Printing in a Nutshell

Printing in a Nutshell 관련

Let’s jump in by looking at a few real-life examples of printing in Python. By the end of this section, you’ll know every possible way of calling print(). Or, in programmer lingo, you’d say you’ll be familiar with the function signature.

Calling print()

The simplest example of using Python print() requires just a few keystrokes:

print()

You don’t pass any arguments, but you still need to put empty parentheses at the end, which tell Python to actually execute the function rather than just refer to it by name.

This will produce an invisible newline character, which in turn will cause a blank line to appear on your screen. You can call print() multiple times like this to add vertical space. It’s just as if you were hitting Enter on your keyboard in a word processor.

Newline Character

A newline character is a special control character used to indicate the end of a line (EOL). It usually doesn’t have a visible representation on the screen, but some text editors can display such non-printable characters with little graphics.

The word “character” is somewhat of a misnomer in this case, because a newline is often more than one character long. For example, the Windows operating system, as well as the HTTP protocol, represent newlines with a pair of characters. Sometimes you need to take those differences into account to design truly portable programs.

To find out what constitutes a newline in your operating system, use Python’s built-in os module.

This will immediately tell you that Windows and DOS represent the newline as a sequence of \r followed by \n:

import os

os.linesep

#

# '\r\n'

On Unix, Linux, and recent versions of macOS, it’s a single \n character:

import os

os.linesep

#

# '\n'

The classic Mac OS X, however, sticks to its own “think different” philosophy by choosing yet another representation:

import os

os.linesep

#

# '\r'

Notice how these characters appear in string literals. They use special syntax with a preceding backslash (``) to denote the start of an escape character sequence. Such sequences allow for representing control characters, which would be otherwise invisible on screen.

Most programming languages come with a predefined set of escape sequences for special characters such as these:

\: backslash\b: backspace\t: tab\r: carriage return (CR)\n: newline, also known as line feed (LF)

The last two are reminiscent of mechanical typewriters, which required two separate commands to insert a newline. The first command would move the carriage back to the beginning of the current line, while the second one would advance the roll to the next line.

By comparing the corresponding ASCII character codes, you’ll see that putting a backslash in front of a character changes its meaning completely. However, not all characters allow for this-only the special ones.

To compare ASCII character codes, you may want to use the built-in ord() function:

ord('r')

#

# 114

ord('\r')

#

# 13

Keep in mind that, in order to form a correct escape sequence, there must be no space between the backslash character and a letter!

As you just saw, calling print() without arguments results in a blank line, which is a line comprised solely of the newline character. Don’t confuse this with an empty line, which doesn’t contain any characters at all, not even the newline!

You can use Python’s string literals to visualize these two:

'\n' # Blank line

'' # Empty line

The first one is one character long, whereas the second one has no content.

Note

To remove the newline character from a string in Python, use its .rstrip() method, like this:

'A line of text.\n'.rstrip()

#

# 'A line of text.'

This strips any trailing whitespace from the right edge of the string of characters.

In a more common scenario, you’d want to communicate some message to the end user. There are a few ways to achieve this.

First, you may pass a string literal directly to print():

print('Please wait while the program is loading...')

This will print the message verbatim onto the screen.

String Literals

String literals in Python can be enclosed either in single quotes (') or double quotes ("). According to the official PEP 8 style guide, you should just pick one and keep using it consistently. There’s no difference, unless you need to nest one in another.

For example, you can’t use double quotes for the literal and also include double quotes inside of it, because that’s ambiguous for the Python interpreter:

"My favorite book is "Python Tricks"" # Wrong!

What you want to do is enclose the text, which contains double quotes, within single quotes:

'My favorite book is "Python Tricks"'

The same trick would work the other way around:

"My favorite book is 'Python Tricks'"

Alternatively, you could use escape character sequences mentioned earlier, to make Python treat those internal double quotes literally as part of the string literal:

"My favorite book is \"Python Tricks\""

Escaping is fine and dandy, but it can sometimes get in the way. Specifically, when you need your string to contain relatively many backslash characters in literal form.

One classic example is a file path on Windows:

'C:\Users\jdoe' # Wrong!

'C:\\Users\\jdoe'

Notice how each backslash character needs to be escaped with yet another backslash.

This is even more prominent with regular expressions, which quickly get convoluted due to the heavy use of special characters:

'^\\w:\\\\(?:(?:(?:[^\\\]+)?|(?:[^\\\]+)\\\[^\\\]+)*)$'

Fortunately, you can turn off character escaping entirely with the help of raw-string literals. Simply prepend an r or R before the opening quote, and now you end up with this:

r'C:\Users\jdoe'

r'^\w:\\(?:(?:(?:[^\]+)?|(?:[^\]+)\[^\]+)*)$'

That’s much better, isn’t it?

