Day 19

Day 19 관련

Project 2, part one

Saint Augustine said “the world is a book, and those who do not travel read only a page.” If you’re like me, you like travel a lot, so in this project we’re going to make a small game that encourage folks to learn more about the world around them.

Yes, you read that correctly: we’re making a game. Don’t worry – you’ll still be using Swift and UIKit, and you’ll learn stacks of important skills that work just as well in apps as they do in games.

Today you have three topics to work through, and you’ll meet asset catalogs, buttons, colors, and more.

Setting up

Setting up

In this project you'll produce a game that shows some random flags to users and asks them to choose which one belongs to a particular country.

Now, when some people hear that a tutorial is about a game, they skip on. But that’s a mistake, and I’ll tell you why: the reason I mix up apps and games in Hacking with Swift is because it forces your brain to use all your skills in different ways and different contexts, which in turn helps you learn more thoroughly.

At the same time, one of the keys to learning is to use what you've learned several times over in various ways, so that your new knowledge really sinks in. The purpose of this project is to do exactly that: it's not complicated, it's about giving you the chance to use the things you just learned so that you really start to internalize it all.

That being said, there’s still lots to learn – we’ll look at asset catalogs, buttons, layers, actions, random numbers, alerts, and more.

Warning: if you skipped project 1 thinking it would all be about history or some other tedium, you were wrong. This project will be very hard if you haven't completed project 1!

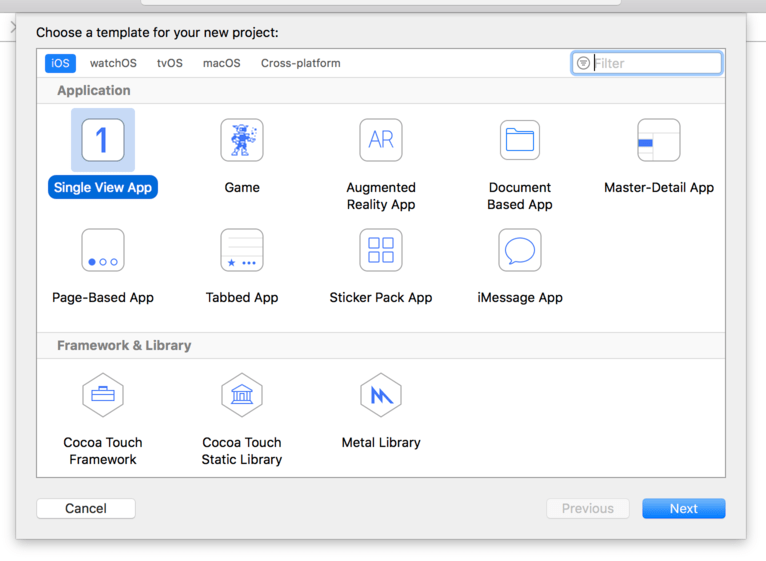

So, launch Xcode, and choose "Create a new project" from the welcome screen. Choose Single View App from the list and click Next. For Product Name enter "Project2", then make sure you have Swift selected for language. Now click Next again and you'll be asked where you want to save the project – your desktop is fine.

Designing your layout

Designing your layout

When working on my own projects, I find designing the user interface the easiest way to begin any project – it's fun, it's immediately clear whether your idea is feasible, and it also forces you to think about user journeys while you work. This project isn't complicated, but still Interface Builder is where we're going to begin.

Just as in project 1, the Single View App template gives you one UIViewController, called ViewController, and a storyboard called Main.storyboard that contains the layout for our single view controller. Choose that storyboard now to open Interface Builder, and you'll see a big, blank space ready for your genius to begin.

In our game, we're going to show users three flags, with the name of the country to guess shown in the navigation bar at the top. What navigation bar? Well, there isn't one, or at least not yet. We need to add one, just like we did with the previous project.

We covered a lot in project 1, so you’ve probably forgotten how to do this, but that’s OK: Single View App projects don't come with a navigation controller as standard, but it's trivial to add one: click inside the view controller, then go to the Editor menu and choose [Embed In] > [Navigation Controller].

