Polymorphism and typecasting

Polymorphism and typecasting 관련

Because classes can inherit from each other (e.g. CountrySinger can inherit from Singer) it means one class is effectively a superset of another: class B has all the things A has, with a few extras. This in turn means that you can treat B as type B or as type A, depending on your needs.

Confused? Let's try some code:

class Album {

var name: String

init(name: String) {

self.name = name

}

}

class StudioAlbum: Album {

var studio: String

init(name: String, studio: String) {

self.studio = studio

super.init(name: name)

}

}

class LiveAlbum: Album {

var location: String

init(name: String, location: String) {

self.location = location

super.init(name: name)

}

}

That defines three classes: albums, studio albums and live albums, with the latter two both inheriting from Album. Because any instance of LiveAlbum is inherited from Album it can be treated just as either Album or LiveAlbum - it's both at the same time. This is called "polymorphism," but it means you can write code like this:

var taylorSwift = StudioAlbum(name: "Taylor Swift", studio: "The Castles Studios")

var fearless = StudioAlbum(name: "Speak Now", studio: "Aimeeland Studio")

var iTunesLive = LiveAlbum(name: "iTunes Live from SoHo", location: "New York")

var allAlbums: [Album] = [taylorSwift, fearless, iTunesLive]

There we create an array that holds only albums, but put inside it two studio albums and a live album. This is perfectly fine in Swift because they are all descended from the Album class, so they share the same basic behavior.

We can push this a step further to really demonstrate how polymorphism works. Let's add a getPerformance() method to all three classes:

class Album {

var name: String

init(name: String) {

self.name = name

}

func getPerformance() -> String {

return "The album \(name) sold lots"

}

}

class StudioAlbum: Album {

var studio: String

init(name: String, studio: String) {

self.studio = studio

super.init(name: name)

}

override func getPerformance() -> String {

return "The studio album \(name) sold lots"

}

}

class LiveAlbum: Album {

var location: String

init(name: String, location: String) {

self.location = location

super.init(name: name)

}

override func getPerformance() -> String {

return "The live album \(name) sold lots"

}

}

The getPerformance() method exists in the Album class, but both child classes override it. When we create an array that holds Albums, we're actually filling it with subclasses of albums: LiveAlbum and StudioAlbum. They go into the array just fine because they inherit from the Album class, but they never lose their original class. So, we could write code like this:

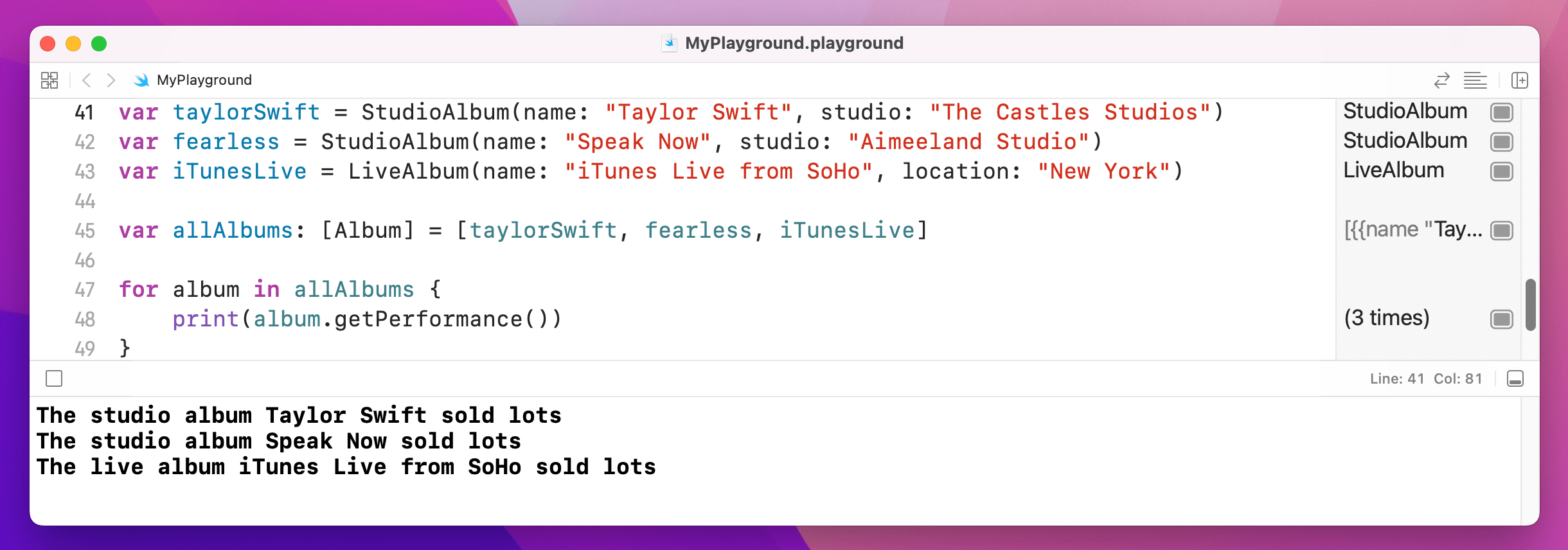

var taylorSwift = StudioAlbum(name: "Taylor Swift", studio: "The Castles Studios")

var fearless = StudioAlbum(name: "Speak Now", studio: "Aimeeland Studio")

var iTunesLive = LiveAlbum(name: "iTunes Live from SoHo", location: "New York")

var allAlbums: [Album] = [taylorSwift, fearless, iTunesLive]

for album in allAlbums {

print(album.getPerformance())

}

That will automatically use the override version of getPerformance() depending on the subclass in question. That's polymorphism in action: an object can work as its class and its parent classes, all at the same time.

Converting types with typecasting

You will often find you have an object of a certain type, but really you know it's a different type. Sadly, if Swift doesn't know what you know, it won't build your code. So, there's a solution, and it's called typecasting: converting an object of one type to another.

Chances are you're struggling to think why this might be necessary, but I can give you a very simple example:

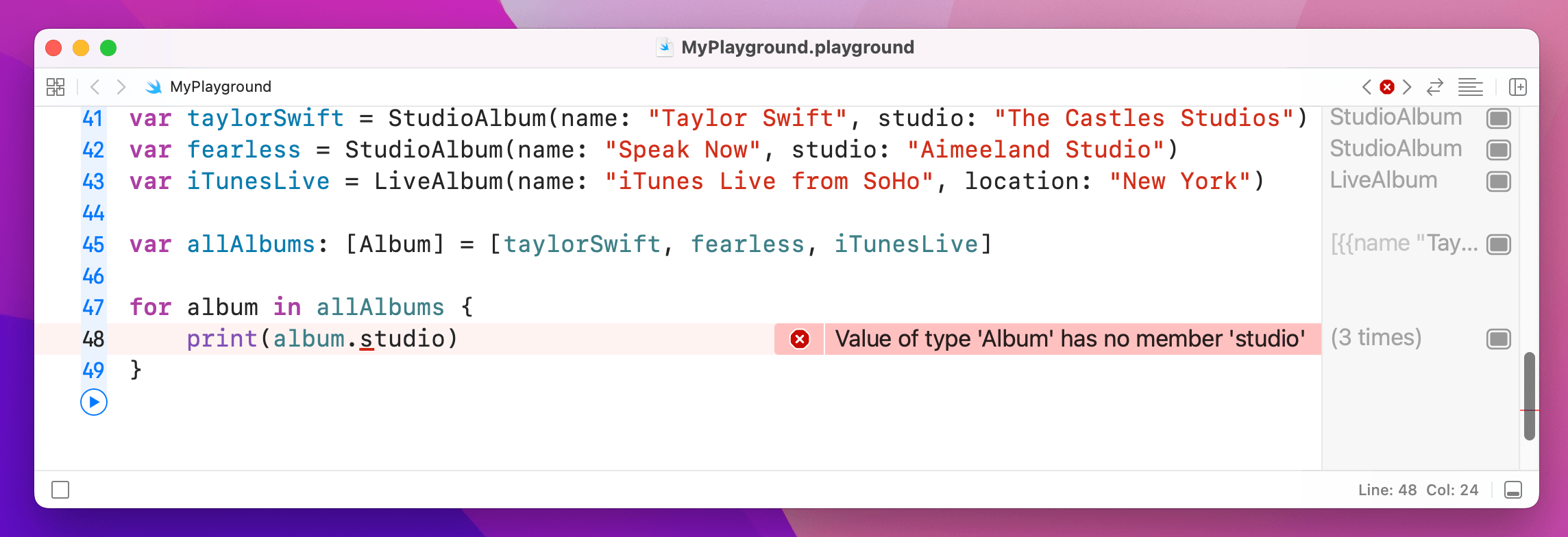

for album in allAlbums {

print(album.getPerformance())