There are a few more prefixes that give special meaning to string literals in Python, but you won’t get into them here.

Lastly, you can define multi-line string literals by enclosing them between ''' or """, which are often used as docstrings.

Here’s an example:

"""

This is an example

of a multi-line string

in Python.

"""

To prevent an initial newline, simply put the text right after the opening """:

"""This is an example

of a multi-line string

in Python.

"""

You can also use a backslash to get rid of the newline:

"""\

This is an example

of a multi-line string

in Python.

"""

To remove indentation from a multi-line string, you might take advantage of the built-in textwrap module:

import textwrap

paragraph = '''

This is an example

of a multi-line string

in Python.

'''

print(paragraph)

#

# This is an example

# of a multi-line string

# in Python.

print(textwrap.dedent(paragraph).strip())

#

# This is an example

# of a multi-line string

# in Python.

This will take care of unindenting paragraphs for you. There are also a few other useful functions in textwrap for text alignment you’d find in a word processor.

:::

Secondly, you could extract that message into its own variable with a meaningful name to enhance readability and promote code reuse:

message = 'Please wait while the program is loading...'

print(message)

Lastly, you could pass an expression, like string concatenation, to be evaluated before printing the result:

import os

print('Hello, ' + os.getlogin() + '! How are you?')

#

# Hello, jdoe! How are you?

In fact, there are a dozen ways to format messages in Python. I highly encourage you to take a look at f-strings, introduced in Python 3.6, because they offer the most concise syntax of them all:

import os

print(f'Hello, {os.getlogin()}! How are you?')

Moreover, f-strings will prevent you from making a common mistake, which is forgetting to type cast concatenated operands. Python is a strongly typed language, which means it won’t allow you to do this:

'My age is ' + 42

#

# Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "<input>", line 1, in <module>

# 'My age is ' + 42

# TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

That’s wrong because adding numbers to strings doesn’t make sense. You need to explicitly convert the number to string first, in order to join them together:

'My age is ' + str(42)

#

# 'My age is 42'

Unless you handle such errors yourself, the Python interpreter will let you know about a problem by showing a traceback.

Note

str() is a global built-in function that converts an object into its string representation.

You can call it directly on any object, for example, a number:

str(3.14)

#

# '3.14'

Built-in data types have a predefined string representation out of the box, but later in this article, you’ll find out how to provide one for your custom classes.

As with any function, it doesn’t matter whether you pass a literal, a variable, or an expression. Unlike many other functions, however, print() will accept anything regardless of its type.

So far, you only looked at the string, but how about other data types? Let’s try literals of different built-in types and see what comes out:

print(42) # <class 'int'>

#

# 42

print(3.14) # <class 'float'>

#

# 3.14

print(1 + 2j) # <class 'complex'>

#

# (1+2j)

print(True) # <class 'bool'>

#

# True

print([1, 2, 3]) # <class 'list'>

#

# [1, 2, 3]

print((1, 2, 3)) # <class 'tuple'>

#

# (1, 2, 3)

print({'red', 'green', 'blue'}) # <class 'set'>

#

# {'red', 'green', 'blue'}

print({'name': 'Alice', 'age': 42}) # <class 'dict'>

#

# {'name': 'Alice', 'age': 42}

print('hello') # <class 'str'>

#

# hello

Watch out for the None constant, though. Despite being used to indicate an absence of a value, it will show up as 'None' rather than an empty string:

print(None)

#

# None

How does print() know how to work with all these different types? Well, the short answer is that it doesn’t. It implicitly calls str() behind the scenes to type cast any object into a string. Afterward, it treats strings in a uniform way.

Later in this tutorial, you’ll learn how to use this mechanism for printing custom data types such as your classes.

Okay, you’re now able to call print() with a single argument or without any arguments. You know how to print fixed or formatted messages onto the screen. The next subsection will expand on message formatting a little bit.

Syntax in Python 2

To achieve the same result in the previous language generation, you’d normally want to drop the parentheses enclosing the text:

# Python 2

print

print 'Please wait...'

print 'Hello, %s! How are you?' % os.getlogin()

print 'Hello, %s. Your age is %d.' % (name, age)

That’s because print wasn’t a function back then, as you’ll see in the next section. Note, however, that in some cases parentheses in Python are redundant. It wouldn’t harm to include them as they’d just get ignored. Does that mean you should be using the print statement as if it were a function? Absolutely not!

For example, parentheses enclosing a single expression or a literal are optional. Both instructions produce the same result in Python 2:

# Python 2

print 'Please wait...'

#

# Please wait...

print('Please wait...')

#

# Please wait...

Round brackets are actually part of the expression rather than the print statement. If your expression happens to contain only one item, then it’s as if you didn’t include the brackets at all.

