Functions

Functions 관련

Functions let you define re-usable pieces of code that perform specific pieces of functionality. Usually functions are able to receive some values to modify the way they work, but it's not required.

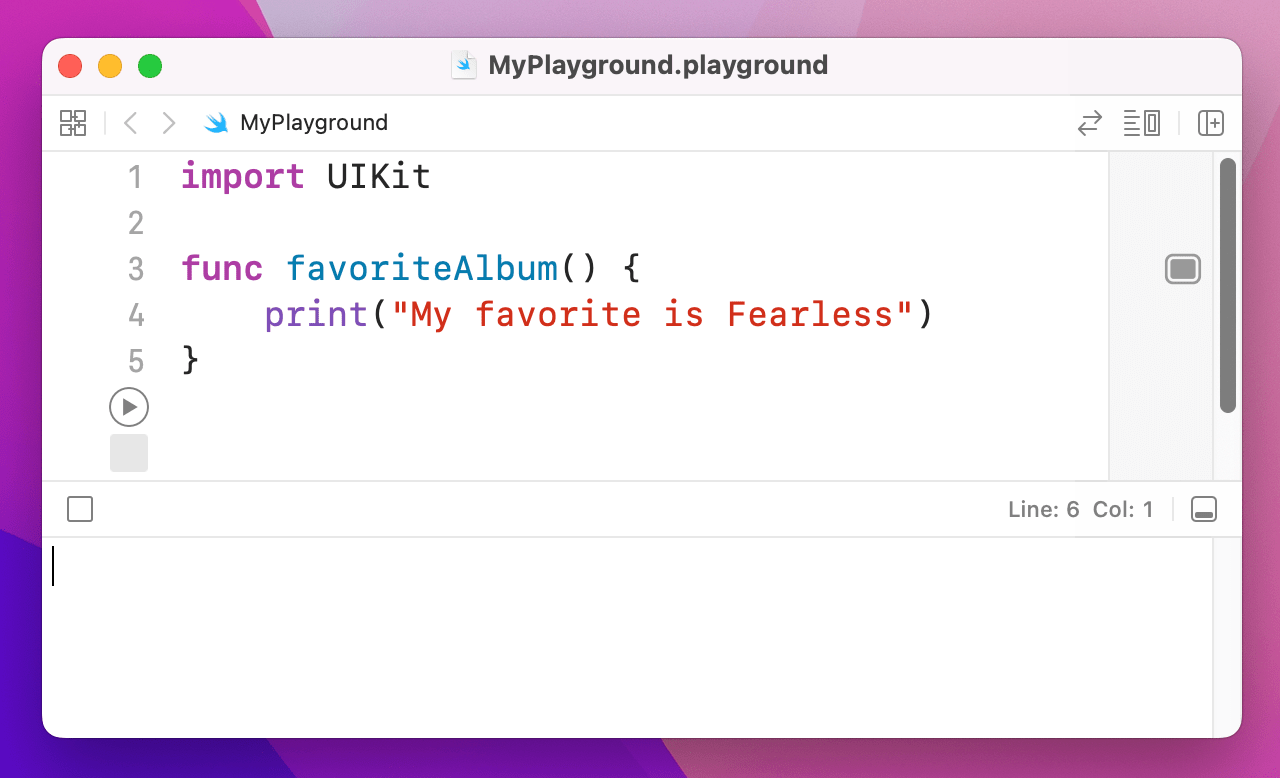

Let's start with a simple function:

func favoriteAlbum() {

print("My favorite is Fearless")

}

If you put that code into your playground, nothing will be printed. And yes, it is correct. The reason nothing is printed is that we've placed the "My favorite is Fearless" message into a function called favoriteAlbum(), and that code won't be called until we ask Swift to run the favoriteAlbum() function. To do that, add this line of code:

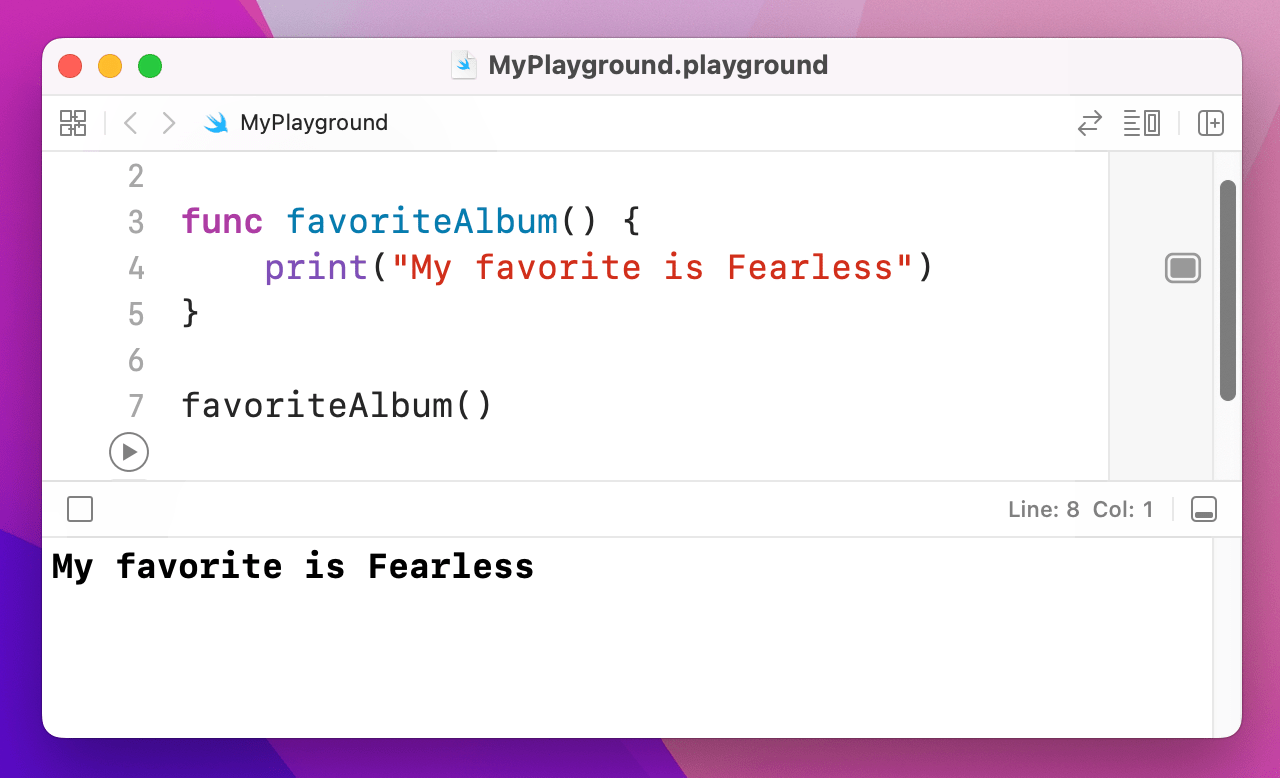

favoriteAlbum()

That runs the function (or "calls" it), so now you'll see "My favorite is Fearless" printed out.

As you can see, you define a function by writing func, then your function name, then open and close parentheses, then a block of code marked by open and close braces. You then call that function by writing its name followed by an open and close parentheses.

Of course, that's a silly example - that function does the same thing no matter what, so there's no point in it existing. But what if we wanted to print a different album each time? In that case, we could tell Swift we want our function to accept a value when it's called, then use that value inside it.

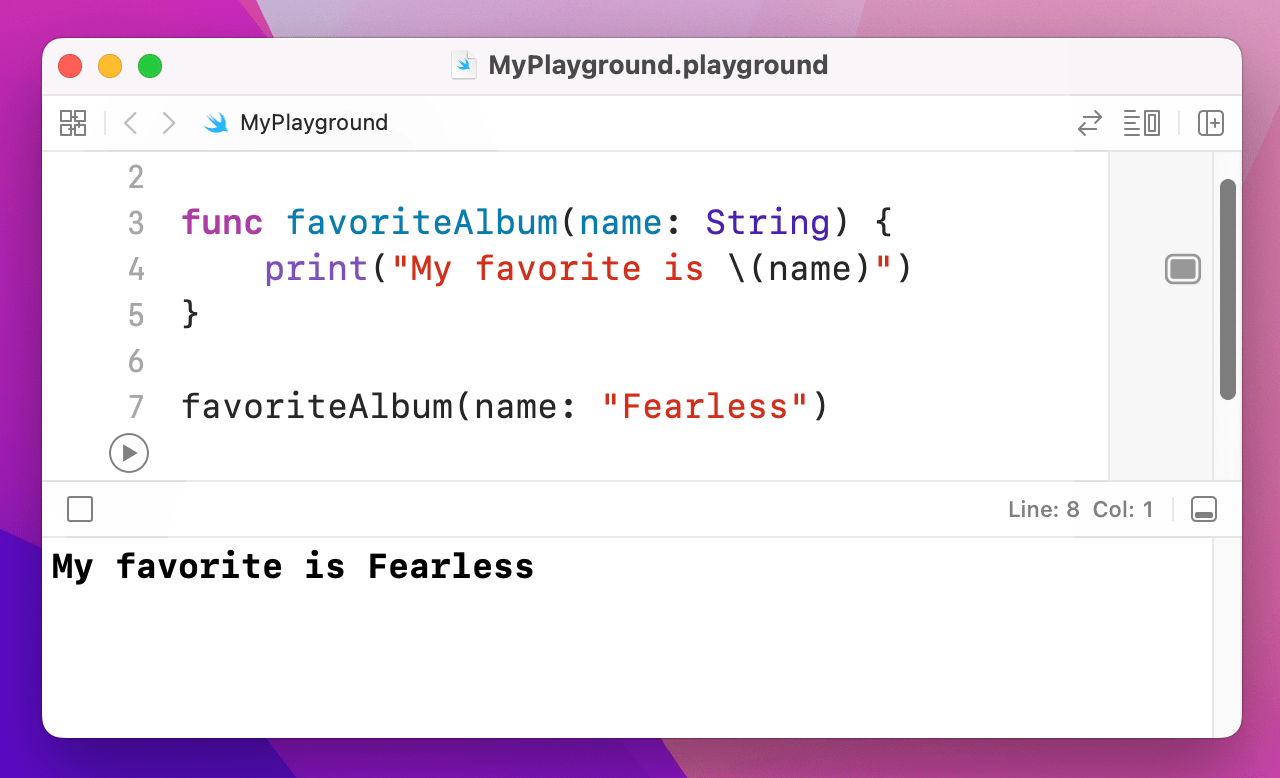

Let's do that now:

func favoriteAlbum(name: String) {

print("My favorite is \(name)")

