Kotlin Sequences - Getting Started

Kotlin Sequences - Getting Started 관련

Dealing with multiple items of a specific type is part of the daily work of, most likely, every software developer out there. A list of coffee roasters, a set of coffee origins, a mapping between coffee origins and farmers… It really depends on the use case.

You can handle this kind of data in a few ways. The most common is through the Collections API. For instance, translating the cases above, you could have something like List<Roaster>, Set<Origin> or Map<Origin, Farmer>.

While the Collections API does a good job, it might not be suited for all cases. It’s always useful to be aware of alternatives, how they work, and when they can be a better fit.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn about Kotlin’s Sequences API. Specifically, you’ll learn:

- What a sequence is and how it works.

- How to work with a sequence and its operators.

- When should you consider using sequences instead of collections.

Note

This tutorial assumes you have basic Kotlin knowledge. If not, check out Programming in Kotlin first.

Getting Started

Download the project materials by clicking the [Download Materials] button at the top or bottom of this tutorial, and open the sta**rter project.

Run the project, and you’ll notice it’s just a simple “Hello World” app. If you came here hoping to implement some cool app full of sequences everywhere, the sad truth is that you won’t even touch the app’s code.

Instead, the project exists just so you can use it to create a scratch file. When working on a project, you may want to test or draft some code before actually proceeding to a proper implementation. A scratch file lets you do just that. It has both syntax highlighting and code completion. And the best part is, it can run your code right after you write it, letting you debug it as well!

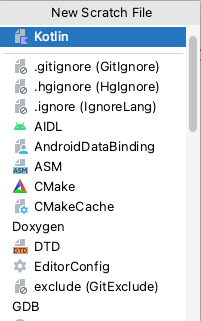

You’ll now create the scratch file where you’ll work. In Android Studio, go to [File] ▸ [New] ▸ [Scratch File].

On the little dialog that pops up, scroll until you find Kotlin, and pick it.

In your case, the position may be different.

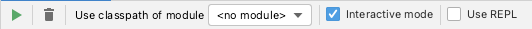

This opens your new scratch file. At the top, you have a few options to play with.

Make sure [Interactive mode] is checked. This runs any code you write after you stop typing for two seconds. The [Use classpath of module] option is pretty useful if you want to test something that uses code from a specific module. Since that’s not the case here, there’s no need to change it. Also, make sure to leave [Use REPL] unchecked, as that would run the code in Kotlin REPL, and there’s no need for that here.

Look at your project structure, and you’ll notice that the scratch file is nowhere to be seen. This is because scratch files are scoped to the IDE rather than the project. You’ll find the scratch file by switching to the Project view under Scratches and Consoles.

scratch.kts in Scratches and Consoles.This is useful if you want to share scratch files between different projects, for example. You can move it to the project’s directory, but that’s not relevant for what you’ll do in this tutorial. That said, it’s time to build some sequences!

Note

If you want to know more about scratch files, check the Jetbrains documentation about them.

Understanding Sequences

Sequences are data containers, just like collections. However, they have two main differences:

- They execute their operations lazily.

- They process elements one at a time.

You’ll learn more about element processing as you go through the tutorial. For now, you’ll dig deeper into what does it mean to execute operations in a lazy fashion.

Lazy Processing

Sequences execute their operations lazily, while collections execute them eagerly. For instance, if you apply a map to a List:

val list = listOf(1, 2, 3)

val doubleList = list.map { number -> number * 2 }

The operation will execute immediately, and doubleList will be a list of the elements from the first list multiplied by two. If you do this with sequences, however:

val originalSequence = sequenceOf(1, 2, 3)

val doubleSequence = originalSequence.map { number -> number * 2 }

While doubleSequence is a different sequence than originalSequence, it won’t have the doubled values. Instead, doubleSequence is a sequence composed by the initial originalSequence and the map operation. The operation will only be executed later, when you query doubleSequence about its result. But, before getting into how to get results from sequences, you need to know about the different ways of creating them.

Creating a Sequence

You can create sequences in a few ways. You already saw one of them above:

val sequence = sequenceOf(1, 2, 3)

The sequenceOf() function works just like the listOf() function or any other collections function of the same kind. You pass in the elements as parameters, and it outputs a sequence.