On the other hand, putting parentheses around multiple items forms a tuple:

# Python 2

print 'My name is', 'John'

#

# My name is John

print('My name is', 'John')

#

# ('My name is', 'John')

This is a known source of confusion. In fact, you’d also get a tuple by appending a trailing comma to the only item surrounded by parentheses:

# Python 2

print('Please wait...')

#

# Please wait...

print('Please wait...',) # Notice the comma

#

# ('Please wait...',)

The bottom line is that you shouldn’t call print with brackets in Python 2. Although, to be completely accurate, you can work around this with the help of a __future__ import, which you’ll read more about in the relevant section.

Separating Multiple Arguments

You saw print() called without any arguments to produce a blank line and then called with a single argument to display either a fixed or a formatted message.

However, it turns out that this function can accept any number of positional arguments, including zero, one, or more arguments. That’s very handy in a common case of message formatting, where you’d want to join a few elements together.

Positional Arguments

Arguments can be passed to a function in one of several ways. One way is by explicitly naming the arguments when you’re calling the function, like this:

def div(a, b):

return a / b

div(a=3, b=4)

#

# 0.75

Since arguments can be uniquely identified by name, their order doesn’t matter. Swapping them out will still give the same result:

div(b=4, a=3)

#

# 0.75

Conversely, arguments passed without names are identified by their position. That’s why positional arguments need to follow strictly the order imposed by the function signature:

div(3, 4)

#

# 0.75

div(4, 3)

#

# 1.3333333333333333

print() allows an arbitrary number of positional arguments thanks to the *args parameter.

:::

Let’s have a look at this example:

import os

print('My name is', os.getlogin(), 'and I am', 42)

#

# My name is jdoe and I am 42

print() concatenated all four arguments passed to it, and it inserted a single space between them so that you didn’t end up with a squashed message like 'My name isjdoeand I am42'.

Notice that it also took care of proper type casting by implicitly calling str() on each argument before joining them together. If you recall from the previous subsection, a naïve concatenation may easily result in an error due to incompatible types:

print('My age is: ' + 42)

#

# Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "<input>", line 1, in <module>

# print('My age is: ' + 42)

# TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

Apart from accepting a variable number of positional arguments, print() defines four named or keyword arguments, which are optional since they all have default values. You can view their brief documentation by calling help(print) from the interactive interpreter.

Let’s focus on sep just for now. It stands for separator and is assigned a single space (' ') by default. It determines the value to join elements with.

It has to be either a string or None, but the latter has the same effect as the default space:

print('hello', 'world', sep=None)

#

# hello world

print('hello', 'world', sep=' ')

#

# hello world

print('hello', 'world')

#

# hello world

If you wanted to suppress the separator completely, you’d have to pass an empty string ('') instead:

print('hello', 'world', sep='')

#

# helloworld

You may want print() to join its arguments as separate lines. In that case, simply pass the escaped newline character described earlier:

print('hello', 'world', sep='\n')

#

# hello

# world

A more useful example of the sep parameter would be printing something like file paths:

print('home', 'user', 'documents', sep='/')

#

# home/user/documents

Remember that the separator comes between the elements, not around them, so you need to account for that in one way or another:

print('/home', 'user', 'documents', sep='/')

#

# /home/user/documents

print('', 'home', 'user', 'documents', sep='/')

#

# /home/user/documents

Specifically, you can insert a slash character (/) into the first positional argument, or use an empty string as the first argument to enforce the leading slash.

Note

Be careful about joining elements of a list or tuple.

Doing it manually will result in a well-known TypeError if at least one of the elements isn’t a string:

print(' '.join(['jdoe is', 42, 'years old']))

#

# Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "<input>", line 1, in <module>

# print(','.join(['jdoe is', 42, 'years old']))

# TypeError: sequence item 1: expected str instance, int found

It’s safer to just unpack the sequence with the star operator (*) and let print() handle type casting:

print(*['jdoe is', 42, 'years old'])

#

# jdoe is 42 years old

Unpacking is effectively the same as calling print() with individual elements of the list.

One more interesting example could be exporting data to a comma-separated values (CSV) format:

print(1, 'Python Tricks', 'Dan Bader', sep=',')

#

# 1,Python Tricks,Dan Bader

This wouldn’t handle edge cases such as escaping commas correctly, but for simple use cases, it should do. The line above would show up in your terminal window. In order to save it to a file, you’d have to redirect the output. Later in this section, you’ll see how to use print() to write text to files straight from Python.

Finally, the sep parameter isn’t constrained to a single character only. You can join elements with strings of any length:

print('node', 'child', 'child', sep=' -> ')

#

# node -> child -> child

In the upcoming subsections, you’ll explore the remaining keyword arguments of the print() function.

