} ?: ResponseEntity.notFound().build()

}

@Service

class GreetingService(

private val delayService: DelayService,

) {

private val hardCodedGreetings = listOf(

Greeting(id = 1, text = "Hello there!"),

Greeting(id = 2, text = "Howdy Partner!"),

Greeting(id = 3, text = "Well, that's a fine how do you do!"),

)

suspend fun getAll(): List<Greeting> {

trace("Starting work to get all greetings")

delayService.delay()

return hardCodedGreetings.also {

trace("Got all greetings!")

}

}

suspend fun getById(id: Int): Greeting? {

trace("Starting work to get a specific greeting")

delayService.delay()

return hardCodedGreetings.firstOrNull { it.id == id }.also {

trace("Got specific greeting")

}

}

}

data class Greeting(val id: Int, val text: String)

private fun trace(msg: Any) {

println("\[${Thread.currentThread().name}\] $msg")

}

@Service

class DelayService(

private val javaClient: java.net.http.HttpClient,

) {

suspend fun delay() {

val request = HttpRequest.newBuilder()

.uri(URI.create("$ENDPOINT_URL/$DELAY_SECONDS"))

.GET()

.build()

val response = javaClient

.sendAsync(request, HttpResponse.BodyHandlers.ofString())

.await() // Awaits without blocking!

// This line executes after the response is received

trace("Waiting finished with status ${response.statusCode()}")

}

companion object {

private const val ENDPOINT_URL = "https://httpbin.org/delay"

private const val DELAY_SECONDS = 1

}

}

@Configuration

class HttpClientConfiguration {

@Bean

fun javaClient(): java.net.http.HttpClient = java.net.http.HttpClient.newHttpClient()

}

(As an aside, I would also recommend looking into alternatives to Java's HTTP client that plays nicer in a coroutine environment, such as Spring's WebClient, Ktor Client, kittinunf/fuel, etc.)

As one can see, now our delayService just uses an await() function to wait for the response of our remote request, while yielding the processing resources of its thread to other operations. It reads as simple imperative code, but waits gracefully for the response without blocking the Thread.

If you run our test script once again, look at how the result differs:

Even though the amount of request vastly exceeds the number of available threads, we are able to gracefully handle the burst of requests with the available resources, no sweat!

From non-blocking to reactive

One may be asking themselves then, how can we go from here to truly reactive services? We are basically halfway there!

Using coroutines in Kotlin helps us to avoid dealing with complex Reactor / RxJava types and APIs. For instance: When we define a suspend request mapping returning a value (like suspend fun get(): Greeting), we are actually defining we return an equivalent value of suspend fun get(): Mono<Greeting>).

The coroutines specification allows developers to work with Kotlin idiomatically no matter what, even to work with more complex types such as Flow (the equivalent of Reactor's Flux).

Spring provides us with the spring-webflux starter that utilizes a Netty server framework instead of Tomcat. In this case, we don't define a thread-pool to handle our incoming requests, but it instead defines a CPU-bound thread-pool based on the machine's number of CPU Cores to serve all incoming requests. Normal laptops and even servers have appreciably less CPU cores than 200, so not blocking threads is an absolute must!

In Conclusion

There's much and more we could talk about the power and flexibility of using coroutines in our systems are able to provide us: We started from a typical Spring Web Servlet, with all our naive calls blocking our service. We transitioned into a non-blocking implementation by adding the coroutine support that Spring Boot provides out of the box, and appreciated how changing just a little in our setup we can extract much more from our current resources. We saw that asynchronous calls in our webclient are non-blocking, but also verified that there may be calls that do not block but behave synchronously (our await() call). And we hopefully demystified the basic usages of coroutines in conjunction with Spring Boot

Info

The code for this project can be found here

This article was originally published on Renato Costa's blog.