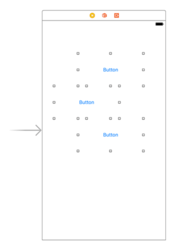

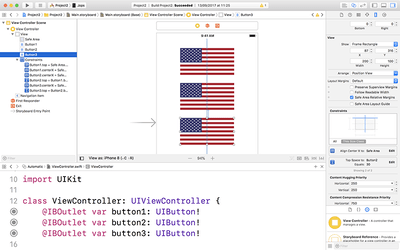

With the new navigation controller in place, scroll so you can see our empty view controller again, then use the object library to draw out three buttons onto the canvas. This is a new view type, but as you might imagine it's just a button that users can tap. Each of them should be 200 wide by 100 high. You can set these values exactly by using the size inspector in the top-right of the Xcode window.

In the early days of iOS, buttons had a white background color and rounded edges so they were visibly tappable, but these days buttons are completely flat with just some text. That's OK, though; we'll make them more interesting soon.

You can jump to the size inspector directly by pressing the keyboard shortcut Alt+Cmd+5 or by going to the View menu and choosing Utilities > Show Size Inspector. Don't worry about the X positions, but the Y positions should be 100 for the first flag, 230 for the second, and 360 for the third. This should make them more or less evenly spaced in the view controller.

In the picture below you can see the size inspector, which is the quickest and easiest way to position and size views if you know exactly where you want them.

The next step is to bring in Auto Layout so that we lay down our layout as rules that can be adapted based on whatever device the user has. The rules in this case aren't complicated, but I hope will begin to show you just how clever Auto Layout is.

We're going to create our Auto Layout rules differently from in Project 1. This is not because one way is better than another, instead just so that you can see the various possibilities and decide which one suits you best.

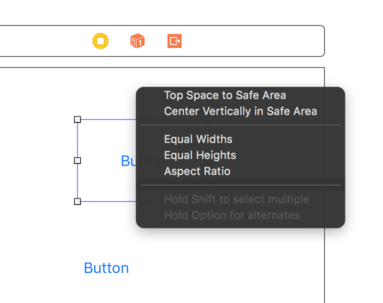

Select the top button, then Ctrl-drag from there directly upwards to just outside itself – i.e., onto the white area of the view controller. As you do this, the white area will turn blue to show that it's going to be used for Auto Layout.

When you let go of the mouse button, you'll be presented with a list of possible constraints to create. In that list are two we care about: “Top Space to Safe Area“ and "Center Horizontally in Safe Area.”

You have two options when creating multiple constraints like this: you can either select one then Ctrl-drag again and select the other, or you can hold down shift before selecting an item in the menu, and you'll be able to select more than one at a time. That is, Ctrl-drag from the button straight up to the white space in the view controller, let go of the mouse button and Ctrl so the menu appears, then hold down Shift and choose “Top Space to Safe Area“ and "Center Horizontally in Safe Area.” When that’s done, click outside the menu to close it.

That's the first flag complete, so before we go any further let's bring it to life by adding some example content so you can see how it looks.

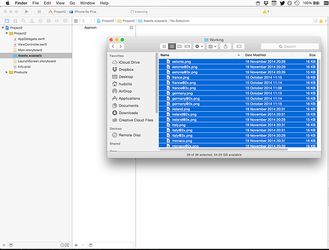

In Project 1, we added images to a project just by dragging a folder called Content into our Xcode project. That's perfectly fine and you're welcome to continue doing that for your other projects, but I want to introduce you to another option called asset catalogs. These are highly optimized ways of importing and using images in iOS projects, and are just as easy to use as a content folder.

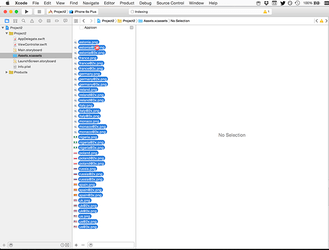

In your Xcode project, select the file called Assets.xcassets. This isn't really a file, instead it's our default Xcode asset catalog. If you haven't already downloaded the files for this project, please do so now from GitHub ( twostraws/HackingWithSwift).