Syntax in Python 2

To print multiple elements in Python 2, you must drop the parentheses around them, just like before:

import os

print 'My name is', os.getlogin(), 'and I am', 42

#

# My name is jdoe and I am 42

If you kept them, on the other hand, you’d be passing a single tuple element to the print statement:

import os

print('My name is', os.getlogin(), 'and I am', 42)

#

# ('My name is', 'jdoe', 'and I am', 42)

Moreover, there’s no way of altering the default separator of joined elements in Python 2, so one workaround is to use string interpolation like so:

import os

print 'My name is %s and I am %d' % (os.getlogin(), 42)

#

# My name is jdoe and I am 42

That was the default way of formatting strings until the .format() method got backported from Python 3.

Preventing Line Breaks

Sometimes you don’t want to end your message with a trailing newline so that subsequent calls to print() will continue on the same line. Classic examples include updating the progress of a long-running operation or prompting the user for input. In the latter case, you want the user to type in the answer on the same line:

Are you sure you want to do this? [y/n] y

Many programming languages expose functions similar to print() through their standard libraries, but they let you decide whether to add a newline or not. For example, in Java and C#, you have two distinct functions, while other languages require you to explicitly append \n at the end of a string literal.

Here are a few examples of syntax in such languages:

| Language | Example |

|---|---|

| Perl | print "hello world\n" |

| C | printf("hello world\n"); |

| C++ | std::cout << "hello world" << std::endl; |

In contrast, Python’s print() function always adds \n without asking, because that’s what you want in most cases. To disable it, you can take advantage of yet another keyword argument, end, which dictates what to end the line with.

In terms of semantics, the end parameter is almost identical to the sep one that you saw earlier:

- It must be a string or

None. - It can be arbitrarily long.

- It has a default value of

'\n'. - If equal to

None, it’ll have the same effect as the default value. - If equal to an empty string (

''), it’ll suppress the newline.

Now you understand what’s happening under the hood when you’re calling print() without arguments. Since you don’t provide any positional arguments to the function, there’s nothing to be joined, and so the default separator isn’t used at all. However, the default value of end still applies, and a blank line shows up.

Note

You may be wondering why the end parameter has a fixed default value rather than whatever makes sense on your operating system.

Well, you don’t have to worry about newline representation across different operating systems when printing, because print() will handle the conversion automatically. Just remember to always use the \n escape sequence in string literals.

This is currently the most portable way of printing a newline character in Python:

print('line1\nline2\nline3')

#

# line1

# line2

# line3

If you were to try to forcefully print a Windows-specific newline character on a Linux machine, for example, you’d end up with broken output:

print('line1\r\nline2\r\nline3')

#

# line3

On the flip side, when you open a file for reading with open(), you don’t need to care about newline representation either. The function will translate any system-specific newline it encounters into a universal '\n'. At the same time, you have control over how the newlines should be treated both on input and output if you really need that.

To disable the newline, you must specify an empty string through the end keyword argument:

print('Checking file integrity...', end='')

# (...)

print('ok')

Even though these are two separate print() calls, which can execute a long time apart, you’ll eventually see only one line. First, it’ll look like this:

Checking file integrity...

However, after the second call to print(), the same line will appear on the screen as:

Checking file integrity...ok

As with sep, you can use end to join individual pieces into a big blob of text with a custom separator. Instead of joining multiple arguments, however, it’ll append text from each function call to the same line:

print('The first sentence', end='. ')

print('The second sentence', end='. ')

print('The last sentence.')

These three instructions will output a single line of text:

The first sentence. The second sentence. The last sentence.

You can mix the two keyword arguments:

print('Mercury', 'Venus', 'Earth', sep=', ', end=', ')

print('Mars', 'Jupiter', 'Saturn', sep=', ', end=', ')

print('Uranus', 'Neptune', 'Pluto', sep=', ')

Not only do you get a single line of text, but all items are separated with a comma:

Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Pluto

There’s nothing to stop you from using the newline character with some extra padding around it:

print('Printing in a Nutshell', end='\n * ')

print('Calling Print', end='\n * ')

print('Separating Multiple Arguments', end='\n * ')

print('Preventing Line Breaks')

It would print out the following piece of text:

Printing in a Nutshell

* Calling Print

* Separating Multiple Arguments

* Preventing Line Breaks

As you can see, the end keyword argument will accept arbitrary strings.

Note

Looping over lines in a text file preserves their own newline characters, which combined with the print() function’s default behavior will result in a redundant newline character:

with open('file.txt') as file_object:

for line in file_object:

print(line)

#

# Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod

#

# tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam,

#

# quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo

There are two newlines after each line of text. You want to strip one of the them, as shown earlier in this article, before printing the line:

print(line.rstrip())

Alternatively, you can keep the newline in the content but suppress the one appended by print() automatically. You’d use the end keyword argument to do that:

with open('file.txt') as file_object:

for line in file_object:

print(line, end='')

#

# Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod

# tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam,

# quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo

By ending a line with an empty string, you effectively disable one of the newlines.