Another way of creating a sequence is by doing so from a collection:

val coffeeOriginsSequence = listOf(

"Ethiopia",

"Colombia",

"El Salvador"

).asSequence()

The asSequence() function can be called on any Iterable, which every Collection implements. It outputs a sequence with the same elements present in said Iterable.

The last sequence creation method you’ll see here is by using a generator function. Here’s an example:

val naturalNumbersSequence = generateSequence(seed = 1) { previousNumber -> previousNumber + 1 }

The generateSequence function takes a seed as the first element of the sequence and a lambda to produce the remaining elements, starting from that seed.

Unlike the Collection interface, the Sequence interface doesn’t bind any of its implementations to a size property. In other words, you can create infinite sequences, which is exactly what the code above does. The code starts at one, and goes to infinity and beyond from there, adding one to each generated value.

As you might suspect, you could get in trouble if you try to operate on this sequence. It’s infinite! What if you try to get all its elements? How will you stop?

One way is to use some kind of stopping mechanism in the generator function itself. In fact, generateSequence is programmed to stop generation when it returns null. Translating that into code, this is how to create a finite sequence:

val naturalNumbersUpToTwoHundredMillion =

generateSequence(seed = 1) { previousNumber ->

if (previousNumber < 200_000_000) { // 1

previousNumber + 1

} else {

null // 2

}

}

In this code:

- You check if the previously generated value is below 200,000,000. If so, you add one to it.

- If you reach a value equal to 200,000,000 or above, you return

null, effectively stopping the sequence generation.

Another way of stopping sequence generation is by using some of its operators, which you'll learn about in the next section.

Using Sequence Operators

Sequences have two kinds of operators:

- Intermediate operators: Operators used to build the sequence.

- Terminal operators: Operators used to execute the operations the sequence was built with.

You'll learn about intermediate operators first.

Intermediate Operators

To start understanding how operators work, write that last sequence in your scratch file:

val naturalNumbersUpToTwoHundredMillion =

generateSequence(seed = 1) { previousNumber ->

if (previousNumber < 200_000_000) {

previousNumber + 1

} else {

null

}

}

Now, build a new sequence from it by adding two intermediate operators. You'll probably recognize these, as sequences and collections have a lot of similar operators:

val firstHundredEvenNaturalNumbers = naturalNumbersUpToTwoHundredMillion

.filter { number -> number % 2 == 0 } // 1

.take(100) // 2

In this code, you:

- Filter the elements by their parity, accepting only the even ones, i.e, the ones divisible by two.

- Take the first 100 elements, discarding the rest.

As mentioned before, sequences process their operations one element at a time. In other words, filter starts by operating on the first number, 1, and then discarding it since it's not divisible by two. Then, it operates on 2, letting it proceed to take, as 2 is an even number. The operations keep going until the element operated on is 200 since, in the [1, 200_000_000] interval, 200 is the hundredth even number. At that point, neither take nor filter handle any more elements.

This might get confusing to read, so here's a visualization of what's happening:

Thanks to take(100), 200,000,000 never gets operated on, along with the all the numbers before it, from 200 onward.

As you'll notice in your scratch file, firstHundredEvenNaturalNumbers isn't actually outputting any values yet. In fact, the scratch file just shows the type:

You already know it's a sequence of Ints!

As you may suspect already, you still need a terminal operator to output the sequence's result.

Terminal Operators

Terminal operators can take many forms. Some, like toList() or toSet(), can output the sequence results as a collection. Others, like first() or sum(), output a single value.

There are a lot of terminal operators, but there's an easy way to identify them without having to dig into the implementation or documentation.

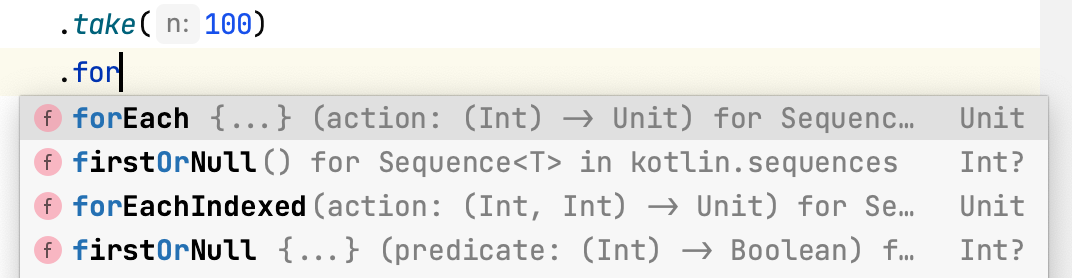

Back in your scratch file, just below take(100), start typing the map operator. As you type, Android Studio will pop up code completion. If you look at the suggestions, you'll see that map has the return type of Sequence, with R being the return type for map.