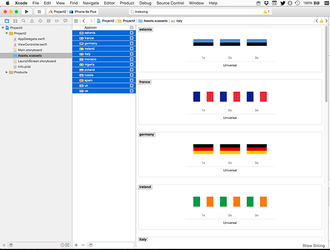

Select all 24 flag pictures from the project files, and drag them into the Xcode window to beneath where it says "AppIcon" in our asset catalog. This will create 12 new entries in the asset catalog, one for each country.

As much as I hate diversions, this one is important: iOS assets come in the sizes 2x and 3x, which are two times and three times the size of the layout you created in Interface Builder. This might seem strange, but it’s a little bit of iOS magic that takes away a huge amount of work from developers.

Early iOS devices had non-retina screens. This meant a screen resolution of 320x480 pixels, and you could place things exactly where you wanted them – you asked for 10 pixels in from the left and 10 from the top, and that was what you got.

With iPhone 4, Apple introduced retina screens that had double the number of pixels as previous screens. Rather than make you design all your interfaces twice, Apple automatically switched sizes from pixels to “points” – virtual pixels. On non-retina devices, a width of 10 points became 10 pixels, but on retina devices it became 20 pixels. This meant that everything looked the same size and shape on both devices, with a single layout.

Of course, the whole point of retina screens was that the screen had more pixels, so everything looked sharper – just resizing everything to be larger wasn’t enough. So, Apple took things a step further: if you create hello.png that was 200x100 in size, you could also include a file called hello@2x.png that was 400x200 in size – exactly double – and iOS would load the correct one. So, you write hello.png in your code, but iOS knows to look for and load hello@2x.png on retina devices.

Later, introduced retina HD screens that have a 3x resolution, and these follow the same naming convention: hello@2x.png is for retina devices, and hello@3x for retina HD devices. You still just write “hello” in your code and user interfaces, and iOS does the rest.

You might think this sounds awfully heavy – why should a retina device have to download apps that include Retina HD content that it can’t show? Fortunately, the App Store uses a technology called app thinning that automatically delivers only the content each device is capable of showing – it strips out the other assets when the app is being downloaded, so there’s no space wasted.

Cunningly, as of iOS 10 no non-retina devices are supported, so if you’re supporting only iOS 10 or later devices you only need to include the @2x and @3x images.

Now, all this is important because when we imported the images into our asset catalog they were automatically placed into 2x and 3x buckets. This is because I had named the files correctly: france@2x.png, france@3x.png, and so on. Xcode recognized these names, and arranged all the images correctly.

Once the images are imported, you can go ahead and use them either in code or in Interface Builder, just as you would do if they were loose files inside a content folder. So, go back to your storyboard, choose the first button and select the attributes inspector (Alt+Cmd+4). You'll see it has the title "Button" right now (this is in a text field directly beneath where it says "Title: Plain"), so please delete that text. Now click the arrow next to the Image dropdown menu and choose "us".

As soon as you set a picture inside the button, our constraints for the button are complete: it has a Y position because we placed a constraint, it has an X position because we're centering it horizontally, and it has a width and a height because it's reading it from the image we assigned. Go ahead and assign the US flag to the other two buttons while you're there.

To complete our Auto Layout constraints, we need to assign Auto Layout constraints for the middle and bottom buttons. Select the middle button, then Ctrl-drag to the first button – not to the view controller. Let go, and you'll see "Vertical Spacing" and "Center Horizontally.” Choose both of these. Now choose the third button and Ctrl-drag to the second button, and again choose "Vertical Spacing" and "Center Horizontally."

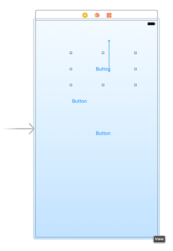

At this point, our Auto Layout is almost complete, but you'll notice that even though we chose to center the flags horizontally, they all seem to be stuck where they were placed. The reason for this is that you need to tell Interface Builder to update all the frames of your buttons to match the Auto Layout rules you just created.

This is easy enough to do: select all three image views, then go to the Editor menu and choose [Resolve Auto Layout Issues] > [Update Frames]. Again, you’ll see that option appears twice in the menu, but both do the same thing here so you can select either. This command will update the frames – the positions and sizes – of each image view so that it matches the Auto Layout constraints we set.