}

That tells Swift we want the function to accept one value (called a "parameter"), named "name", that should be a string. We then use string interpolation to write that favorite album name directly into our output message. To call the function now, you’d write this:

favoriteAlbum(name: "Fearless")

name as a parameter.You might still be wondering what the point is, given that it's still just one line of code. Well, imagine we used that function in 20 different places around a big app, then your head designer comes along and tells you to change the message to "I love Fearless so much - it's my favorite!" Do you really want to find and change all 20 instances in your code? Probably not. With a function you change it once, and everything updates.

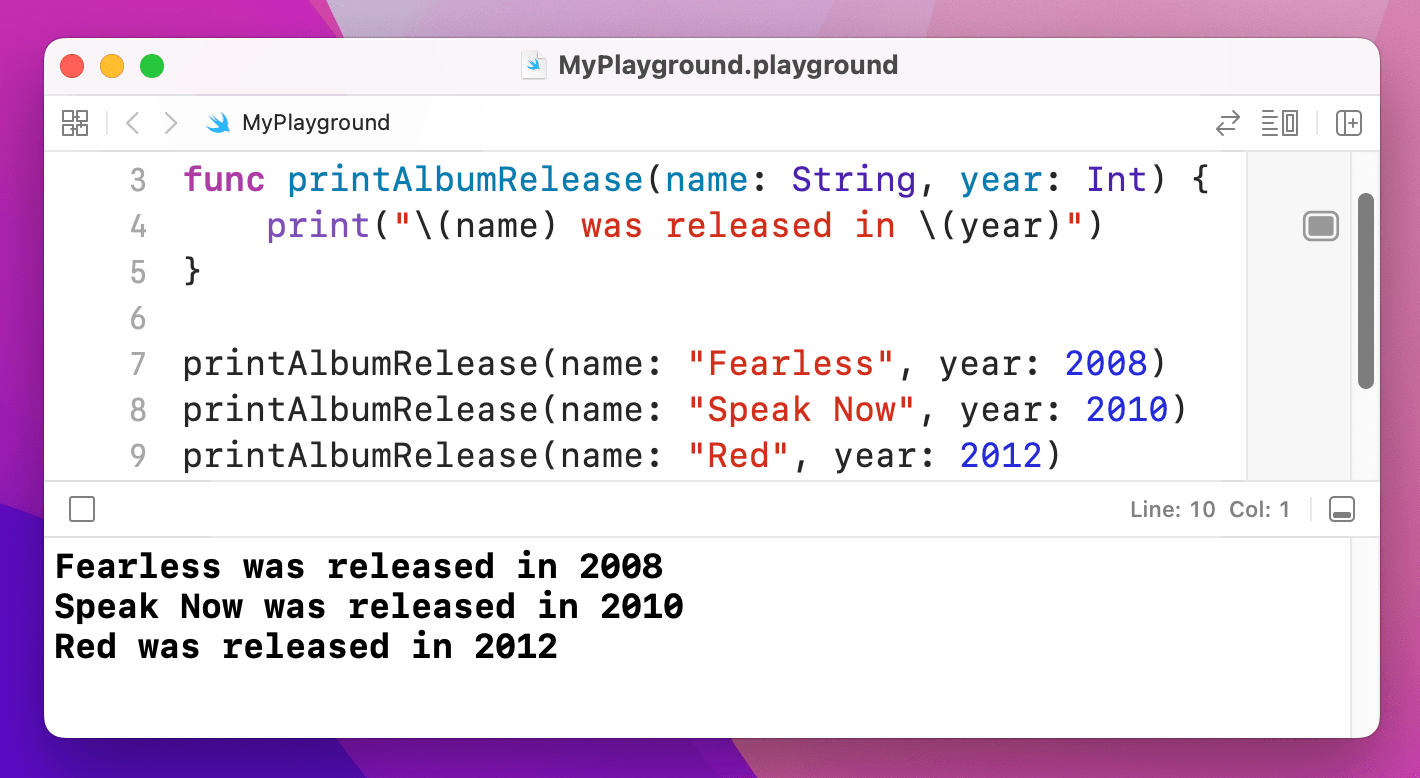

You can make your functions accept as many parameters as you want, so let's make it accept a name and a year:

func printAlbumRelease(name: String, year: Int) {

print("\(name) was released in \(year)")

}

printAlbumRelease(name: "Fearless", year: 2008)

printAlbumRelease(name: "Speak Now", year: 2010)

printAlbumRelease(name: "Red", year: 2012)

name and year parameters.These function parameter names are important, and actually form part of the function itself. Sometimes you’ll see several functions with the same name, e.g. handle(), but with different parameter names to distinguish the different actions.