Now, delete it! Delete the map you just typed. And in its place, start typing the forEach terminal operator. When code completion pops up, notice the return type of forEach.

Unlike map, forEach doesn't return a Sequence. Which makes sense, right? It's a terminal operator, after all. So, long story short, that's how you can distinguish them at a glance:

- Intermediate operators always return a

Sequence. - Terminal operators never return a

Sequence.

You now know how to build a sequence and output its result. So, now it's time to try it out! Finish that terminal operator you were just writing by printing each element with it. In the end, you should have something like:

val firstHundredEvenNaturalNumbers = naturalNumbersUpToTwoHundredMillion

.filter { number -> number % 2 == 0 }

.take(100)

.forEach { number -> println(number) }

You'll see the result printed on the top right side of the scratch file.

Note

If you don't see anything, click the green [play] button — "run scratch file" — at the top of the file, next to the [trash can] — "clear results". Clicking the button cleans up all the output and runs the code again.

If you expand it, you'll see that it printed every even number up to 200.

Just like with collections, operator order is important in sequences. For instance, swap take with filter, like so:

val firstHundredEvenNaturalNumbers = naturalNumbersUpToTwoHundredMillion

.take(100)

.filter { number -> number % 2 == 0 }

.forEach { number -> println(number) }

Note

Before doing this change, you may want to disable [Interactive mode]. Otherwise, if you happen to cut the take(100) line — with the intent of pasting it later — the IDE will run the code from the scratch file, and it'll take a while before you get any results. This is because forEach is a terminal operator, therefore, it'll iterate two hundred million elements.

After a few seconds, the scratch file should run your code again. Expand it, and you'll see that it has printed every even number up to 100. Since take is running first, filter only gets to operate on the first 100 natural numbers, starting from one.

Now that you've played around with sequences a bit, all that's left is to address the elephant in the room: When should you use sequences?

Sequences vs. Collections

You now know how to build and use sequences. But when should you use them instead of collections? Should you use them at all?

This can be quickly answered with one of the most famous sayings in software development: It depends.

The long answer is a bit more complex. It always depends on your use case. In fact, to be really sure, you should always measure both implementations to check which one is faster. However, knowing about a few quirks surrounding sequences will also help you make a better-informed decision.

Element Operation Order

In case you have the memory of a goldfish, remember that sequences operate on each element at a time. Collections, on the other hand, execute each operation for the whole collection, building an [intermediate result] before proceeding to the next operation. So, each collection operation creates an intermediate collection with its results, where the next operation will operate on:

val list = naturalNumbersUpToTwoHundredMillion

.toList()

.filter { number -> number % 2 == 0 }

.take(100)

.forEach { number -> println(number) }

In the code above, filter would create a new list, then take would operate on that list, creating a new one of its own, and so on and so forth. That's a lot of wasted work! Especially since you're only taking 100 elements in the end. There's absolutely no need to bother with the elements after the hundredth one.

Note

It might not be wise to run this code in your scratch file. Computers aren't fond of working with such large lists. It might even stop responding! And if it doesn't, the scratch file will probably crash while building and output nothing.

Sequences effectively avoid computing intermediate results, being able to outperform collections in cases like this one. However, it's not all roses and unicorns.

Each intermediate operation added introduces some overhead. This overhead comes from the fact that each operation involves the creation of a new function object to store the transformation to be executed later. In fact, this overhead can be problematic for datasets that aren't large enough or in cases where you don't need that many operations. This overhead may even outweigh the gains from avoiding intermediate results.