You’re getting more acquainted with printing in Python, but there’s still a lot of useful information ahead. In the upcoming subsection, you’ll learn how to intercept and redirect the print() function’s output.

Syntax in Python 2

Preventing a line break in Python 2 requires that you append a trailing comma to the expression:

print 'hello world',

However, that’s not ideal because it also adds an unwanted space, which would translate to end=' ' instead of end='' in Python 3. You can test this with the following code snippet:

print 'BEFORE'

print 'hello',

print 'AFTER'

Notice there’s a space between the words hello and AFTER:

BEFORE

hello AFTER

In order to get the expected result, you’d need to use one of the tricks explained later, which is either importing the print() function from __future__ or falling back to the sys module:

import sys

print 'BEFORE'

sys.stdout.write('hello')

print 'AFTER'

This will print the correct output without extra space:

BEFORE

helloAFTER

While using the sys module gives you control over what gets printed to the standard output, the code becomes a little bit more cluttered.

Printing to a File

Believe it or not, print() doesn’t know how to turn messages into text on your screen, and frankly it doesn’t need to. That’s a job for lower-level layers of code, which understand bytes and know how to push them around.

print() is an abstraction over these layers, providing a convenient interface that merely delegates the actual printing to a stream or file-like object. A stream can be any file on your disk, a network socket, or perhaps an in-memory buffer.

In addition to this, there are three standard streams provided by the operating system:

stdin: standard inputstdout: standard outputstderr: standard error

Standard Streams

Standard output is what you see in the terminal when you run various command-line programs including your own Python scripts:

cat hello.py

#

# print('This will appear on stdout')

python hello.py

#

# This will appear on stdout

Unless otherwise instructed, print() will default to writing to standard output. However, you can tell your operating system to temporarily swap out stdout for a file stream, so that any output ends up in that file rather than the screen:

python hello.py > file.txt

cat file.txt

#

# This will appear on stdout

That’s called stream redirection.

The standard error is similar to stdout in that it also shows up on the screen. Nonetheless, it’s a separate stream, whose purpose is to log error messages for diagnostics. By redirecting one or both of them, you can keep things clean.

Note

To redirect stderr, you need to know about file descriptors, also known as file handles.

They’re arbitrary, albeit constant, numbers associated with standard streams. Below, you’ll find a summary of the file descriptors for a family of POSIX-compliant operating systems:

| Stream | File Descriptor |

|---|---|

stdin | 0 |

stdout | 1 |

stderr | 2 |

Knowing those descriptors allows you to redirect one or more streams at a time:

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

./program > out.txt | Redirect stdout |

./program 2> err.txt | Redirect stderr |

./program > out.txt 2> err.txt | Redirect stdout and stderr to separate files |

./program &> out_err.txt | Redirect stdout and stderr to the same file |

Note that > is the same as 1>.

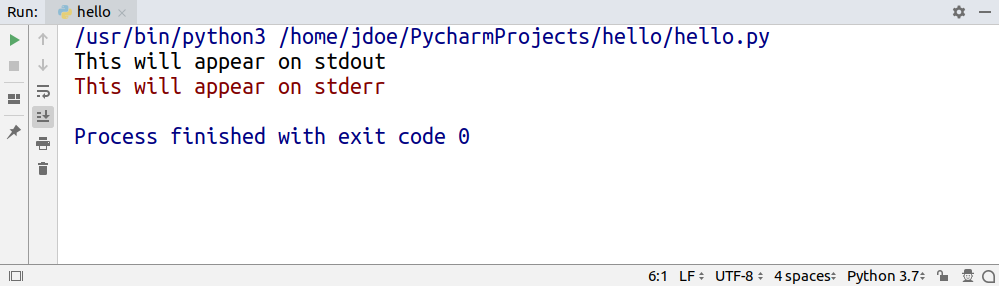

Some programs use different coloring to distinguish between messages printed to stdout and stderr:

While both stdout and stderr are write-only, stdin is read-only. You can think of standard input as your keyboard, but just like with the other two, you can swap out stdin for a file to read data from.

In Python, you can access all standard streams through the built-in sys module:

import sys

sys.stdin

#

# <_io.TextIOWrapper name='<stdin>' mode='r' encoding='UTF-8'>

sys.stdin.fileno()

#

# 0

sys.stdout

#

# <_io.TextIOWrapper name='<stdout>' mode='w' encoding='UTF-8'>

sys.stdout.fileno()

#

# 1

sys.stderr

#

# <_io.TextIOWrapper name='<stderr>' mode='w' encoding='UTF-8'>

sys.stderr.fileno()

#

# 2

As you can see, these predefined values resemble file-like objects with mode and encoding attributes as well as .read() and .write() methods among many others.