External and internal parameter names

Sometimes you want parameters to be named one way when a function is called, but another way inside the function itself. This means that when you call a function it uses almost natural English, but inside the function the parameters have sensible names. This technique is employed very frequently in Swift, so it’s worth understanding now.

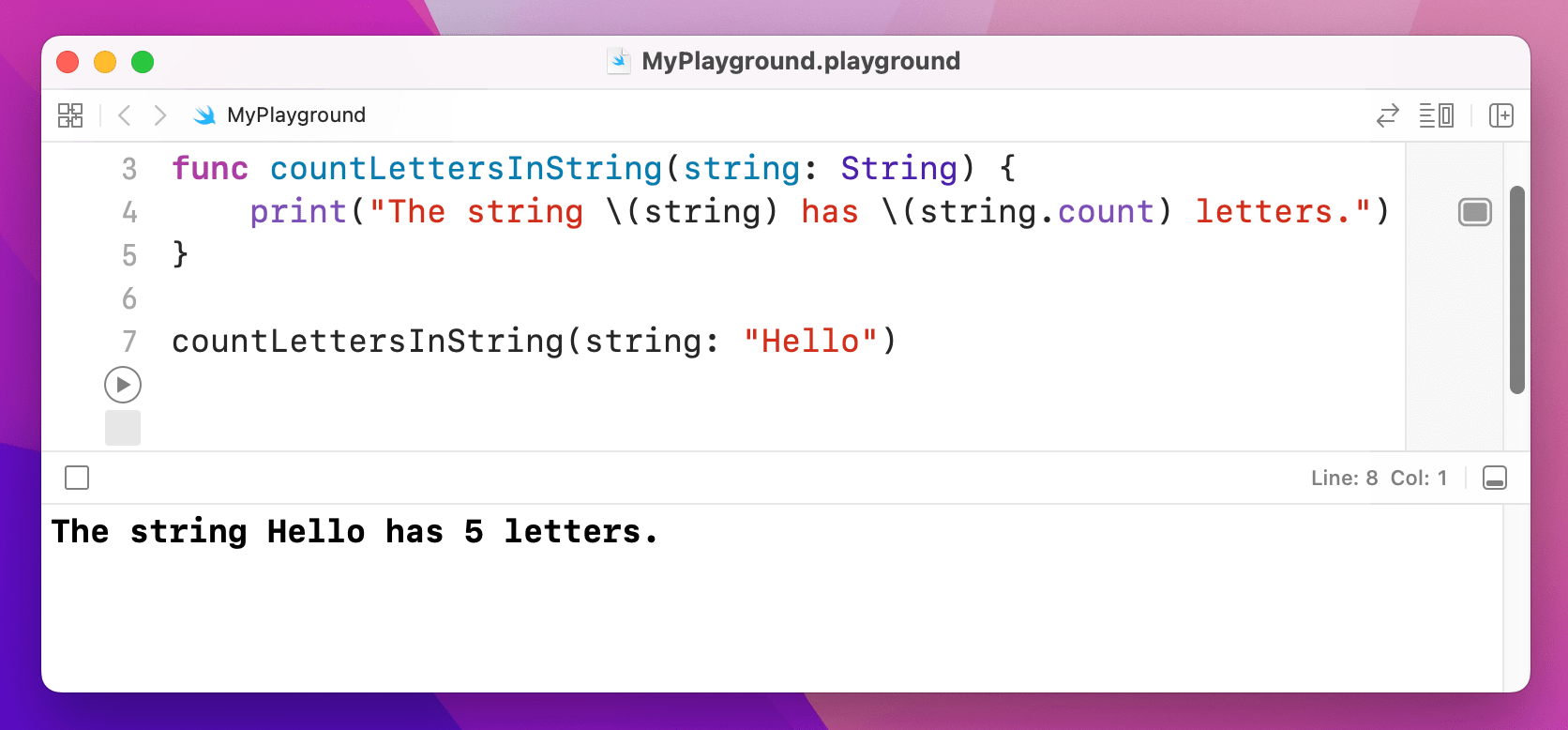

To demonstrate this, let’s write a function that prints the number of letters in a string. This is available using the count property of strings, so we could write this:

func countLettersInString(string: String) {

print("The string \(string) has \(string.count) letters.")

}

With that function in place, we could call it like this:

countLettersInString(string: "Hello")

While that certainly works, it’s a bit wordy. Plus it’s not the kind of thing you would say aloud: “count letters in string string hello”.