The last step before we're finished with Interface Builder for now is to add some outlets for our three flag buttons, so that we can reference them in code. Activate the assistant editor by pressing Alt+Cmd+Return or by going to [View] > [Assistant Editor] > [Show Assistant Editor]. Now Ctrl-drag from the first flag to your code in order to create an outlet called button1, then from the second flag to create button2, and from the third flag to create button3.

We'll come back to it later on, but for now we're done with Interface Builder. Select ViewController.swift and go back to the standard editor (that is, press Cmd+return to turn off the assistant editor) so we can get busy with some coding.

Making the basic game work: UIButton and CALayer

Making the basic game work: UIButton and CALayer

We're going to create an array of strings that will hold all the countries that will be used for our game, and at the same time we're going to create another property that will hold the player's current score – it's a game, after all!

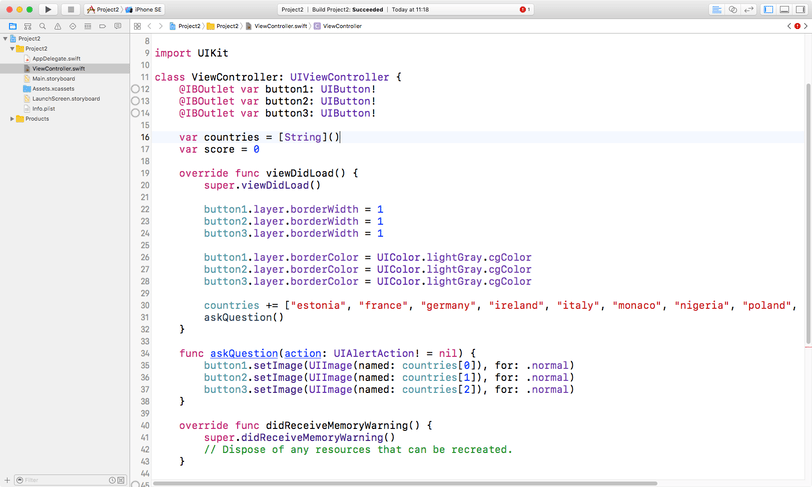

Let's start with the new properties. Add these two lines directly beneath the @IBOutlet lines you added earlier in ViewController.swift:

var countries = [String]()

var score = 0

The first line is something you saw in project 1: it creates a new property called countries that will hold a new array of strings. The second one creates a new property called score that is set to 0. As you’ve seen previously, Swift’s type inference works wonders here – it figures out what data type a variable or constant should be based on what we put into it.

We're going to be putting all this into practice over the next few minutes. First, let's fill our countries array with the flags we have, so add this code inside the viewDidLoad() method:

countries.append("estonia")

countries.append("france")

countries.append("germany")

countries.append("ireland")

countries.append("italy")

countries.append("monaco")

countries.append("nigeria")

countries.append("poland")

countries.append("russia")

countries.append("spain")

countries.append("uk")

countries.append("us")

This is identical to the code you saw in project 1, so there's nothing to learn here. If you recall your Swift introduction, you’ll know there's a more efficient way of doing this, which is to create it all on one line. To do that, you would write:

countries += ["estonia", "france", "germany", "ireland", "italy", "monaco", "nigeria", "poland", "russia", "spain", "uk", "us"]

The next step is to write a method that shows three random flag images on the screen. Buttons have a setImage() method that lets us control what picture is shown inside and when, so we can use that with UIImage to display our flags.

Add this new method underneath viewDidLoad():

func askQuestion() {

button1.setImage(UIImage(named: countries[0]), for: .normal)

button2.setImage(UIImage(named: countries[1]), for: .normal)

button3.setImage(UIImage(named: countries[2]), for: .normal)

}

The first line is easy enough: we're declaring a new method called askQuestion(), and it takes no parameters. The next three use UIImage(named:) and read from an array by position, both of which we used in project 1, so that bit isn't new either. However, the rest of those lines is new, and shows off two things:

button1.setImage()assigns aUIImageto the button. We have the US flag in there right now, but this will change it whenaskQuestion()is called.for: .normalThesetImage()method takes a second parameter that describes which state of the button should be changed. We're specifying.normal, which means "the standard state of the button."