By default, print() is bound to sys.stdout through its file argument, but you can change that. Use that keyword argument to indicate a file that was open in write or append mode, so that messages go straight to it:

with open('file.txt', mode='w') as file_object:

print('hello world', file=file_object)

This will make your code immune to stream redirection at the operating system level, which might or might not be desired.

For more information on working with files in Python, you can check out Reading and Writing Files in Python (Guide).

Note

Don’t try using print() for writing binary data as it’s only well suited for text.

Just call the binary file’s .write() directly:

with open('file.dat', 'wb') as file_object:

file_object.write(bytes(4))

file_object.write(b'\xff')

If you wanted to write raw bytes on the standard output, then this will fail too because sys.stdout is a character stream:

import sys

sys.stdout.write(bytes(4))

#

# Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

# TypeError: write() argument must be str, not bytes

You must dig deeper to get a handle of the underlying byte stream instead:

import sys

num_bytes_written = sys.stdout.buffer.write(b'\x41\x0a')

#

# A

This prints an uppercase letter A and a newline character, which correspond to decimal values of 65 and 10 in ASCII. However, they’re encoded using hexadecimal notation in the bytes literal.

Note that print() has no control over character encoding. It’s the stream’s responsibility to encode received Unicode strings into bytes correctly. In most cases, you won’t set the encoding yourself, because the default UTF-8 is what you want. If you really need to, perhaps for legacy systems, you can use the encoding argument of open():

with open('file.txt', mode='w', encoding='iso-8859-1') as file_object:

print('über naïve café', file=file_object)

Instead of a real file existing somewhere in your file system, you can provide a fake one, which would reside in your computer’s memory. You’ll use this technique later for mocking print() in unit tests:

import io

fake_file = io.StringIO()

print('hello world', file=fake_file)

fake_file.getvalue()

#

# 'hello world\n'

If you got to this point, then you’re left with only one keyword argument in print(), which you’ll see in the next subsection. It’s probably the least used of them all. Nevertheless, there are times when it’s absolutely necessary.

Syntax in Python 2

There’s a special syntax in Python 2 for replacing the default sys.stdout with a custom file in the print statement:

with open('file.txt', mode='w') as file_object:

print >> file_object, 'hello world'

Because strings and bytes are represented with the same str type in Python 2, the print statement can handle binary data just fine:

with open('file.dat', mode='wb') as file_object:

print >> file_object, '\x41\x0a'

Although, there’s a problem with character encoding. The open() function in Python 2 lacks the encoding parameter, which would often result in the dreadful UnicodeEncodeError:

with open('file.txt', mode='w') as file_object:

unicode_text = u'\xfcber na\xefve caf\xe9'

print >> file_object, unicode_text

#

# Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "<stdin>", line 3, in <module>

# UnicodeEncodeError: 'ascii' codec can't encode character u'\xfc'...

Notice how non-Latin characters must be escaped in both Unicode and string literals to avoid a syntax error. Take a look at this example:

unicode_literal = u'\xfcber na\xefve caf\xe9'

string_literal = '\xc3\xbcber na\xc3\xafve caf\xc3\xa9'

Alternatively, you could specify source code encoding according to PEP 263 at the top of the file, but that wasn’t the best practice due to portability issues:

#!/usr/bin/env python2

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

unescaped_unicode_literal = u'über naïve café'

unescaped_string_literal = 'über naïve café'

Your best bet is to encode the Unicode string just before printing it. You can do this manually:

with open('file.txt', mode='w') as file_object:

unicode_text = u'\xfcber na\xefve caf\xe9'

encoded_text = unicode_text.encode('utf-8')

print >> file_object, encoded_text

However, a more convenient option is to use the built-in codecs module:

import codecs

with codecs.open('file.txt', 'w', encoding='utf-8') as file_object:

unicode_text = u'\xfcber na\xefve caf\xe9'

print >> file_object, unicode_text

It’ll take care of making appropriate conversions when you need to read or write files.

Buffering print() Calls

In the previous subsection, you learned that print() delegates printing to a file-like object such as sys.stdout. Some streams, however, buffer certain I/O operations to enhance performance, which can get in the way. Let’s take a look at an example.

Imagine you were writing a countdown timer, which should append the remaining time to the same line every second:

3...2...1...Go!

Your first attempt may look something like this:

import time

num_seconds = 3

for countdown in reversed(range(num_seconds + 1)):

if countdown > 0:

print(countdown, end='...')

time.sleep(1)

else:

print('Go!')

As long as the countdown variable is greater than zero, the code keeps appending text without a trailing newline and then goes to sleep for one second. Finally, when the countdown is finished, it prints Go! and terminates the line.