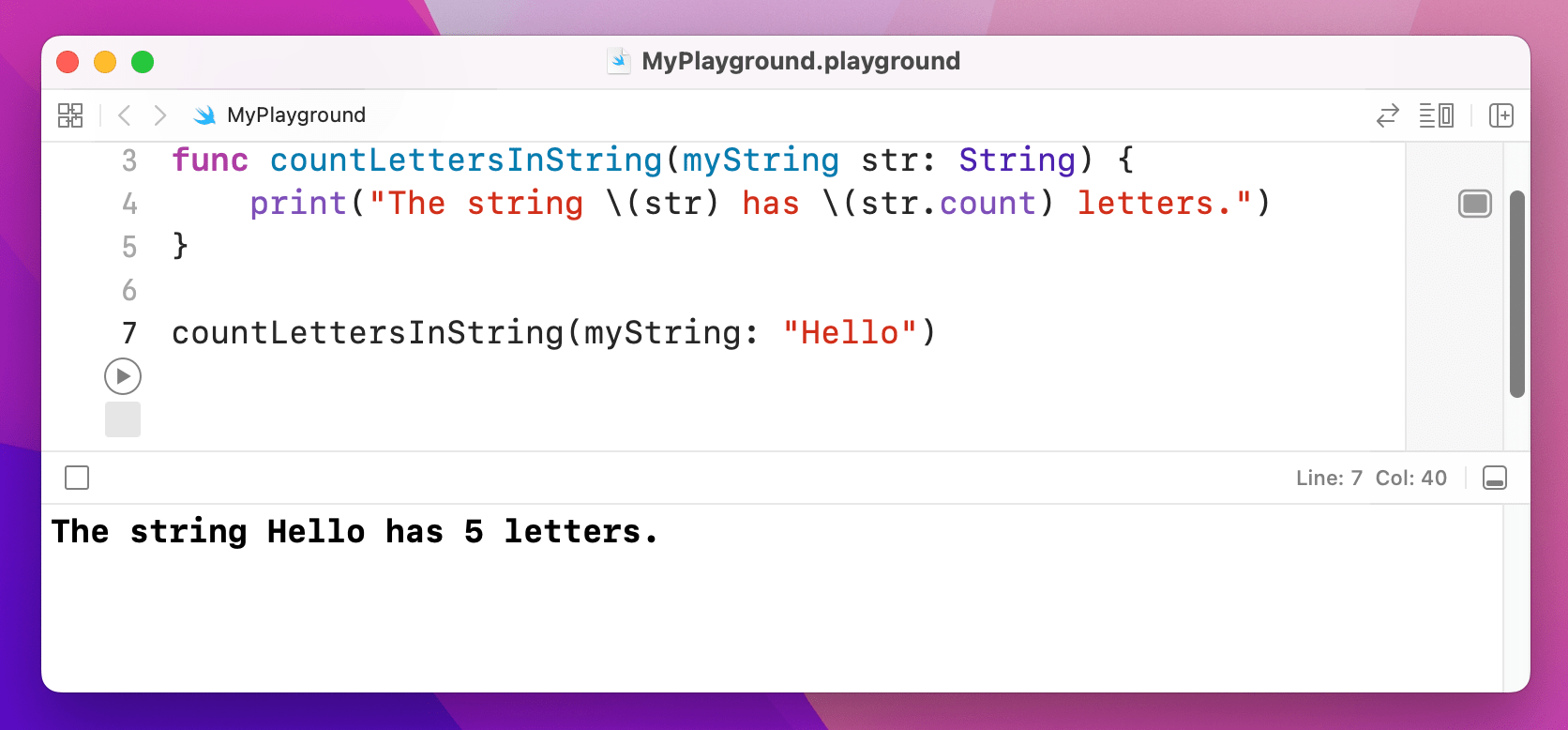

Swift’s solution is to let you specify one name for the parameter when it’s being called, and another inside the method. To use this, just write the parameter name twice - once for external, one for internal.

For example, we could name the parameter myString when it’s being called, and str inside the method, like this:

func countLettersInString(myString str: String) {

print("The string \(str) has \(str.count) letters.")

}

countLettersInString(myString: "Hello")

