Rust enum and match representation in assembly

Rust enum and match representation in assembly 관련

Rust enum-match code generation

Matching an enum and associated fields

Enums in Rust are discriminated unions that can save one of the multiple variants. The enum discriminator identifies the current interpretation of the discriminated union.

The following code shows a simple enum in Rust that represents a generalized Number that can be an Integer, a Float or Complex. Here Number is a container that can store a 64-bit integer (i64), a 64-bit floating-point number (f64) or a complex number (stored in a struct with two f64 fields).

The code following the enum declaration declares a function double that takes a Number parameter and returns a Number that doubles the fields of whatever type of Number is found in the enum. The match statement in Rust is used to pattern match the contents and return the appropriate variant.

pub enum Number {

Integer(i64),

Float(f64),

Complex { real: f64, imaginary: f64 },

}

pub fn double(num: Number) -> Number {

match num {

Number::Integer(n) => Number::Integer(n + n),

Number::Float(n) => Number::Float(n + n),

Number::Complex { real, imaginary } => Number::Complex {

real: real + real,

imaginary: imaginary + imaginary,

},

}

}

Memory layout of a Rust enum

Before we proceed any further, let's look at the enum organization in memory. The size of the enum depends upon the largest variant. This example a Number::Complex requires two 64-bit floats. The total memory needed for the variant is 16 bytes. The size of the enum is 24 bytes. The extra 8 bytes are used to store a 64-bit discriminator that is used to identify the variant currently saved in the enum.

| Byte offset | Integer | Float | Complex |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Discriminator (0) | Discriminator (1) | Discriminator (2) |

| 8 | i64 | f64 | f64 |

| 16 | f64 |

Note

Note: A 64-bit discriminator might seem wasteful here. Due to padding rules, a smaller discriminator would not have saved any memory. Rust does switch to a smaller discriminator when reducing the size permits addition of smaller fields.

Overview of the generated code

Before we dig deep into the assembly, let's get an overview of the generated code via the following flowchart. The code branches based on the enum discriminator and handles the processing of each enum tag separately. The results and the discriminator values are written at the provided return address.

Deep dive into the generated code

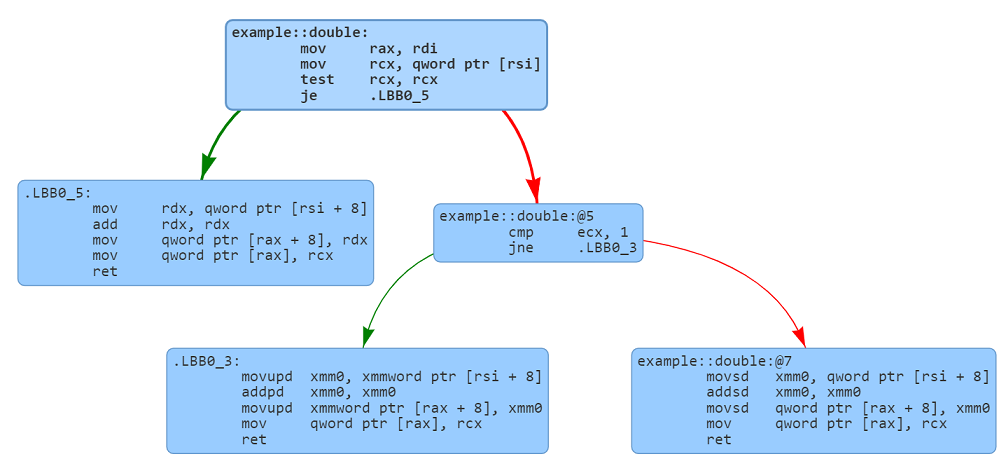

Now that we understand the basic flow of the generated code, let's analyze the generated assembly code. The following graph shows the branching structure of the generated assembly. The top box and middle-right boxes check the discriminator and then invoke the appropriate variant handling code (the three leaf boxes).

Let's now look at each line of the generated assembly. We have annotated the assembly code to aid in the understanding of the code. The generated code looks at the discriminator and then accesses the fields corresponding to selected variants. The code then doubles the individual fields associated with the variant. The enum with doubled values is returned from the function. The function also copies the discriminator field to the enum that is being returned.

; The caller passes the following parameters:

; 🔡 rsi: Address of the enum

; 🔡 rdi: Address of the enum to be returned.

example::double:

mov rax, rdi ; rax now contains the address to the return value

mov rcx, qword ptr [rsi] ; Extract the union discriminator

test rcx, rcx ; Check if the discriminator is 0 (Number::Integer)

je .LBB0_5 ; Jump if the discriminator is 0.

cmp ecx, 1 ; Check if the discriminator is 1 (Number::Float).

jne .LBB0_3 ; Jump if discriminator is 2 (Number::Complex)

; ⭐ Number::Float match processing (discriminator is 1)

movsd xmm0, qword ptr [rsi + 8] ; Move the floating point number in xmm0

addsd xmm0, xmm0 ; Double the number

movsd qword ptr [rax + 8], xmm0 ; Save in value in the return value

mov qword ptr [rax], rcx ; Copy the discriminator into the return value

ret

.LBB0_5:

; ⭐ Number::Integer match processing (discriminator is 0)

mov rdx, qword ptr [rsi + 8] ; Move the integer

add rdx, rdx ; Double the number

mov qword ptr [rax + 8], rdx ; Write the number to the return value

mov qword ptr [rax], rcx ; Write the discriminator to the return value

ret

.LBB0_3:

; ⭐ Number::Complex match processing (discriminator is 2)

; The following code performs vector operations on the real and imaginary parts.

; The vector operations 64-bit real and imaginary parts are processed in parallel

; in the xmm0 register.

movupd xmm0, xmmword ptr [rsi + 8] ; Read the real and imaginary parts into xmm0

addpd xmm0, xmm0 ; Double the real and imaginary parts

movupd xmmword ptr [rax + 8], xmm0 ; Update the real and imaginary parts

mov qword ptr [rax], rcx ; Set the discriminator in the return value

ret

Key takeaways

- The Rust compiler adds an extra 8 bytes to the enum to store the discriminator. This is used to identify the variant currently stored in the enum.

- The size of the enum depends upon the largest variant. In this example, the largest variant is

Number::Complexthat requires 16 bytes. The discriminator is 64-bits wide and hence requires 8 bytes. - The size of the discriminator depends upon the range of values that can be stored in the enum. However, in most scenarios, the alignment requirements dictate the size of the discriminator.

- The generated assembly code branches based on the discriminator and then processes the fields of the variant.

Experiment in the Compiler Explorer

Experiment in the Compiler Explorer with the code in this post. Change the Number enum to use 32-bit types as shown below. The enum discriminator field is 32-bit.

pub enum Number {

Integer(i32),

Float(f32),

Complex { real: f32, imaginary: f32 },

}