Unexpectedly, instead of counting down every second, the program idles wastefully for three seconds, and then suddenly prints the entire line at once:

That’s because the operating system buffers subsequent writes to the standard output in this case. You need to know that there are three kinds of streams with respect to buffering:

- Unbuffered

- Line-buffered

- Block-buffered

Unbuffered is self-explanatory, that is, no buffering is taking place, and all writes have immediate effect. A line-buffered stream waits before firing any I/O calls until a line break appears somewhere in the buffer, whereas a block-buffered one simply allows the buffer to fill up to a certain size regardless of its content. Standard output is both line-buffered and block-buffered, depending on which event comes first.

Buffering helps to reduce the number of expensive I/O calls. Think about sending messages over a high-latency network, for example. When you connect to a remote server to execute commands over the SSH protocol, each of your keystrokes may actually produce an individual data packet, which is orders of magnitude bigger than its payload. What an overhead! It would make sense to wait until at least a few characters are typed and then send them together. That’s where buffering steps in.

On the other hand, buffering can sometimes have undesired effects as you just saw with the countdown example. To fix it, you can simply tell print() to forcefully flush the stream without waiting for a newline character in the buffer using its flush flag:

print(countdown, end='...', flush=True)

That’s all. Your countdown should work as expected now, but don’t take my word for it. Go ahead and test it to see the difference.

Congratulations! At this point, you’ve seen examples of calling print() that cover all of its parameters. You know their purpose and when to use them. Understanding the signature is only the beginning, however. In the upcoming sections, you’ll see why.

Syntax in Python 2

There isn’t an easy way to flush the stream in Python 2, because the print statement doesn’t allow for it by itself. You need to get a handle of its lower-level layer, which is the standard output, and call it directly:

import time

import sys

num_seconds = 3

for countdown in reversed(range(num_seconds + 1)):

if countdown > 0:

sys.stdout.write('%s...' % countdown)

sys.stdout.flush()

time.sleep(1)

else:

print 'Go!'

Alternatively, you could disable buffering of the standard streams either by providing the -u flag to the Python interpreter or by setting up the PYTHONUNBUFFERED environment variable:

python2 -u countdown.py

PYTHONUNBUFFERED=1 python2 countdown.py

Note that print() was backported to Python 2 and made available through the __future__ module. Unfortunately, it doesn’t come with the flush parameter:

from __future__ import print_function

help(print)

#

# Help on built-in function print in module __builtin__:

#

# print(...)

# print(value, ..., sep=' ', end='\n', file=sys.stdout)

What you’re seeing here is a docstring of the print() function. You can display docstrings of various objects in Python using the built-in help() function.

Printing Custom Data Types

Up until now, you only dealt with built-in data types such as strings and numbers, but you’ll often want to print your own abstract data types. Let’s have a look at different ways of defining them.

For simple objects without any logic, whose purpose is to carry data, you’ll typically take advantage of namedtuple, which is available in the standard library. Named tuples have a neat textual representation out of the box:

from collections import namedtuple

Person = namedtuple('Person', 'name age')

jdoe = Person('John Doe', 42)

print(jdoe)

#

# Person(name='John Doe', age=42)

That’s great as long as holding data is enough, but in order to add behaviors to the Person type, you’ll eventually need to define a class. Take a look at this example:

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name, self.age = name, age

If you now create an instance of the Person class and try to print it, you’ll get this bizarre output, which is quite different from the equivalent namedtuple:

jdoe = Person('John Doe', 42)

print(jdoe)

#

# <__main__.Person object at 0x7fcac3fed1d0>

It’s the default representation of objects, which comprises their address in memory, the corresponding class name and a module in which they were defined. You’ll fix that in a bit, but just for the record, as a quick workaround you could combine namedtuple and a custom class through inheritance:

from collections import namedtuple

class Person(namedtuple('Person', 'name age')):

pass

Your Person class has just become a specialized kind of namedtuple with two attributes, which you can customize.

Note

In Python 3, the pass statement can be replaced with the ellipsis (...) literal to indicate a placeholder:

def delta(a, b, c):

...

This prevents the interpreter from raising IndentationError due to missing indented block of code.

That’s better than a plain namedtuple, because not only do you get printing right for free, but you can also add custom methods and properties to the class. However, it solves one problem while introducing another. Remember that tuples, including named tuples, are immutable in Python, so they can’t change their values once created.

It’s true that designing immutable data types is desirable, but in many cases, you’ll want them to allow for change, so you’re back with regular classes again.

Note

Following other languages and frameworks, Python 3.7 introduced data classes, which you can think of as mutable tuples. This way, you get the best of both worlds:

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Person:

name: str

age: int

def celebrate_birthday(self):

self.age += 1

jdoe = Person('John Doe', 42)

jdoe.celebrate_birthday()

print(jdoe)

#

# Person(name='John Doe', age=43)

The syntax for variable annotations, which is required to specify class fields with their corresponding types, was defined in Python 3.6.