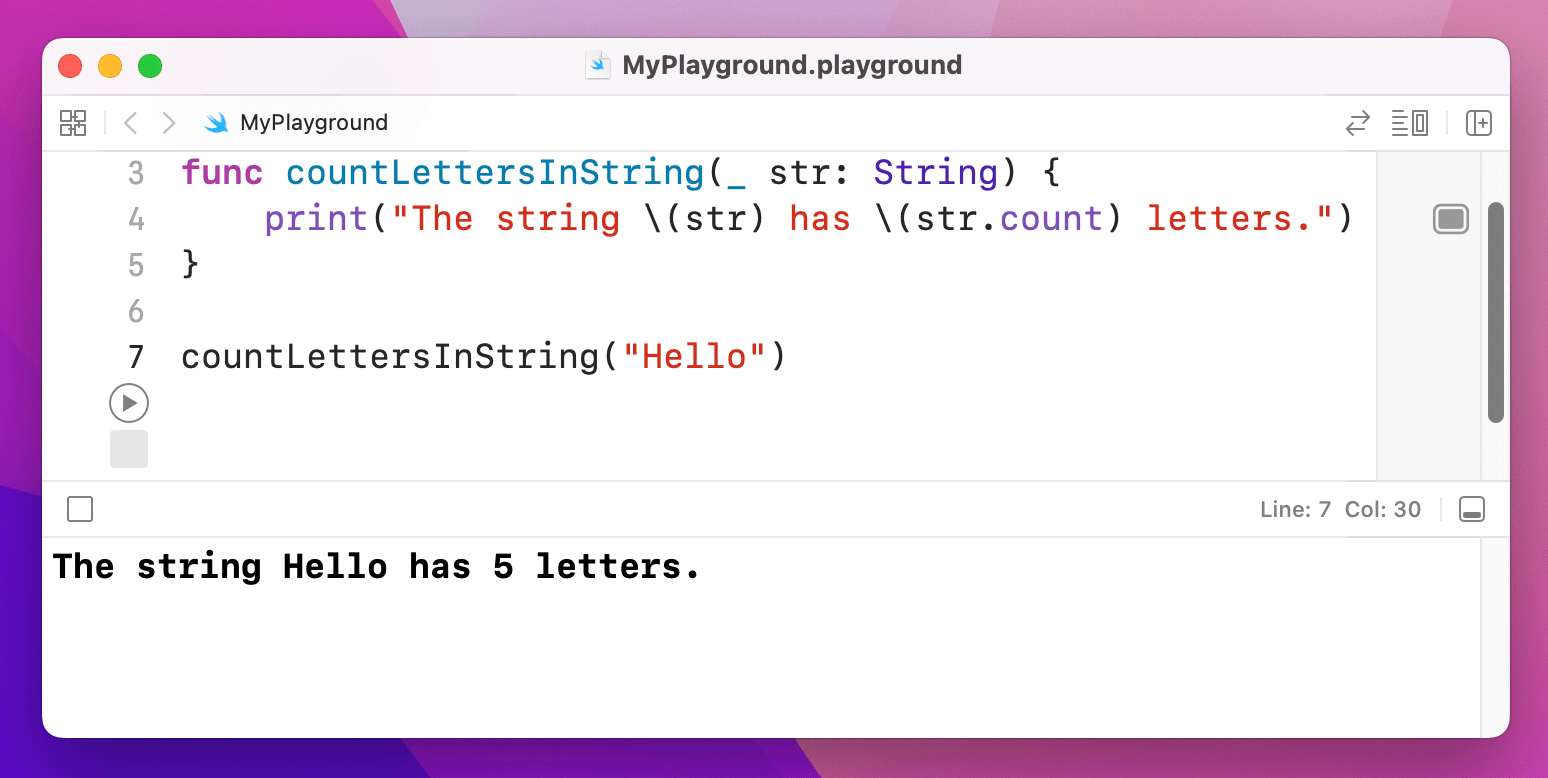

You can also specify an underscore, _, as the external parameter name, which tells Swift that it shouldn’t have any external name at all. For example:

func countLettersInString(_ str: String) {

print("The string \(str) has \(str.count) letters.")

}

countLettersInString("Hello")

As you can see, that makes the line of code read like an English sentence: “count letters in string hello”.