That .normal parameter looks like an enum, but it’s actually a static property of a struct called UIControlState. In Objective-C – the language UIKit was written in – it’s an enum, but in Swift it gets mapped to a struct that just happens to be used like an enum, so if you want to be technically correct it’s not a true enum in Swift. At this point in your Swift career there is no difference, but let’s face it: “technically correct” is the best kind of correct.

Now that we have the countries all set up and a method that displays flags, all we need to do is add one more line just before the end of viewDidLoad() to make it all spring to life:

askQuestion()

At this point the game is in a fit state to run, so let’s give it a try.

First, select the iPhone XR simulator by going to the Product menu and choosing [Destination] > [iPhone XR]. Now press Cmd+R now to launch the Simulator and give it a try.

You'll immediately notice two problems

- We're showing the Estonian and French flags, both of which have white in them so it's hard to tell whether they are flags or just blocks of color

- The "game" isn't much fun, because it's always the same three flags!

The second problem is going to have to wait a few minutes, but we can fix the first problem now. One of the many powerful things about views in iOS is that they are backed by what's called a CALayer, which is a Core Animation data type responsible for managing the way your view looks.

Conceptually, CALayer sits beneath all your UIViews (that's the parent of UIButton, UITableView, and so on), so it's like an exposed underbelly giving you lots of options for modifying the appearance of views, as long as you don't mind dealing with a little more complexity. We're going to use one of these appearance options now: borderWidth.

The Estonian flag has a white stripe at the bottom, and because our view controller has a white background that whole stripe is invisible. We can fix that by giving the layer of our buttons a borderWidth of 1, which will draw a one point black line around them. Put these three lines in viewDidLoad() directly before it calls askQuestion():

button1.layer.borderWidth = 1

button2.layer.borderWidth = 1

button3.layer.borderWidth = 1

Remember how points and pixels are different things? In this case, our border will be 1 pixel on non-retina devices, 2 pixels on retina devices, and 3 on retina HD devices. Thanks to the automatic point-to-pixel multiplication, this border will visually appear to have more or less the same thickness on all devices.

By default, the border of CALayer is black, but you can change that if you want by using the UIColor data type. I said that CALayer brings with it a little more complexity, and here's where it starts to be visible: CALayer sits at a lower technical level than UIButton, which means it doesn't understand what a UIColor is. UIButton knows what a UIColor is because they are both at the same technical level, but CALayer is below UIButton, so UIColor is a mystery.

Don't despair, though: CALayer has its own way of setting colors called CGColor, which comes from Apple's Core Graphics framework. This, like CALayer, is at a lower level than UIButton, so the two can talk happily – again, as long as you're happy with the extra complexity.

Even better, UIColor (which sits above CGColor) is able to convert to and from CGColor easily, which means you don't need to worry about the complexity – hurray!

So, let's put all that together into some code that changes the border color using UIColor and CGColor together. Put these three just below the three borderWidth lines in viewDidLoad():

button1.layer.borderColor = UIColor.lightGray.cgColor

button2.layer.borderColor = UIColor.lightGray.cgColor

button3.layer.borderColor = UIColor.lightGray.cgColor

As you can see, UIColor has a property called lightGray that returns (shock!) a UIColor instance that represents a light gray color. But we can't put a UIColor into the borderColor property because it belongs to a CALayer, which doesn't understand what a UIColor is. So, we add .cgColor to the end of the UIColor to have it automagically converted to a CGColor. Perfect.

If lightGray doesn't interest you, you can create your own color like this:

UIColor(red: 1.0, green: 0.6, blue: 0.2, alpha: 1.0).cgColor

You need to specify four values: red, green, blue and alpha, each of which should range from 0 (none of that color) to 1.0 (all of that color). The code above generates an orange color, then converts it to a CGColor so it can be assigned to a CALayer's borderColor property.

That's enough with the styling, I think – if you run the app now it should look better.