}

That was our loop from a few minutes ago. The allAlbums array holds the type Album, but we know that really it's holding one of the subclasses: StudioAlbum or LiveAlbum. Swift doesn't know that, so if you try to write something like print(album.studio) it will refuse to build because only StudioAlbum objects have that property.

studio on Album results in an error.Typecasting in Swift comes in three forms, but most of the time you'll only meet two: as? and as!, known as optional downcasting and forced downcasting. The former means "I think this conversion might be true, but it might fail," and the second means "I know this conversion is true, and I'm happy for my app to crash if I'm wrong."

Note

when I say "conversion" I don't mean that the object literally gets transformed. Instead, it's just converting how Swift treats the object - you're telling Swift that an object it thought was type A is actually type E.

The question and exclamation marks should give you a hint of what's going on, because this is very similar to optional territory. For example, if you write this:

for album in allAlbums {

let studioAlbum = album as? StudioAlbum

}

Swift will make studioAlbum have the data type StudioAlbum?. That is, an optional studio album: the conversion might have worked, in which case you have a studio album you can work with, or it might have failed, in which case you have nil.

This is most commonly used with if let to automatically unwrap the optional result, like this:

for album in allAlbums {

print(album.getPerformance())

if let studioAlbum = album as? StudioAlbum {

print(studioAlbum.studio)

} else if let liveAlbum = album as? LiveAlbum {

print(liveAlbum.location)

}

}

That will go through every album and print its performance details, because that's common to the Album class and all its subclasses. It then checks whether it can convert the album value into a StudioAlbum, and if it can it prints out the studio name. The same thing is done for the LiveAlbum in the array.

Forced downcasting is when you're really sure an object of one type can be treated like a different type, but if you're wrong your program will just crash. Forced downcasting doesn't need to return an optional value, because you're saying the conversion is definitely going to work - if you're wrong, it means you wrote your code wrong.

To demonstrate this in a non-crashy way, let's strip out the live album so that we just have studio albums in the array:

var taylorSwift = StudioAlbum(name: "Taylor Swift", studio: "The Castles Studios")

var fearless = StudioAlbum(name: "Speak Now", studio: "Aimeeland Studio")

var allAlbums: [Album] = [taylorSwift, fearless]

for album in allAlbums {

let studioAlbum = album as! StudioAlbum

print(studioAlbum.studio)

}

That's obviously a contrived example, because if that really were your code you would just change allAlbums so that it had the data type [StudioAlbum]. Still, it shows how forced downcasting works, and the example won't crash because it makes the correct assumptions.

Swift lets you downcast as part of the array loop, which in this case would be more efficient. If you wanted to write that forced downcast at the array level, you would write this:

for album in allAlbums as! [StudioAlbum] {

print(album.studio)

}

That no longer needs to downcast every item inside the loop, because it happens when the loop begins. Again, you had better be correct that all items in the array are StudioAlbums, otherwise your code will crash.

Swift also allows optional downcasting at the array level, although it's a bit more tricksy because you need to use the nil coalescing operator to ensure there's always a value for the loop. Here's an example:

for album in allAlbums as? [LiveAlbum] ?? [LiveAlbum]() {

print(album.location)

}

What that means is, “try to convert allAlbums to be an array of LiveAlbum objects, but if that fails just create an empty array of live albums and use that instead” - i.e., do nothing.

Converting common types with initializers

Typecasting is useful when you know something that Swift doesn’t, for example when you have an object of type A that Swift thinks is actually type B. However, typecasting is useful only when those types really are what you say - you can’t force a type A into a type Z if they aren’t actually related.

For example, if you have an integer called number, you couldn’t write code like this to make it a string:

let number = 5

let text = number as! String

That is, you can’t force an integer into a string, because they are two completely different types. Instead, you need to create a new string by feeding it the integer, and Swift knows how to convert the two. The difference is subtle: this is a new value, rather than just a re-interpretation of the same value.

So, that code should be rewritten like this:

let number = 5

let text = String(number)

print(text)

This only works for some of Swift’s built-in data types: you can convert integers and floats to strings and back again, for example, but if you created two custom structs Swift can’t magically convert one to the other - you need to write that code yourself.