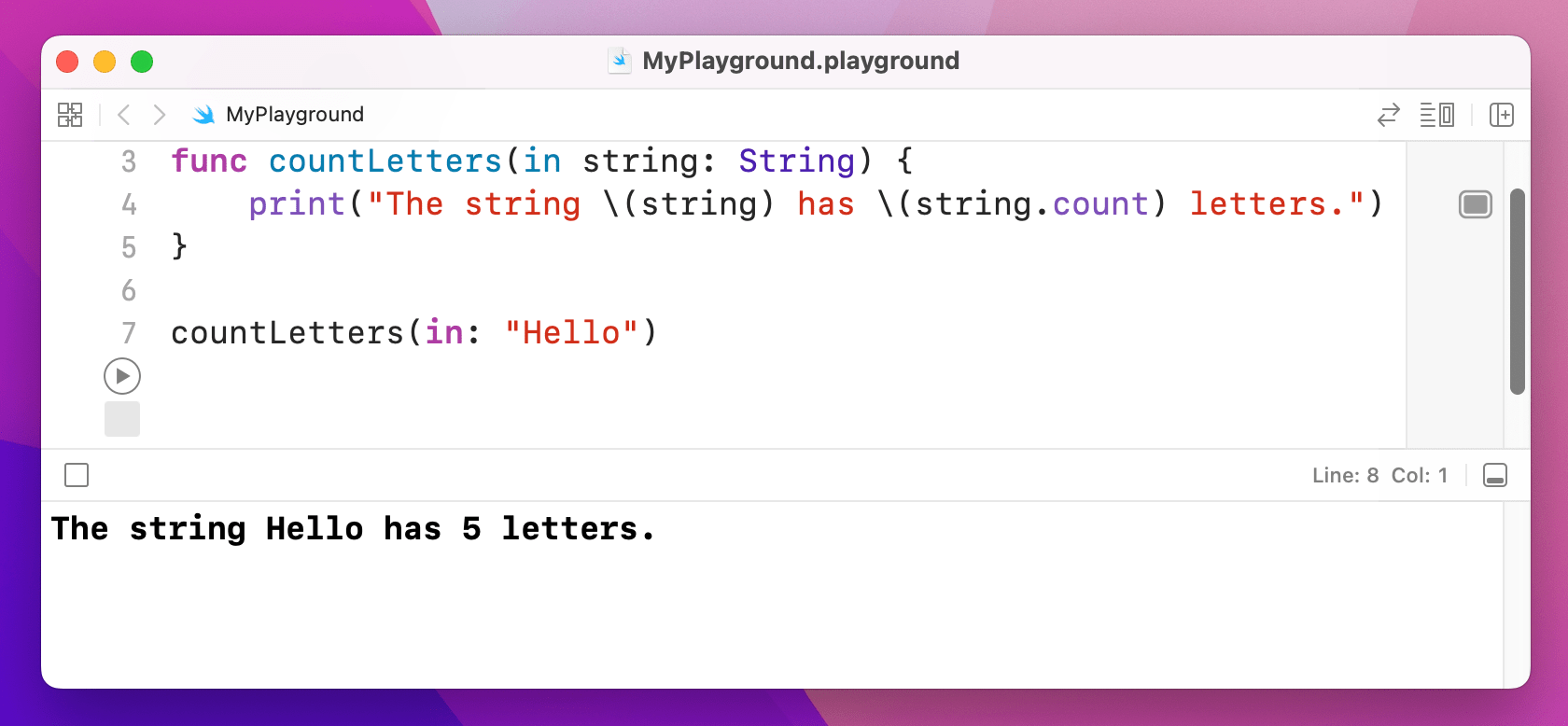

While there are many cases when using _ is the right choice, Swift programmers generally prefer to name all their parameters. And think about it: why do we need the word “String” in the function - what else would we want to count letters on?

So, what you’ll commonly see is external parameter names like “in”, “for”, and “with”, and more meaningful internal names. So, the “Swifty” way of writing this function is like so:

func countLetters(in string: String) {

print("The string \(string) has \(string.count) letters.")

}

That means you call the function with the parameter name “in”, which would be meaningless inside the function. However, inside the function the same parameter is called “string”, which is more useful. So, the function can be called like this:

countLetters(in: "Hello")

And that is truly Swifty code: “count letters in hello” reads like natural English, but the code is also clear and concise.

Return values

Swift functions can return a value by writing -> then a data type after their parameter list. Once you do this, Swift will ensure that your function will return a value no matter what, so again this is you making a promise about what your code does.

As an example, let's write a function that returns true if an album is one of Taylor Swift's, or false otherwise. This needs to accept one parameter (the name of the album to check) and will return a Boolean. Here's the code:

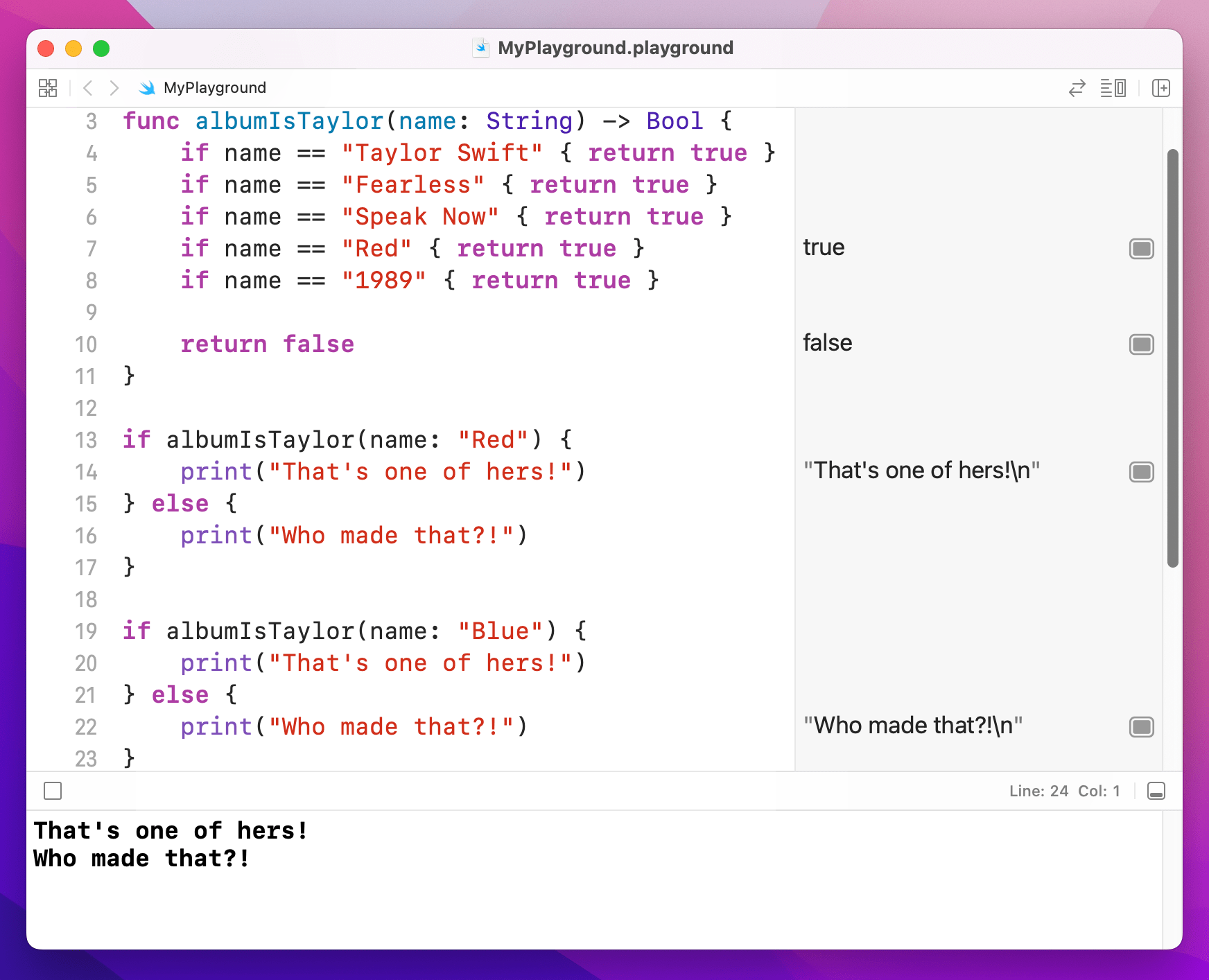

func albumIsTaylor(name: String) -> Bool {

if name == "Taylor Swift" { return true }

if name == "Fearless" { return true }

if name == "Speak Now" { return true }

if name == "Red" { return true }

if name == "1989" { return true }

return false

}

If you wanted to try your new switch/case knowledge, this function is a place where it would work well.

You can now call that by passing the album name in and acting on the result:

if albumIsTaylor(name: "Red") {

print("That's one of hers!")

} else {

print("Who made that?!")

}

if albumIsTaylor(name: "Blue") {

print("That's one of hers!")

} else {

print("Who made that?!")

}

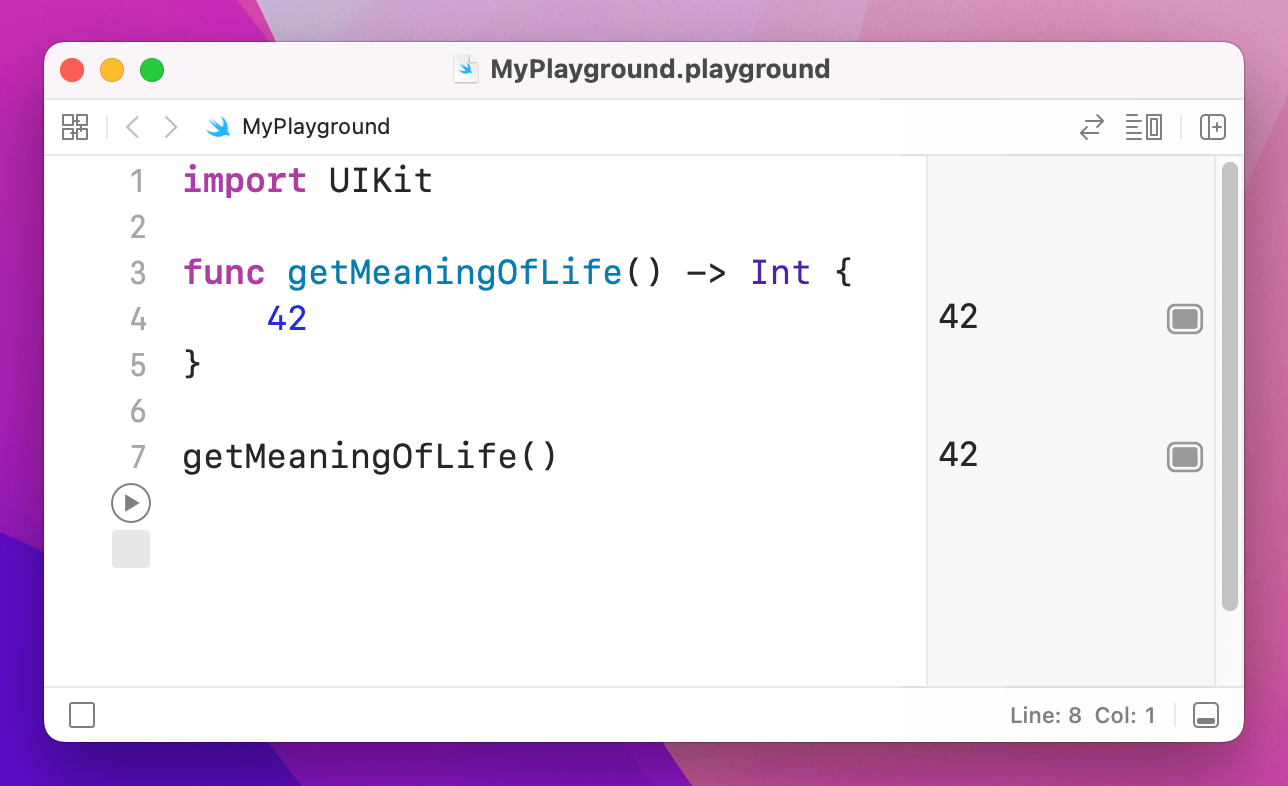

If your function returns a value and has only one line of code inside it, you can omit the return keyword entirely - Swift knows a value must be sent back, and because there is only one line that must be the one that sends back a value.

For example, we could write this:

func getMeaningOfLife() -> Int {

return 42

}

Or we could just write this:

func getMeaningOfLife() -> Int {

42

}

return.This is used very commonly in SwiftUI code.