To better understand where this overhead comes from, look at filter's implementation:

public fun Sequence.filter(predicate: (T) -> Boolean): Sequence {

return FilteringSequence(this, true, predicate)

}

Note

You won't be able to properly check the implementation of filter in the scratch file. If you try, the IDE will show you a decompiled .class file. For that reason, the final project has a Sequences.kt file with all the tutorial code, where you can easily check the inner workings of sequences. Or you can also check the Jetbrains source code.

That FilteringSequence is a Sequence of its own. It wraps the Sequence where you call on filter. In other words, each intermediate operator creates a new Sequence object that decorates the previous Sequence. In the end, you're left with at least as many objects as intermediate operators, all wrapped around each other.

To complicate things a bit, not all intermediate operators limit themselves to just decorating the previous sequence. Some of them need to be aware of the sequence's state.

Stateless and Stateful Operators

Intermediate operators can be:

- Stateless: They process each element independently, without needing to know about any other element.

- Stateful: They need information about other elements to process the current element.

The intermediate operators you've seen in this tutorial so far are all stateless. So, what does a stateful operator look like?

In your scratch file, just before the terminal forEach operator, add a sortedDescending() call, like so:

val firstHundredEvenNaturalNumbers = naturalNumbersUpToTwoHundredMillion

.take(100)

.filter { number -> number % 2 == 0 }

.sortedDescending() // add this call

.forEach { number -> println(number) }

As you can see from the scratch file output, you get the same list of numbers as before, but printed in reverse. For sortedDescending to be able to reverse it, it had to process each element while comparing to every other element of the sequence. But how could it do that, since sequences process one element at a time?

The answer is actually quite simple, but it'll betray your confidence in sequences. Check how sortedDescending is implemented, and you'll see that it delegates the sorting to a function called sortedWith. In turn, if you check the implementation of sortedWith, you'll see something like this:

public fun Sequence.sortedWith(comparator: Comparator): Sequence {

return object : Sequence { // 1

override fun iterator(): Iterator { // 2

val sortedList = this@sortedWith.toMutableList() // 3

sortedList.sortWith(comparator) // 4

return sortedList.iterator() // 5

}

}

}

Here's what the code is doing:

- It creates and returns an anonymous

objectthat implements theSequenceinterface. - The

objectimplements theiterator()method of theSequenceinterface. - The method converts the sequence to a

MutableList. - It then sorts the list according to the

comparator. - Finally, it returns the list's

iterator.

Wait, what?! It converts the sequence to a collection. That toMutableList is a terminal operator. This intermediate operator effectively calls a terminal operator on the sequence and then outputs a new one in the end.

So, for instance, think what will happen if you call sortedDescending on naturalNumbersUpToTwoHundredMillion before any other operator: You'll have a MutableList with two hundred million elements in memory! You can try it in your scratch file, but be warned that it'll take a while before you get any results.

It takes a while!

Running the code with two hundred million elements in memory. While not all stateful operators use a MutableList behind the curtain like sortedDescending, they all do similar tricks to have the state needed to perform their tasks. That said, these operators can have a huge negative impact on the sequence's performance, so always be mindful of when to use them, as their impact can be strong enough for collections to be a better fit.

When to Use Sequences

After all this, you should have a rough idea of the situations where sequences might come in handy. Here's a summary of the factors that might make sequences a better fit than collections:

- Working with large datasets, applying a lot of operations.

- Using intermediate operators that avoid unnecessary work — like

take, for instance. - Avoiding stateful operators.

- Avoiding terminal operators that convert the sequence to a collection — like

toList, for instance.

And again, while these might point you in the right direction, don't forget: You'll never know for sure which one fits best unless you measure!

Where to Go From Here?

You can download the completed project files by clicking the [Download Materials] button at the top or bottom of the tutorial.

In this tutorial, you learned a lot about when to use sequences versus collections, but there's still a lot to learn about the topic.

If you want to dig deeper into Sequence and operators, Kotlin's documentation is always a good place to start. Check out the documentation for Sequence and the list of operators.

To learn more about how they compare to collections, you can read Collections and sequences in Kotlin.

To measure the performance of an app, you'll find several methods and tools. You can check the user guide from Android Developers or the tutorial Android Memory Profiler: Getting Started.

I hope you've enjoyed this tutorial. If you have any questions, tips or comments, feel free to join the discussion below.