From earlier subsections, you already know that print() implicitly calls the built-in str() function to convert its positional arguments into strings. Indeed, calling str() manually against an instance of the regular Person class yields the same result as printing it:

jdoe = Person('John Doe', 42)

str(jdoe)

#

# '<__main__.Person object at 0x7fcac3fed1d0>'

str(), in turn, looks for one of two magic methods within the class body, which you typically implement. If it doesn’t find one, then it falls back to the ugly default representation. Those magic methods are, in order of search:

def __str__(self)def __repr__(self)

The first one is recommended to return a short, human-readable text, which includes information from the most relevant attributes. After all, you don’t want to expose sensitive data, such as user passwords, when printing objects.

However, the other one should provide complete information about an object, to allow for restoring its state from a string. Ideally, it should return valid Python code, so that you can pass it directly to eval():

repr(jdoe)

#

# "Person(name='John Doe', age=42)"

type(eval(repr(jdoe)))

#

# <class '__main__.Person'>

Notice the use of another built-in function, repr(), which always tries to call .__repr__() in an object, but falls back to the default representation if it doesn’t find that method.

Note

Even though print() itself uses str() for type casting, some compound data types delegate that call to repr() on their members. This happens to lists and tuples, for example.

Consider this class with both magic methods, which return alternative string representations of the same object:

class User:

def __init__(self, login, password):

self.login = login

self.password = password

def __str__(self):

return self.login

def __repr__(self):

return f"User('{self.login}', '{self.password}')"

If you print a single object of the User class, then you won’t see the password, because print(user) will call str(user), which eventually will invoke user.__str__():

user = User('jdoe', 's3cret')

print(user)

#

# jdoe

However, if you put the same user variable inside a list by wrapping it in square brackets, then the password will become clearly visible:

print([user])

#

# [User('jdoe', 's3cret')]

That’s because sequences, such as lists and tuples, implement their .__str__() method so that all of their elements are first converted with repr().

Python gives you a lot of freedom when it comes to defining your own data types if none of the built-in ones meet your needs. Some of them, such as named tuples and data classes, offer string representations that look good without requiring any work on your part. Still, for the most flexibility, you’ll have to define a class and override its magic methods described above.

Syntax in Python 2

The semantics of .__str__() and .__repr__() didn’t change since Python 2, but you must remember that strings were nothing more than glorified byte arrays back then. To convert your objects into proper Unicode, which was a separate data type, you’d have to provide yet another magic method: .__unicode__().

Here’s an example of the same User class in Python 2:

class User(object):

def __init__(self, login, password):

self.login = login

self.password = password

def __unicode__(self):

return self.login

def __str__(self):

return unicode(self).encode('utf-8')

def __repr__(self):

user = u"User('%s', '%s')" % (self.login, self.password)

return user.encode('unicode_escape')

As you can see, this implementation delegates some work to avoid duplication by calling the built-in unicode() function on itself.

Both .__str__() and .__repr__() methods must return strings, so they encode Unicode characters into specific byte representations called character sets. UTF-8 is the most widespread and safest encoding, while unicode_escape is a special constant to express funky characters, such as é, as escape sequences in plain ASCII, such as \xe9.

The print statement is looking for the magic .__str__() method in the class, so the chosen charset must correspond to the one used by the terminal. For example, default encoding in DOS and Windows is CP 852 rather than UTF-8, so running this can result in a UnicodeEncodeError or even garbled output:

user = User(u'\u043d\u0438\u043a\u0438\u0442\u0430', u's3cret')

print user

#

# đŻđŞđ║đŞĐéđ░

However, if you ran the same code on a system with UTF-8 encoding, then you’d get the proper spelling of a popular Russian name:

user = User(u'\u043d\u0438\u043a\u0438\u0442\u0430', u's3cret')

print user

#

# никита

It’s recommended to convert strings to Unicode as early as possible, for example, when you’re reading data from a file, and use it consistently everywhere in your code. At the same time, you should encode Unicode back to the chosen character set right before presenting it to the user.

It seems as if you have more control over string representation of objects in Python 2 because there’s no magic .__unicode__() method in Python 3 anymore. You may be asking yourself if it’s possible to convert an object to its byte string representation rather than a Unicode string in Python 3. It’s possible, with a special .__bytes__() method that does just that:

class User(object):

def __init__(self, login, password):

self.login = login

self.password = password

def __bytes__(self): # Python 3

return self.login.encode('utf-8')

user = User(u'\u043d\u0438\u043a\u0438\u0442\u0430', u's3cret')

bytes(user)

#

# b'\xd0\xbd\xd0\xb8\xd0\xba\xd0\xb8\xd1\x82\xd0\xb0'

Using the built-in bytes() function on an instance delegates the call to its __bytes__() method defined in the corresponding class.

:::